Black history at the United Nations

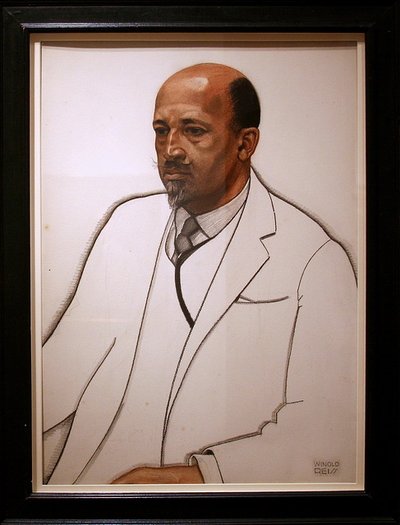

“It is not Russia that threatens the United States so much as Mississippi…[I]nternal injustice done to one’s brothers is far more dangerous than the aggression of strangers from abroad.” — W.E.B. DuBois

On October 23, 1947, the NAACP sent to the UN a document titled “An Appeal to the World,” in which the NAACP asked the UN to redress human rights violations the United States committed against its African-American citizens. W.E.B. Du Bois, who drafted the NAACP petition with the assistance of Earl B. Dickerson (J.D. ’20), William Robert Ming, Jr. (J.D. ’33), and other leading lawyers and scholars, intended to focus attention on the U.S.’s systematic denial of human rights to its Black citizens. The lawyers and scholars gathered and presented in the petition facts about lynching, segregation, and the gross inequalities in education, housing, health care, and voting rights.

“At first [the American Negro] was driven from the polls in the South by mobs and violence; and then he was openly cheated; finally by a ‘Gentlemen’s agreement’ with the North, that Negro was disfranchised in the South by a series of laws, methods of administration, court decisions, and general public policy, so that today, three-fourths of the Negro population of the nation is deprived of the right to vote by open and declared policy.”

In addition, the petition argued that the racial discrimination in American made it not a good location for the United Nations:

“Most people of the world are more or less colored in skin; their presence at the meetings of the United Nations as participants and as visitors, renders them always liable to insult and to discrimination; because they may be mistaken for Americans of Negro descent.

Not very long ago the nephew of the ruler of a neighboring American state, was killed by policemen in Florida because he was mistaken for a Negro and thought to be demanding rights which a Negro in Florida is not legally permitted to demand. Again and more recently in Illinois, the personal physician of Mahatma Ghandi, one of the great men of the world and an ardent supporter of the United Nations, was with his friends refused food in a restaurant, again because they were mistaken for Negroes. In a third case, a great insurance society in the United States in its development of a residential area, which would serve for housing the employees of the United Nations, is insisting in reserving the right to discriminate against the persons received as residents for reasons of race and color.”

Reactions to the petition were varied, but strong. Eleanor Roosevelt, a driving force behind the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, notably reacted adversely to the petition. From Cold War Civil Rights (Dudziak, at 45):

“Although Eleanor Roosevelt, a member of board of directors of the NAACP, was also a member of the American delegation to the United Nations, she refused to introduce the NAACP petition in the United Nations out of concern that it woud harm the international reputation of the United States. According to Du Bois, the American delegation had ‘refused to bring the curtailment of our civil rights to the attention of th General Assembly [and] refused willingly to allow any other nation to bring this matter up. If any should, Mr. [sic] Roosevelt has declared that she would probably resign from the United Nations delegation.’ The Soviet Union, however, proposed that the NAACP’s charges be investigated. On December 4, 1947, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights rejected that proposal, and the United Nations took no action on the petition.”

W.E.B. Du Bois conceived of the idea of the NAACP petition from an earlier petition by the National Negro Congress submitted to the UN on June 6, 1946. Mr. Du Bois participated in a later petition submitted to the UN by the Civil Rights Congress called “We Charge Genocide” (1952). Sources for the text of these petitions and works about them are listed below.

Bibliography

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. An Appeal to the World! A Statement on the Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of Citizens of Negro Descent in the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress (New York: NAACP, 1947)(prepared under the editorial supervision of W.E. Burghardt Du Bois, with contributions by Earl B. Dickerson, Milton R. Konvitz, William R. (Robert) Ming, Jr., Leslie S. Perry, and Rayford W. Logan). Regenstein, Bookstacks. JK1924.N3. [excerpts online via the Library of Congress]

We Charge Genocide; The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the United States Government Against the Negro People (U.S. Civil Rights Congress, New York, 1952). Regenstein, Bookstacks. E185.61.C6 1970 [online via Hathi Trust]

Carol Anderson, Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944-1955 (Cambridge University Press, 2003). D’Angelo Law Library, Bookstacks. E185.61.A543 2003 c.2

Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2000 & 2011). D’Angelo Law Library, Bookstacks. E185.61.D85 2000 c.1

Langston Hughes (with Christopher C. De Santis ed.), Fight for Freedom and Other Writings on Civil Rights 114-116 (University of Missouri Press, 2001)(The Collected Works of Langston Hughes, v.10). [ebrary eBook]

William L. Krenn (ed.), The African American Voice in U.S. Foreign Policy Since World War II (v.5 of Race and U.S. Foreign Policy from the Colonial Period to the Present: A Collection of Essays)(Garland, 1998). D’Angelo Law Library, Bookstacks. E744.R168 1998 v.5

David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. DuBois (v. 2, The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963) (H. Holt/MacMillan, 2001). D’Angelo Law Library, Bookstacks. E185.9.D73L480 1993 v.2

Jonathan Rosenberg, How Far the Promised Land?: World Affairs and the American Civil Rights Movement from the First World War to Vietnam (Princeton University Press, 2006). Regenstein, Bookstacks. E185.61.R8155 2006

Patricia Sullivan, Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement 323 (New Press, 2009). Regenstein, Bookstacks. E185.5.N276 S85 2009 [ebrary eBook]

Sondra K. Wilson, In Search of Democracy: The NAACP Writings of James Weldon Johnson, Walter White, and Roy Wilkins (1920-1977) 197 (Oxford University Press, 1999). Regenstein, Bookstacks. E185.61.I513 1999 [ebrary eBook]

Walter Wilson (ed.), The Selected Writings of W.E.B. Du Bois (New American Library, 1970).

Howard Winant, The World Is a Ghetto: Race and Democracy Since World War II (Basic Books, 2001). Regenstein, Bookstacks. HT1521.W56 2001