Innovation on a grand scale: Revisiting Regenstein Library at 50

The opening of the Joseph Regenstein Library in 1970 was a transformative moment in the academic history of the University of Chicago. Consolidating more than 1.6 million volumes into stacks spaces arranged across seven expansive floors, the massive new building brought together the Library’s general humanities and social science collections with holdings from twelve departmental libraries previously housed in separate buildings across the campus.

The dream of a great central library for the University of Chicago had been pursued by presidents, trustees, donors, and library directors for nearly 50 years. After Harper Memorial Library opened in 1912, there was hope at first that its Gothic-accented public spaces and underground stacks could meet the needs of the growing University for decades to come. But Harper’s study and stack spaces were soon exhausted, leading the University to continue to expand a network of departmental libraries within new buildings being constructed on campus through the 1920s and into the 1930s.

By the late 1920s the Library had completed the monumental task of cataloging all of its holdings in the newly developed Library of Congress classification system. Still, locating and retrieving books from scattered departmental libraries in different buildings was becoming an increasingly onerous task for scholars and students pursuing research in newly expanding interdisciplinary fields.

Planning, funding, and designing a new library

During the Depression and World War II, nothing could be done to address these challenges. But the appointment of Herman Fussler as Library Director in 1948 brought new impetus to the Library and a fresh vision for addressing the University’s unmet library needs. Through the late 1940s and 1950s, under Fussler’s direction, various proposals were reviewed to expand Harper Library or construct an entirely new library building. Unfortunately, none of these was able to attract the necessary funding, and each fell short of providing capacity to house the significant growth in book collections that was now being projected.

Planning quickened decisively in 1962 when the University Board of Trustees authorized development of a new research library to house collections in the humanities and social sciences, with separate libraries projected for law and the sciences. Edward H. Levi, who had been appointed the University’s first Provost, took the key role in identifying donors in the next stage of development. In 1964, through the generosity of Florence Lowden Miller, granddaughter of Chicago railroad car manufacturer George Pullman, the Harriet Pullman Schermerhorn Charitable Trust provided $500,000 to fund the architectural planning of the new main library building.

In 1965, Chicago philanthropist Helen Ascher Regenstein and the Regenstein family agreed to make the decisive major gift needed for construction, providing $10 million from the Joseph and Helen Regenstein Foundation. The Regenstein gift was supplemented by a federal higher education grant and donations from other sources secured by the University. At the request of the Regenstein family, the University’s new research center for humanities and social science collections was named in honor of Mrs. Regenstein’s late husband, Chicago industrialist and manufacturer Joseph Regenstein.

To serve as the site of the new building, the University selected historic Stagg Field, the largest open area available on campus. Once home to legendary Big Ten football contests and Enrico Fermi’s pioneering Manhattan Project nuclear pile experiment during World War II, Stagg Field and its old turreted walls were to be systematically demolished as the massive reinforced concrete frame of the new library rose behind them.

The conceptual design of Regenstein Library was influenced by the Brutalist style in favor in the mid-1960s. Architect Walter Netsch of the Chicago firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, however, avoided the rough poured concrete used as a facing material on other Brutalist buildings. Netsch instead sheathed the exterior of Regenstein Library in panels of limestone, each elegantly scored with deep sets of vertical grooves that lightened the visual mass and, in a suggestion of Gothic form, lifted the visitor’s eyes upward.

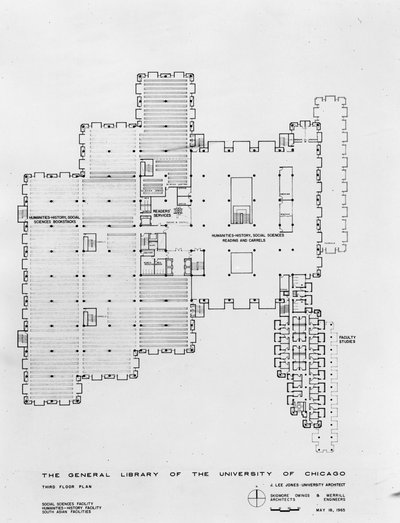

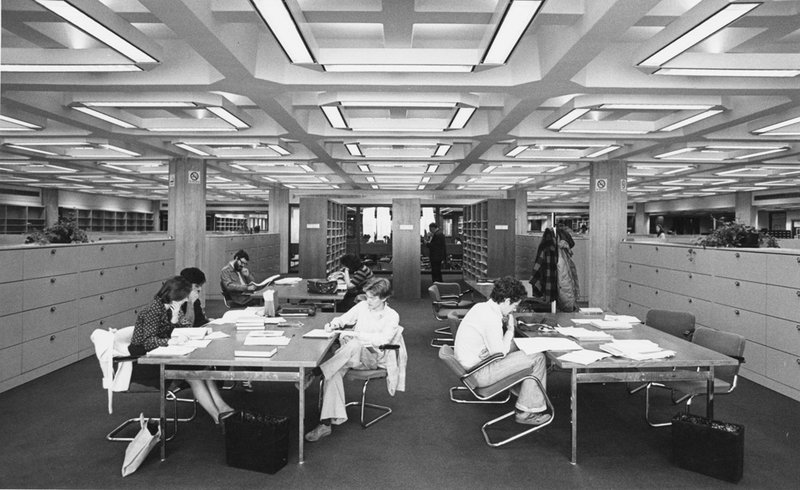

As impressive as Regenstein Library was on the exterior, its true proportions were fully apparent only inside the massive building. Constructed in staggered parallel segments running north-south, the library took its form from a rectilinear grid of regularly spaced load-bearing columns. Seven huge floors, five above ground and two below, offered 575,000 square feet of floor space, the equivalent of 13.2 acres. Architects projected a stacks capacity of 2.9 million books, reading room and study room seating for 2,400 researchers, and space for 260 faculty studies. Also within the building, the University of Chicago Graduate Library School was given the dedicated instructional and office space it had long lacked. On a campus where most faculty and students worked in confined older quarters, the library’s spacious new features promised fresh research and learning opportunities on a dramatic scale.

While Walter Netsch commanded the development of the architectural design, the organizational program of Regenstein Library was being decisively shaped by the bibliographic vision of Director Herman Fussler. In accordance with Fussler’s plan, each floor of the building was subdivided into repeating zones defined by use – bookstacks to the west, reading rooms and study spaces in the center, and private faculty studies and the Graduate Library School on the east. The Cartesian logic of the main Regenstein floor layout was interrupted only by an angular staircase linking the second and third floors and by boldly colored carpeting - red, gold, blue, green – accenting and visually differentiating each floor.

Herman Fussler’s shelving arrangement for the book collections followed an equally rational plan. Monographs and serials arriving from Harper and departmental libraries across campus were intershelved into sequential call number order, creating the largest single unified book collection in the Library’s history. Disciplines and related sub-disciplines were assigned contiguous stack space on individual floors, with reference materials related to those fields arranged on shelves for easy access in that floor’s adjacent reading room.

In addition to the general subject collections housed in the main stacks, Regenstein Library was also designed to accommodate specialized materials requiring separate housing and curation. The Department of Special Collections was housed in a suite of spaces on the first floor of Regenstein, with staff offices and stack spaces on two floors below. A long corridor leading to the Special Collections entrance was lined with two dozen vertical display cases, one of the largest purpose-built exhibition spaces of its kind in any American university library of the time. On the fifth floor of Regenstein, a separate suite of spaces formed the East Asian Library, which consolidated resources, reading room, and staff spaces for research in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean language materials. In acknowledgment of the departmental libraries moved to Regenstein from elsewhere on campus, individual service and stacks spaces were also created in Regenstein for collections in Art, Music, and Classics.

Drawing all these disciplinary collections together and serving as a focus for bibliographic access to the entire building was the main card catalog of Regenstein Library, housed in long perpendicular rows of drawered cabinets stretching across the first floor immediately inside the entrance. For the first time visitor to Regenstein, few sights were more striking than this impressive bibliographic access tool, a physical and visual representation of the grand consolidation of knowledge now available within the walls of a single building.

Growing collections for research

As Regenstein Library opened in the fall of 1970, its collections were already growing rapidly in many ways, but particularly in international and areas studies. The federal Public Law 840 program of 1961 was providing significant ongoing levels of funding for the purchase of library materials. An $8.5 million grant to the University from the Ford Foundation, secured in 1966 just as the Regenstein family was making its $10 million gift for the building, brought five years of support for acquisitions in international and comparative studies and in non-Western area studies. Supplemented by grants under the U.S. National Defense Education Act, these funds assured the Library significantly enhanced collections, both in breadth and scale, in southern Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Near East and East Asia, and in Soviet and Slavic studies.

Through the 1970s and into the 1980s, Regenstein Library’s collections continued to grow through generous gifts and grants. Federal Title II-C grants provided funds for new acquisitions in southern Asian and Middle Eastern materials. Chicago collector Ludwig Rosenberger’s extensive collection on Jewish history and culture was given to the Library and housed in dedicated space in Special Collections. The Library was also able to secure $3.4 million in additional grants from the NEH, Mellon Foundation, and other sources for microfilming and other book preservation initiatives.

In 1997, the Library contracted with OCLC for the retrospective conversion of all bibliographic records in its manual card catalog, a process successfully completed in 1999. The conversion made possible a dramatic clearing of space in 2000, when the manual card catalog was removed from the first floor and replaced with new areas for reference support and student study.

Redesigning and reconfiguring to meet emerging needs

As these and other bibliographic and digitization initiatives moved forward, Regenstein Library also underwent the first major changes in its physical layout since its opening in 1970. Beginning in 1998, an extensive Regenstein Reconfiguration Project got underway, replacing fixed shelving on B-level with movable compact shelving, relocating collections to the new B-level stacks ranges, consolidating shelving locations of subject collections elsewhere in the building, and providing improved consultation spaces for faculty and student researchers. The addition of compact shelving on B-level, combined with additional fixed shelving ranges installed in the upper floor stack spaces, gave Regenstein Library a substantially increased capacity. From the original maximum projected storage of 2.9 million volumes in 1970, Regenstein’s total capacity had been expanded more than 50% to accommodate its current holdings of 4.5 million print volumes.

In 2003-2004, the University with the leadership of Martin Runkle and his successor Judi Nadler initiated an even more dramatic rethinking of the future of library spaces and services. Begun as a project for a Regenstein Library addition to the west, the Library expansion effort soon shifted to a broader program resulting in the construction of a completely separate library building. Designed by Chicago architect Helmut Jahn and connected to Regenstein Library by an enclosed bridge, the glass-domed Joe and Rika Mansueto Library opened in 2011. It provided capacity for 3.5 million volumes housed in automated storage and retrieval stacks extending five stories below ground. Under Mansueto’s dome, space was provided for an open reading room, enclosed individual studies, a circulation desk, and offices and work areas for the Library’s Preservation Department.

Access to the Mansueto Library required a broad new corridor, the Mansueto pathway, that cut a direct swath across the first floor of Regenstein Library. Extending from the main entrance of Regenstein, the pathway led to a dramatic cut through the west wall at a circular juncture known as the Knuckle. In the process of opening the new corridor, interior public and staff spaces in Regenstein needed to be reconfigured. The Special Collections Research Center was reoriented to face the new pathway, highlighted by an expanded exhibition gallery, all designed by the Chicago architectural firm Booth Hansen.

Other significant changes to the function and appearance of Regenstein Library followed. In 2011, reading room space in the northeast corner of the first floor was reshaped into a new and much expanded location for Ex Libris, the student-run coffee shop formerly located on A-level. In 2012-2013, Regenstein’s first floor was further reconfigured with a new home for meetings, conferences, and public events that were formerly housed on A-level. In space originally used for reserve circulation and study and later occupied by Inter Library Loan, architects Booth Hansen created a multipurpose room capable of seating 200 with a movable wall to divide the area into two interdependent function spaces. Located just off the main entrance lobby of Regenstein, this bright, expansive facility featured a full range of audio-visual technology and a completely equipped catering kitchen. Complementing these changes, the front entrance to Regenstein Library was reshaped with transformed circulation and reserves space, a new ID and privileges office, and visually appealing wooden entrance gates – all providing an important new point of entry and gathering for faculty, students, and members of the Library’s larger community.

In 2015, under the leadership of Brenda Johnson, the Library announced a further initiative to reshape Regenstein. Responding to student interest in more collaborative group working spaces, plans were implemented to reconfigure the general reading room on A-level into an interactive student learning center. The highly functional redesign began by introducing a welcome amount of light into the space through a new 72-foot floor to ceiling glass wall that provided views into the Jean F. Block Garden to the north. Within the interactive center, students were given a range of spaces for collaboration and study, with high work bars, lounge chairs, conference tables, and whiteboards. The reimagined A-level space was soon crowded with students, confirmation that the building known as The Reg retained its strong appeal for learning and social interchange.

While architectural reconfigurations over the years have shifted the use of spaces in the building, their success has shown the resilience and flexibility of the Netsch-Fussler design when adapted to new needs and technological advances. The vast multi-acre floor plates with few interrupting walls remain an emphatic physical endorsement of the integration and interdependence of intellectual fields, academic disciplines, and cross-disciplinary studies. And Regenstein’s continuing location at the heart of the campus serves as a reminder of the central role that the Library plays in exploring, expanding, and redefining the academic enterprise at the University of Chicago.