Where the intellectual meets the personal

Curator Lauren Stokes makes invisible histories visible in an exhibition on LGBTQ life at UChicago

University of Chicago History Ph.D. candidate Lauren Stokes curated the Special Collections Research Center’s spring exhibition, Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles: A History of LGBTQ Life at the University of Chicago. With the exhibition’s final days in the gallery approaching, Stokes answered Rachel Rosenberg’s questions about her research process, and described the connections and tensions between the LGBTQ experience on campus and the life of the mind.

Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles is a project of the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality. The project exhibition is on view in the Special Collections Exhibition Gallery through June 12, 2015. An associated web exhibit will remain online after the gallery exhibition closes.

How did you come to curate this exhibition, and what made you interested in doing so?

Following the success of the 2009 exhibition On Equal Terms: Educating Women at the University of Chicago at the Special Collections Research Center, the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality decided to sponsor a project on the history of LGBTQ life on campus. The University received a 5-star rating from the National LGBT-Friendly Campus Climate Index in 2012, but we knew very little about the work that it took to get to that point.

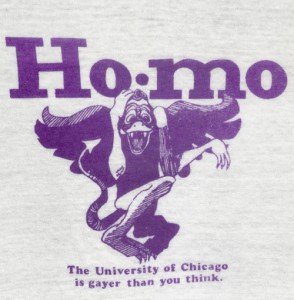

I was hired because I had previously researched the history of LGBTQ life at my undergraduate institution, which shares the same mascot as Chicago, so that I can now joke that I am truly the world’s expert on gay and lesbian phoenices.

What challenges did you face in working in the archives and conducting interviews? What were the most exciting discoveries you made?

Finding LGBTQ life in the archives is difficult because the terms that we use to describe what we are looking for are not the terms that would have been used in the past. More than with other projects I’ve worked on, I needed to do research before I could even do archival research, and I was indebted to previous work on Chicago’s LGBTQ history in order to provide a roadmap. Without the work of previous scholars, for example, I would never have been able to trace the network of “Boston marriages” among the first generation of female faculty and graduate students or have known where to find Gay Liberation in and around the University in the 1970s.

For oral histories, one of our biggest challenges was finding a diversity of narrators. In reaching out to narrators, we sought to span generations (resulting in a range from a 1958 JD to the 2012 AB), racial backgrounds, and sexual and gender identities and expressions. Many of the first volunteers were highly engaged with LGBTQ politics while at the University, but we were also committed to obtaining the stories of people who may not have been “out” or not have been LGBTQ-identified while on campus. For some of these people, we had to convince them that their experiences were also a necessary part of the history we wanted to preserve.

While curating the exhibit, I then confronted the additional challenge of translating these “invisible” histories, often characterized by silence, into object-based histories. Established institutional and political communities were more likely to leave material evidence of their existence. Now that the oral histories that speak to a different experience are in the archives, I hope that people will continue to use them in order to tell more “invisible” stories in creative ways.

Finally, Patti Gibbons at Special Collections worked to secure the loan of a square of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt that remembers some of the students and alumni who were lost to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. The quilt reminds visitors of an important chapter in local and national history, but also speaks to the silences that characterize the LGBTQ archive—many of the people we would have wanted to speak to about the early years of Gay Liberation died of AIDS-related causes.

AIDS also affected the material archive in surprising ways—there are many stories of birth families throwing out the personal items of sons and daughters who died of AIDS-related causes, while partners, lovers, and friends in the gay and lesbian community were legally unable to do anything about it.

Has your work on this exhibition enhanced your intellectual and professional development?

Thinking in terms of an exhibition is very different from thinking in terms of a dissertation. Not only was I telling a story with objects rather than texts, but I was also telling a story that had to arise from a community, and that had to do justice to the 96 people who were willing to share their stories with us.

I began with a great deal of anxiety about oral histories because I did not know if I would create “perfect” oral histories—what if I failed to connect with a narrator? What if I asked the wrong questions? It took the experience of several oral histories, and later the re-reading of those oral histories, before I became comfortable with the idea that “perfection” is not a useful concept for oral histories. An oral history is a conversation rather than a definitive statement of unassailable truth—but these are features of the method rather than problems to be solved.

Finally, I also had the opportunity to teach an undergraduate course about archival research as part of the project, “Sexuality and the Production of History” in Spring 2013. It was incredibly exciting to introduce students to archival research, and specifically how historians work with documents that at first glance may not seem to say much about sexuality. Those students also helped me to look at the documents in new ways, and their insights have filtered into the final product.

These same qualities—the value of collaboration and the ability to accept messiness and contingency as features of the sources that I work with—are also filtering into my other projects, which center on migration in German history.

How does this exhibit address the campaign for marriage equality? And what sort of impact do you want this exhibition to have on public conversations or future scholarly inquiries into LGBTQ history and rights?

The University of Chicago was one of the first universities nationally to offer benefits to same-sex domestic partners in December 1992, and the exhibit documents the faculty, staff, and student activism that made that possible. That moment also resonates with our contemporary moment because of the number of people who wanted to think “beyond marriage” and towards new ways of imagining intimacy and community.

The exhibit also uncovers a number of surprising activist strategies that might be worth reclaiming in the present, including coalition work between Gay Liberation and African-American groups in the 1960s and 1970s and queer students and hospital workers in the 1990s. I want everyone to know that LGBTQ people have always been part of the University, and that they have always worked to transform the University in creative and productive ways.

Finally, I think that the exhibit shifts our understanding of the University perhaps even more than it changes our understanding of LGBTQ life: because it was a theme that came up in almost all of the oral histories, I wanted to use the exhibit to explore the tension between the possibilities and the constraints created by the University’s focus on the “life of the mind.” For example, some narrators reported that their process of coming out influenced their path of study—one narrator remembered dropping a Political Science major in the 1960s because he didn’t think he could be a gay politician, while some of our narrators from the 1980s chose to go to law school so that they could make a difference in the AIDS epidemic. At an even more basic level, some of the narrators from the 1960s chose Chicago in part because Illinois was the only state that had decriminalized sodomy. The experiences of LGBTQ individuals offer special insight into the ways that none of our intellectual lives can be separated from our personal lives.