From Books to Journals: Words in Action

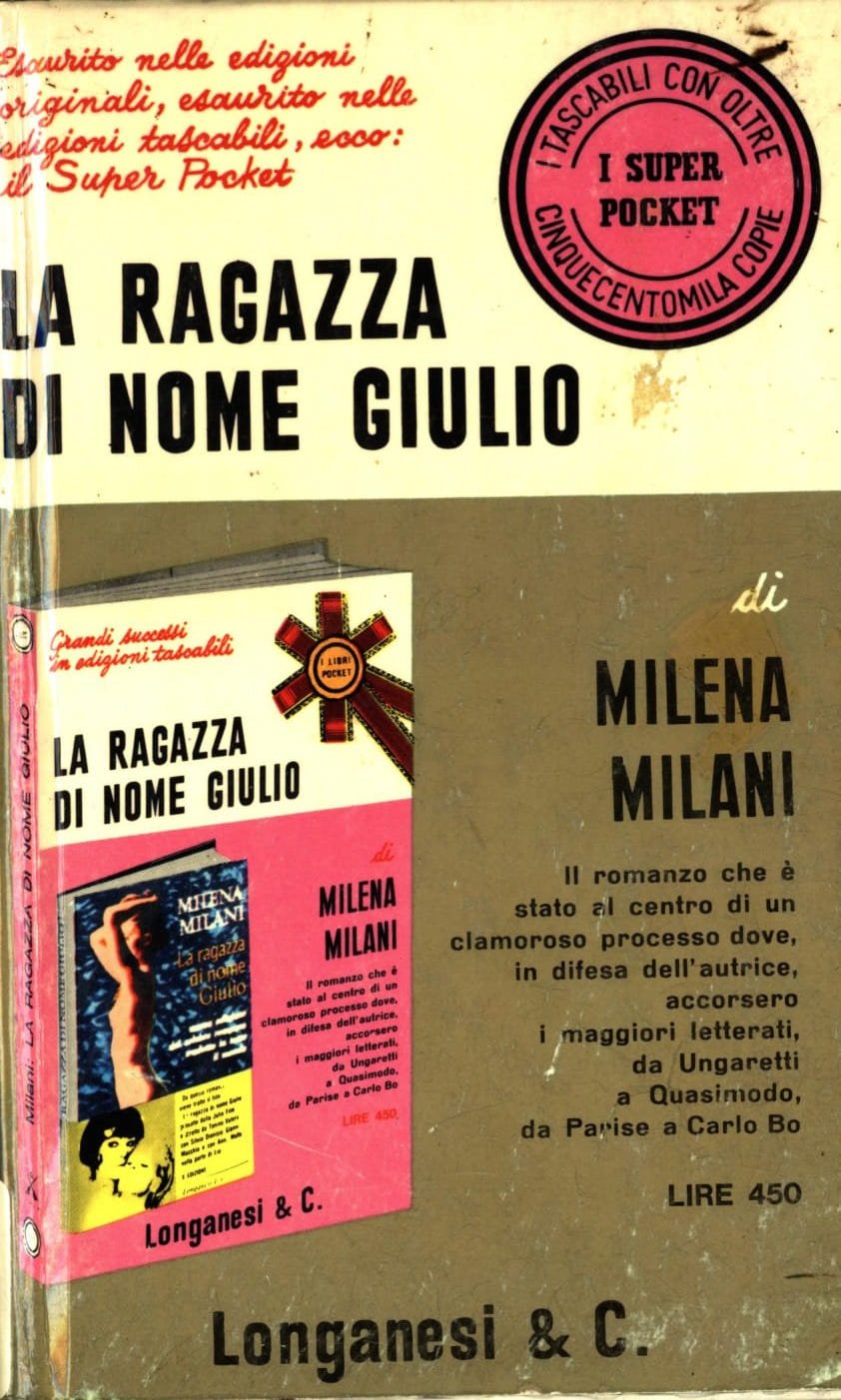

Milena Milani

This book is considered the earliest pioneering feminist assessment of female identity and sexual difference in fascist Italy. Upon its initial release in 1964, the novel was at the center of a clamorous trial for having “gravely offended a common sense of decency.” Milena Milani (1917-2013) was abandoned by her publisher, labeled a pornographer, and condemned to six months of prison. The intellectual world, led by Giuseppe Ungaretti, opposed to both the censorship of the novel and Milani's charge. She ended up winning the appeal case in 1967 and the novel was re-released the following year.

The story is narrated in the first-person and recounts the coming of age in fascist Italy of a girl, Giulio (named after her foreign father, Jules; the author then changes the name to its Italian equivalent while maintaining the masculine -o). Giulio claims her corporality both as a form of liberation, and as a means of uttering a desperate cry for female emancipation. The author openly discussed themes such as female homosexuality, menstruation, and dissatisfaction of relationships with men, which were considered extremely scandalous and inappropriate. Nonetheless, her political position and progressive ideas anticipated those expressed with the Women's Movement in the 1970s and powerfully undermined the authority of patriarchal preconceptions of history, sexuality, and narrative.

Hans Ruesch

Hans Ruesch (1913-2007), born in Naples from Swiss parents, is internationally known as an outspoken advocate against vivisection and other forms of animal testing. In 1974, he founded the Center for Scientific Information on Vivisection (CIVIS) and devoted the rest of his life to the abolition of vivisection. In the 1970s, Ruesch started writing exposés of the animal testing and research industry and wrote the Naked Empress, or The Great Medical Fraud, which he then also translated into English, where he denounces the brutal practices of animal exploitation in laboratories.

The Italian vivisection movement, which originated in England at the end of the 19th century, became particularly active in these years and this book was central in bringing the topic at a national level and causing important legislative reforms.

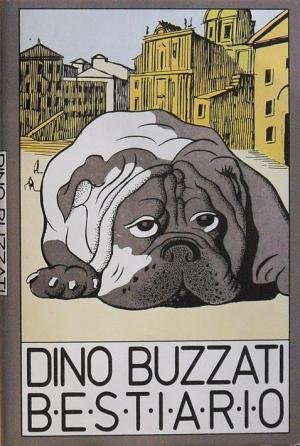

Dino Buzzati

Dino Buzzati (1906-1972) was an Italian novelist, short story writer, painter, as well as a journalist for Corriere della Sera. He is best known for his novels, such as The Tartar Steppe, and lesser known for his vital work and support of animal rights.

The issue of animal exploitation and suffering caused by humans was extremely important to him and became a crucial part of his political engagement. He wrote several articles defending oppressed animals and denouncing cases of animal cruelty: for instance, he wrote a petition to the mayor of Milan advocating for the life of a seal suffering in a small enclosure in the city zoo; he wrote a letter to the Secretary-General after learning about the death of an eagle shot at the Quirinale, one of the residences of the President of the Italian Republic; he denounced the Russian scientists who sent Laika, the Soviet dog, into outer space in 1957, causing her unnecessary suffering and death in the name of science and human progress. Oleg Georgivitch Gazenko, Laika's trainer for the space flight, admitted in 1998 that “Work with animals is a source of suffering for all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I'm sorry about it. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog.”

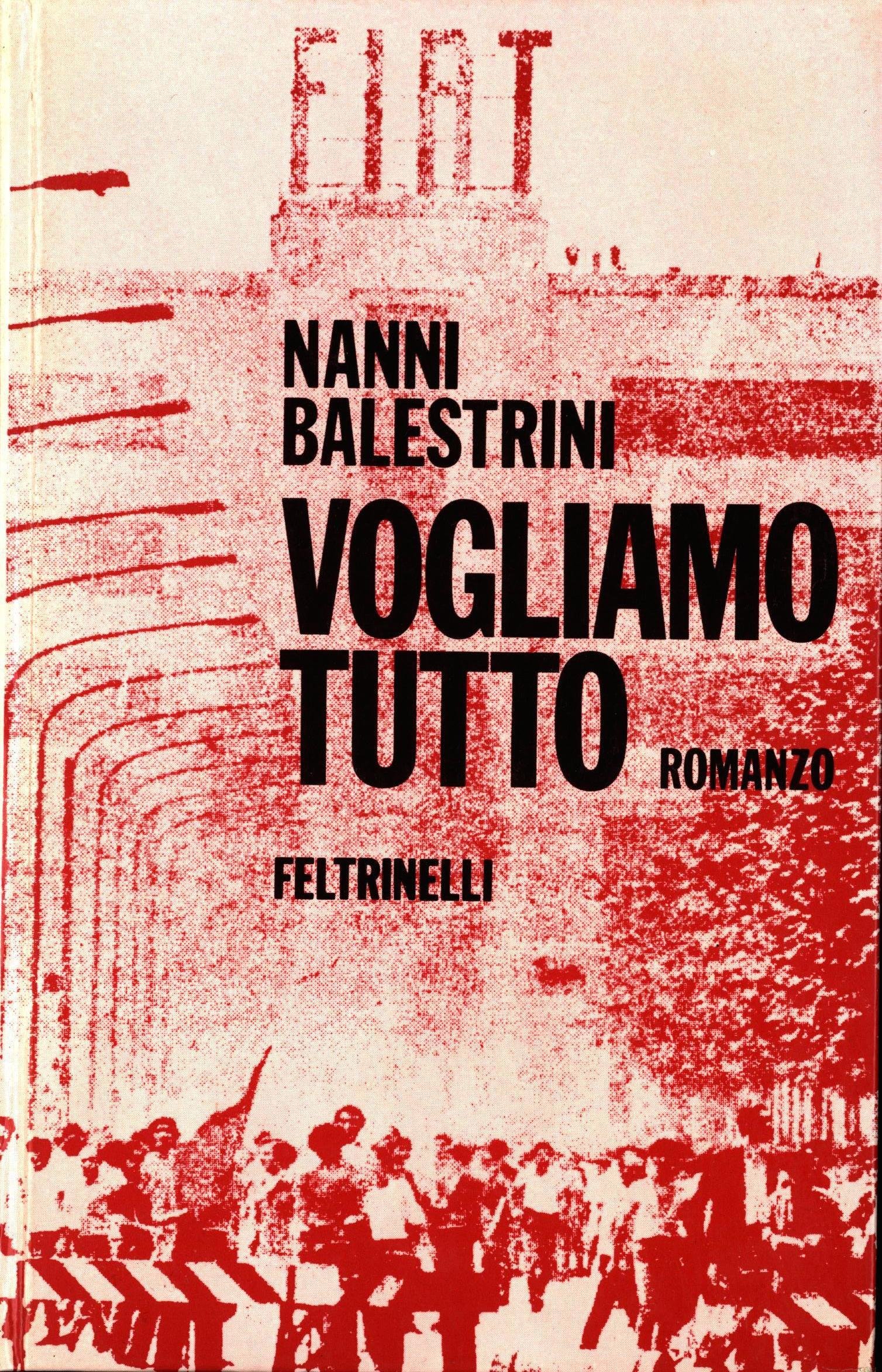

Nanni Balestrini

This revolutionary and incendiary novel, only recently translated into English (We Want Everything, 2016), unveils a fictionalized version of Italy’s historic “Hot Autumn” of 1969, when workers around the nation organized massive mobilizations demanding better working conditions and wages. The inspiration for the novel derives from the experiences of a real person, Alfonso Natella, who arrived at Fiat’s Mirafiori factory in Turin from the impoverished south. His name deliberately never appears in the novel. The protagonist must in fact be considered a collective character, since in those years thousands of people could identify with him and see their own thoughts reflected in his.

In this book, Nanni Balestrini (1935-) exceptionally describes the alienating life of workers: “Every Fiat worker has a gate number, a corridor number, a locker room number, a locker number, a workshop number, a line number, a number for the tasks they have to do, a number for the parts of the car they have to make. In other words, it’s all numbers, your day at Fiat is divided up, organized by this series of numbers that you see and by others that you don’t see. By a series of numbered and obligatory things. Being inside there means that as you enter the gate you have to go like this with a numbered ID card, then you have to take that numbered staircase turning to the right, then that numbered corridor. And so on.”

Carla Lonzi

Carla Lonzi (1931-1982), was an art critic, a politically creative woman seeking freedom, and above all an emblematic and influential figure in promoting the most radical wave of theorization of Italian feminism. In the diary she kept between 1972 and 1977, Taci, Anzi Parla (Shut Up, Rather Speak), she writes: “Through feminism I freed myself from the inferiority-culpability of being clitoridian … and I accused men of everything. Then I started to doubt myself and to defend myself through every possible thought and inquiry into the past. Then I doubted myself completely in rivers of tears … After that I was no longer innocent or guilty.” So for Lonzi, as developed in her radical text La Donna Clitoridea e la Donna Vaginale (The Clitoral Woman and the Vaginal Woman, 1974), being a woman has not only sexual connotations, but also existential and political ones.

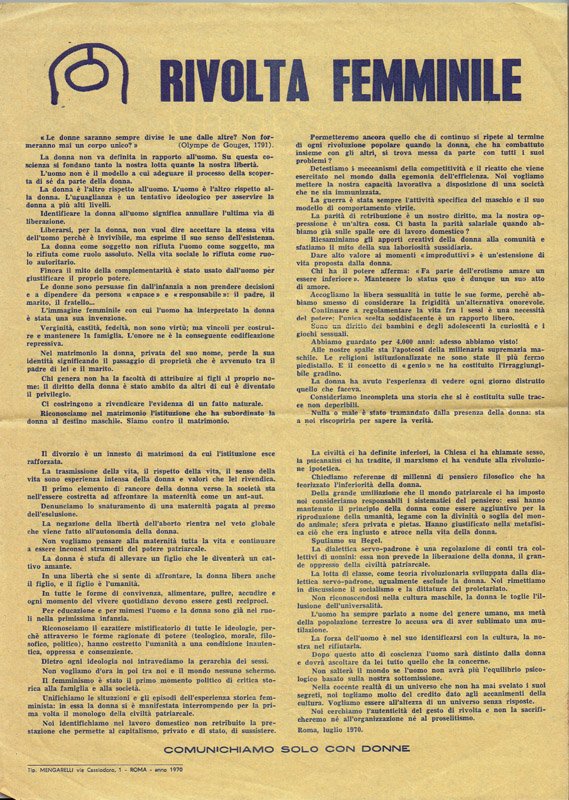

Lonzi founded the group Rivolta Femminile and posted up a manifesto on the walls of Rome in 1970 (Manifesto of Women's Revolt) signed also by Carla Accardi and Elvira Banotti, which was then published in both Milan and Rome along with the essay Sputiamo su Hegel (We Spit on Hegel). The feminist movement in Italy, slower to advance compared to other countries, challenged the rigid Catholic morals of society and a legal system that gave women little defense against male oppression, rape, or even murder. The great victories in the referendums of the 1970s and 1980s on divorce and abortion would have been impossible without the agitation of the feminist movement and women like Carla Lonzi.

Leonardo Sciascia

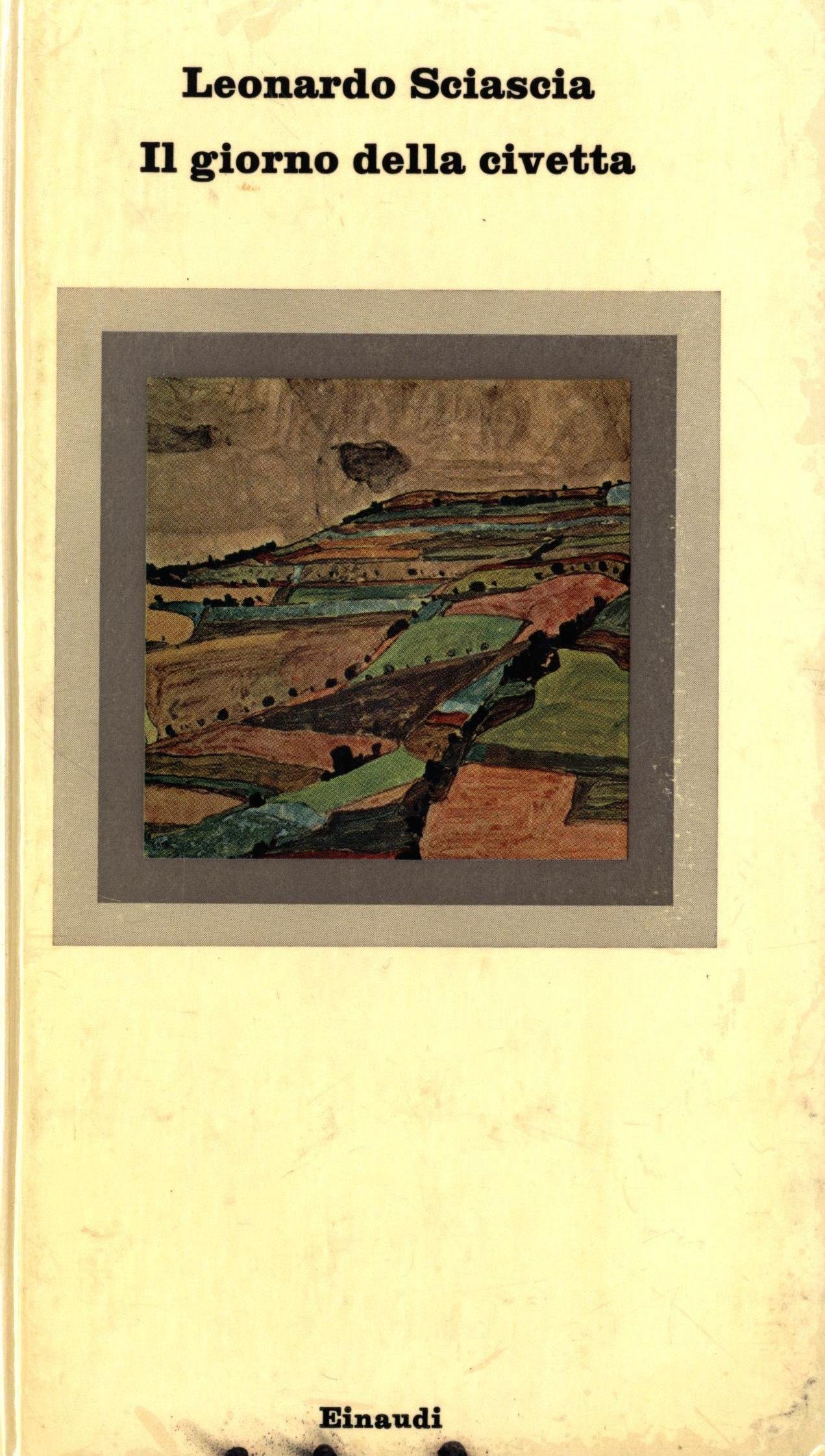

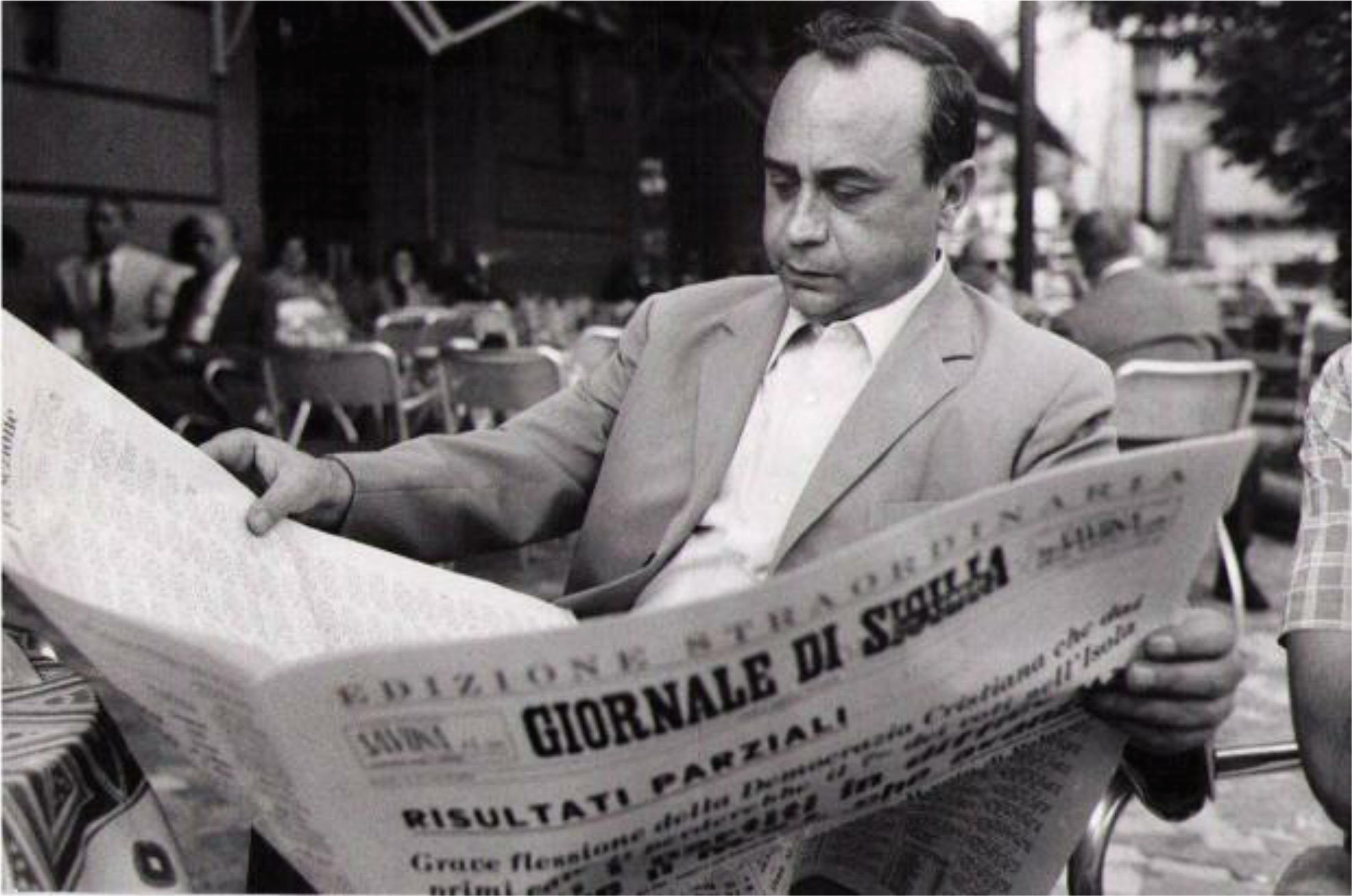

Leonardo Sciascia (1921-1989) is remembered as the Sicilian novelist who wrote about the Mafia and for his strong political and social commitment. He actively participated to the political life of the country: after leaving the Communist Party, Sciascia became in the last years of his life a member of the Radical Party, and was then elected as a Radical to both the Italian and the European Parliament. He also became a member of the committee of the House for the investigation into Aldo Moro's kidnapping and assassination, which led to presenting a forensic analysis of the case in the famous book L'Affaire Moro (The Moro Affair, 1978).

His distinctive detective stories present unsolved crimes, defeated detectives, silences and omissions. Sicily is the setting of many of his novels, as in the case of Il Giorno della Civetta (The Day of the Owl), which is inspired by the assassination of Accursio Miraglia, a communist trade unionist, at Sciacca in January 1947. The readers were introduced to the mechanisms of the Mafia at a time in which the existence of the Mafia itself was debated and denied. Its publishing led to a widespread debate and to renewed awareness of the phenomenon. Damiano Damiani directed a movie adaptation in 1968.

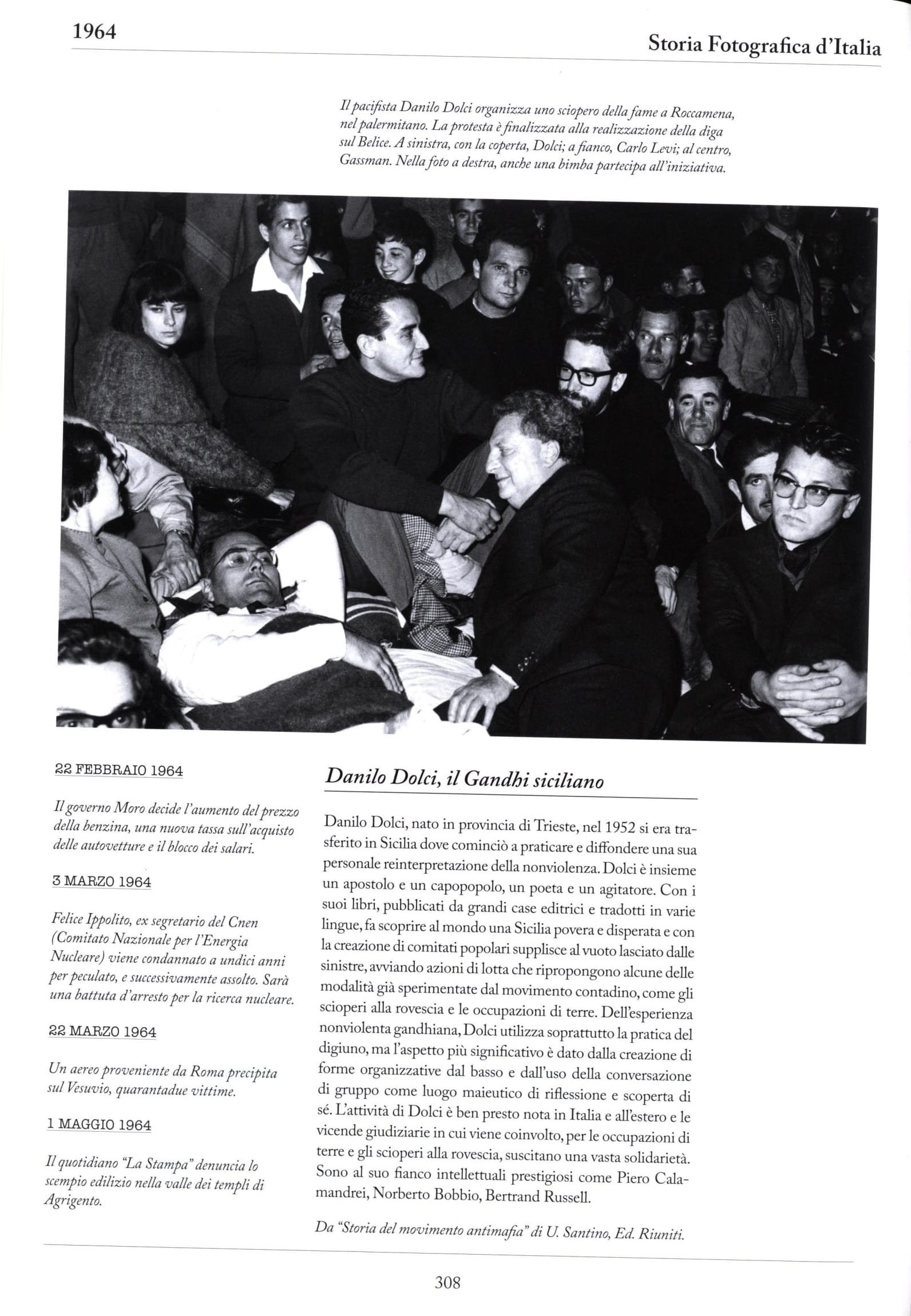

Danilo Dolci

Danilo Dolci (1924-1997) was an Italian poet, social activist and educator. He is known for his opposition to poverty, social exclusion, and the Mafia in Sicily, and is considered one of the main figures of the Italian non-violent movement. During his life he was always close to the disadvantaged and oppressed groups in Sicily. He was also convinced that the key to progress was through education, and therefore set up his own study centre in Partinico, a village near Palermo.

This book (Who Knows if Fish Can Cry) published in 1973, best illustrates his ideas and ideals of education. His pedagogical methods are characterized by an emphasis on social awareness and cultural interaction, by teaching the importance of being involved in the peaceful civic fight, and he considers the educational commitment a necessary element to create a more open and responsible civic society.

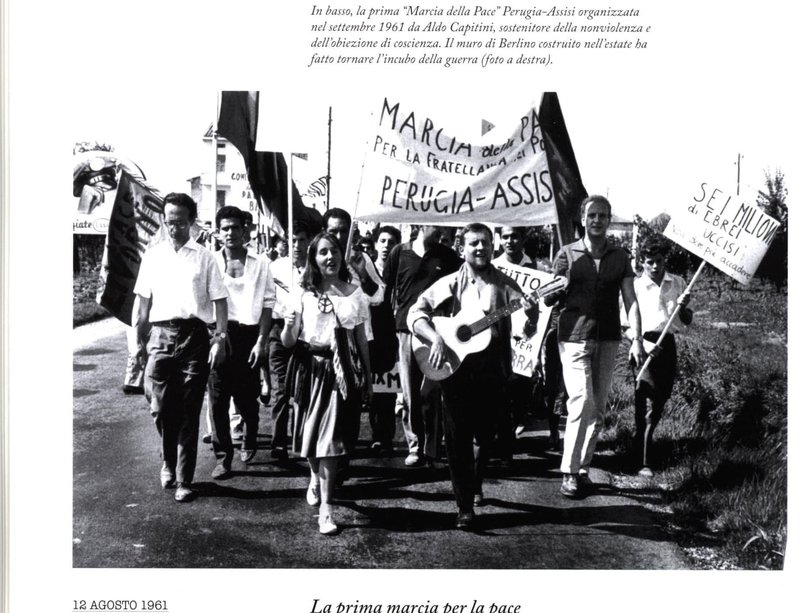

Aldo Capitini

Aldo Capitini (1899-1968) was an Italian philosopher, poet, political activist, anti-Fascist and educator. He was a courageous advocate of an active and positive conception of nonviolence and believed in the primacy of direct action, which is why he was imprisoned twice in Fascist era, and also why he organized the first march for peace from Perugia to Assisi, in 1961. Capitini was also the founder of the Italian Vegetarian Society. He in fact advocated for peace for all beings, not only humans, since he was aware of the interconnection between oppressions and believed that as long as humans kill other animals, peace on earth would never occur.

In this book (The Techniques of Nonviolence), published in 1967, Capitini discusses individual and collective techniques for nonviolence, emphasizing the need for training so that when the time comes to use them, we are not unprepared. He also includes examples of nonviolent strategies and cases that have been deemed successful, because he strongly believed that the effectiveness of the nonviolent method must not go unnoticed.