Music and Movies: Words in Motion

Luigi Nono

Luigi Nono (1924-1990) was one of the pioneers of the post-war avant-garde alongside Boulez and Stockhausen. His passion and commitment to radical political issues caused him to rarely be accepted by the musical establishment. During the 1960s, Nono's music, recognizable for its electronic experimentation, became increasingly explicit and polemical, and it often caused scandal. The premiere of Intolleranza 60, for instance, at La Fenice in Venice, provoked a strong reaction in the public. In his review of the event, Eugenio Montale wrote: “The two acts came off with great difficulty, among boos, shouts, altercations, fascist flyers raining down from the galleries.” In his works, Nono took on several causes, from his condemnation of Nazi war criminals in Ricorda cosi ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz, 1965 (Remember What They Did to You in Auschwitz) to his support for the student uprising of May 1968 in Non Consumiamo Marx (Let's Not Consume Marx).

La Fabbrica Illuminata (The Illuminated Factory, 1964) is dedicated to the workers of the metallurgy plant Italsider in Genoa and sheds light on the many injustices that faced the workers, including low wages, dangerous workplace environments, and mental health problems. Most of the material for this piece was recorded at the factory, such as production noises and recorded speeches, to better convey the alienation and suffering of the Italian workers.

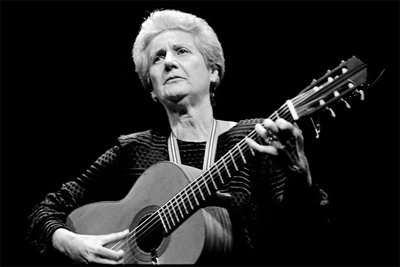

Giovanna Marini

Giovanna Marini, born in Rome in a family of musicians, is one of the most important voices in the scene of Italian popular music. During her long musical career she became famous for her lyrics embracing the themes of several political and social issues. She was a member of the group Nuovo Canzoniere Italiano, together with Roberto Leydi, Ivan Della Mea, Sandra Mantovani, and others, and participated in the historical Spoleto Festival “Bella Ciao” in 1964.

The song I Treni per Reggio Calabria (Trains to Reggio Calabria, 1973) was written to commemorate the events that occurred on a specific day: October 22nd, 1972. A major workers' protest was scheduled on that day in the southern city of Reggio Calabria and over forty thousand people traveled south by train to support the workers' fight for justice. Right wing groups attempted to impede their arrival and disrupt the rally, and nine terrorist attacks took place during the night between the 21 and 22 October. Although bombs were placed on a number of those trains and on railway tracks, nothing stopped the historical march from happening.

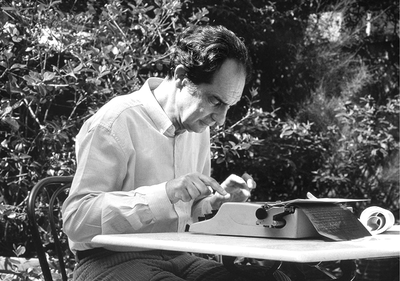

Italo Calvino

On May 1st, 1958, the famous writer Italo Calvino (1923-1985) debuted as a songwriter. The song Dove Vola l'Avvoltoio (Where Does the Vulture Fly), for which he wrote the lyrics and Sergio Liberovici the music, was played over loudspeakers at the CGIL (General Confederation of Labour) trade union parade in Turin. The refrain sings: “Fly away, vulture, / fly away from my land, / because it is the land of love.” This pacifist song, sending a clear message against war and nuclear weapons, has become the emblem of the group Cantacronache.

Cantacronache was an open group of artists and musicians active from 1958 to 1962 whose slogan was “evadere l'evasione” (escape escapism). The main feature of their songs was the depth of the ideas expressed, especially their focus on social issues. Their songs represented a significant break with the music establishment that supported the consumerist and melodic canzonette promoted for instance at the Sanremo festival. The work launched by this anti-conformist group would set the ground for future memorable cantautori, such as Fabrizio De André and Francesco Guccini.

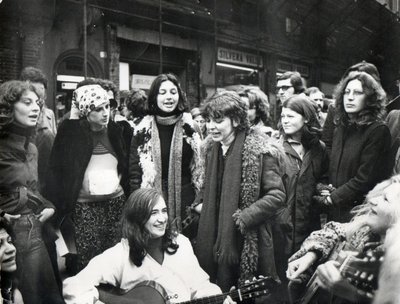

Canzoniere Femminista

The feminist protest in music has a very peculiar history in the '70 in northern Italy, especially in Veneto. A group of women, members of the Comitato per il salario al lavoro domestico di Padova e Venezia (Padua and Venice Wages for Housework Committee), chose a unique and creative method to convey their revolutionary messages: protest songs. Some of the central figures of this movement are Laura Morato, Maria Pia Turri, Rosalba Sciaulino, Luisa e Lucia Basso. They recorded two albums: Canti di donne in lotta and Amore e Potere. In their songs they make explicit and strong requests, expressed their problems, suffering, and achievements. They fight against clandestine abortion, domestic violence, against stereotypes, social and economic inequality, oppression and exploitation; they attack the male vision of history, the Christian principles discriminating women, the capitalist ideology, the traditional family structure; they feel the urgency to tell a story that is not male dominated, they don't want to remain behind the scenes, they want their voices to be heard.

The last lines of the song Noi Donne (We Women, 1974) encapsulate their spirit: we want our freedom / the courage to fight against normality / the strength to choose the life we want / the power to be, to be what we want to be.

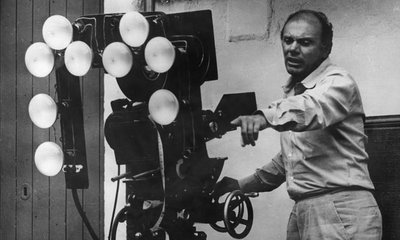

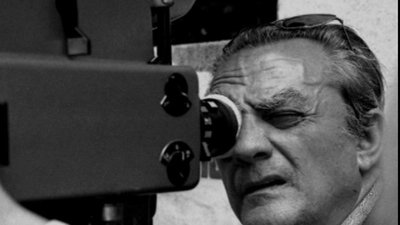

Francesco Rosi

Le Mani Sulla Città (Hands Over the City, 1963), is a drama film directed by Francesco Rosi (1922-2015) set in post-war Italy. With great civic courage, Rosi offers a compelling look at the political corruption, capitalist greed, and house speculation in Naples. The movie opens with a scene of a building collapsing that leaves two people to die. This scandalous event brings to surface the shady political schemes, interests, and backroom deals of a building speculator who uses his powerful position in the city hall to manipulate the investigation to his advantage.

The director filmed using many real-life Neapolitan politicians in the cast. The final caption reads: “All the personalities and events in this film are fictional. But the economic and social conditions which gave rise to the story are not fiction.” The movie won the Golden Lion award of the Venice Film Festival in 1963.

Elio Petri

La Classe Operaia Va in Paradiso (The Working Class Goes to Heaven, U.S. release title Lulu the Tool, 1971) is a movie directed by Elio Petri (1929-1982) that follows and renews a long tradition of cinema d’impegno (politically and civically engaged cinema), which saw its early beginnings in neo-realism and reached its peak in the 1960s and 1970s. This harsh and thought-provoking critique of industrial capitalism, features the exceptional actor Gian Maria Volonté playing Lulu, a factory worker in Turin, victim of the process of mechanical production and mass consumption. In his famous speech during an agitation at the factory, Lulu yells to the crowd: “We are like a machine... I'm a machine, a pulley, a screw, a piston rod, a transmission belt, I'm a pump, a broken pump, and there's no way to repair that pump now. I suggest to stop working right now. All.”

Suddenly, a multitude of movies were being produced in which proletarians and workers were featured characters, such as Lina Wertmuller's Mimì Metallurgico Ferito nell'Onore (The seduction of Mimi, 1972), Ettore Scola's Trevico-Torino (From Trevico to Turin, 1973), Luigi Comencini's Delitto d'Amore (Somewhere Beyond Love, 1974), and Mario Monicelli's Romanzo Popolare (Come Home and Meet My Wife, 1974).

Luchino Visconti

Rocco e i suoi Fratelli (Rocco and His Brothers, 1960), directed by Luchino Visconti (1906-1976), is a social melodrama that has become a classic of Italian cinema. The 1950s represented a period of mass internal migration in Italy and the movie enables a rigorous analysis of this socio-historical change. Set in Milan, it narrates the anthropological mutation that took place during the prosperous years of the industrialization of Northern Italy and the traumatic changes that the southern peasants had to endure as they struggled to become part of the industrialized world.

The portrayal of South-North immigration renders in a very realistic way the geographical and psychological demarcation that characterizes the country. Already from the opening shots showing the family arriving at Milan’s central station, their struggle to adapt to a new reality is evident. The intimate family drama allows the viewers to get a sense of and feel the symptoms, trauma and overall affect of social transformation. The movie won 22 international awards.

Lina Wertmüller

The lack of women in strategic positions in cinema has a long history. Lina Wertmüller (pseudonym of Arcangela Felice Assunta, 1928-) is one of the few women filmmakers of these years that has received international recognition in the male-dominated film industry. In 1976 she stated: “My films are deliberately provocative, intended to agitate problems and bring them out in the open. This is my aim- to provoke and discuss.” Her politics are not abstract or purely ideological. She is in fact interested in topics such as youth and drug problems, proletarian conflicts, the feminist movement, the power of mass media. From her films one can construct a sociopolitical perspective of these years and can also understand the moral concerns about the individual trapped by the forces of power structures.

In Mimì il Metallurgico Ferito nell'Onore (Seduction of Mimi, 1971), she traces the evolution of a young man in a political swing of the pendulum from Left to Right in Sicily. Wertmüller manages in a single movie to denounce the Mafia, politics, justice, social equality. Ennio Morricone's “metallic” music accentuates even more the robotic gestures of the factory workers.

Marco Bellocchio

Italy's tense political climate had exploded in the student uprisings of 1968, which had become nationwide, as students contested not just the education system but the whole structure of society. Discutiamo, Discutiamo (Let's Discuss, 1969), marks the beginning of Marco Bellocchio's militant film-making and would be swiftly followed by his two propaganda documentaries for the UCI later in the same year (Paola and Viva il Primo Maggio Rosso, Long Live Red May Day).

This short movie tackles politics without wavering. In 24 minutes, Marco Bellocchio (1939-) narrates an iconic exemplum of student contestation, with a cast consisting of students from La Sapienza University of Rome. Bellocchio's political position towards students' protests is controversial and he explicitly declares his point of view in an interview: “As students today in Italy have understood-and not only students but every sincere revolutionary- the thing to do today is not to demonstrate and get beaten by the police but to get organized in a party with, of course, the proper kind of principles. The director too, as a revolutionary artist- if we want to define him this way and if he wants to be one, for this involves a certain amount of sacrifice for him-has to work for that political organization. That's all.” The short movie was part of a collective project originally called Vangelo '70, comprised of four other short movies by Bertolucci, Godard, Lizzani, Pasolini, now known as Amore e rabbia (or La Contestation).