Representing the Unseen

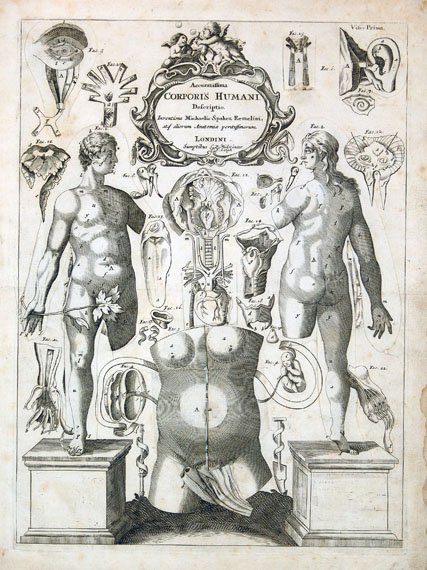

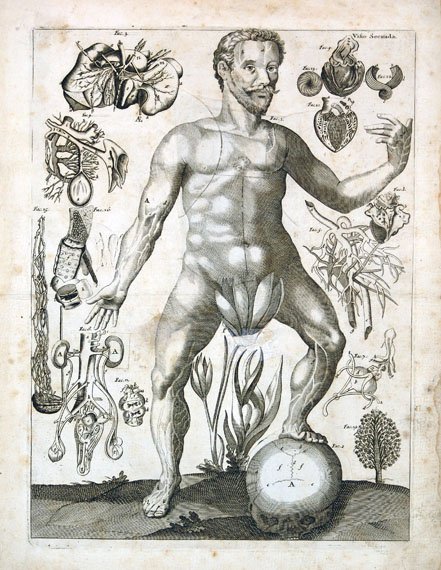

To discover is to uncover: the two books in this section help readers see beneath the surface. The extraordinary interactive flap-anatomies in Johan Remmelin's anatomical atlas (Item 1) allow the reader to replicate the process of dissection by folding back consecutive bodily surfaces: from skin to muscle and organs, to arteries, veins and nerves, to bone. The book invites its user to "practice" anatomical discovery by moving between the facing pages: between image and index, looking and reading, dividing and ordering. The negotiation between text and image involves the reader in a second movement down into the layers of the book and body. This process of uncovering is at once empirical in orientation and symbolic. Notice (Item 2), for example, how the unfolding of the skull transforms a traditionally iconicmemento mori into physiology, and how the leaves covering the man's genitalia invite the reader to find a new kind of scientific knowledge within a symbolics of modesty and immodesty, innocence and shame.

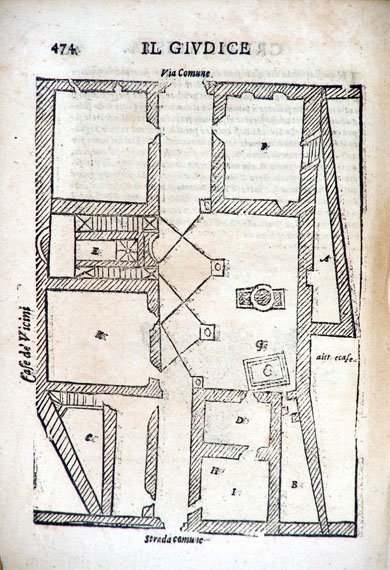

Another early science of discovery is exemplified by Antonio Cospi's Il Giudice Criminalista (Item 3), a manual on criminal investigation with sections, for example, on poison, physiognomy, demonology and forensics. In the illustration shown, included in a section on how to investigate a homicide, Cospi is modeling how a notary might help a judge by drawing a plan of a house so as to expose within it possible secret rooms or hiding places. The accompanying text leads the viewer through the home, detailing entries to the concealed spaces A, B, C, D and E through, for example, a small staircase behind a fireplace in room F, a sinkhole (G) in the central courtyard, a wardrobe (H) in room I, and a spiral staircase descending from the roof at E. In the wrong hands, of course, Cospi's architectural scheme could be used for constructing rather than detecting secret spaces. Useful in practical terms, both Cospi's and Remmelin's books give their readers methods for seeing surfaces less as obstacles to knowledge than as starting points for thought.