Commonplace Thinking

A commonplace book is at once a book form and a method of reading. Commonplacing was a system of using books in which readers digested the books they read by extracting, ordering and recording particular phrases or passages in notebooks of their own. This process encouraged readers to atomize books by isolating units that might later be useful in one or another discursive context. While the commonplace book allowed readers to personalize their reading by making it useful, this process of textual engagement was also highly prescribed, "common" in the sense that it filtered one's reading through social norms that determined what was textually significant and what not.

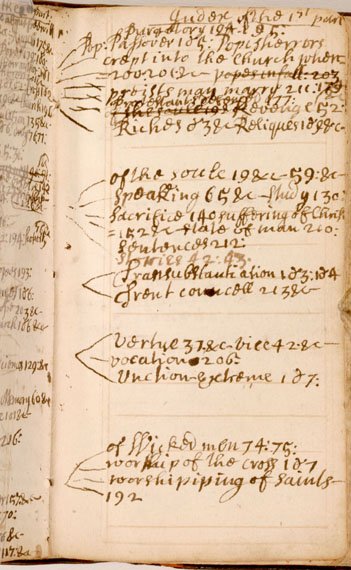

The early pages of Thomas Ducke's c. 1619 commonplace book (Item 1) digested material under general headings corresponding to the order of the Christian universe (God, Christ, Law, Heaven, etc.). His interests, however, go beyond the theological to include, for example, a long list of amusing stories, presumably compiled for his pleasure or to help him remember them for later use at a dinner table. By their nature, manuscript commonplace books such as Ducke's would seem to be most useful to their compiler. This was not always the case. An interesting feature of the book is that it was used by a second reader around 1686, one Edward Jones, who supplemented it by adding stories and jokes, mainly of a sexual nature. Most remarkably, he added an index to the pages compiled by Ducke 60 years earlier. Jones's appropriation of Ducke's book can be seen as a logical endpoint for a process in which all reading was appropriation.

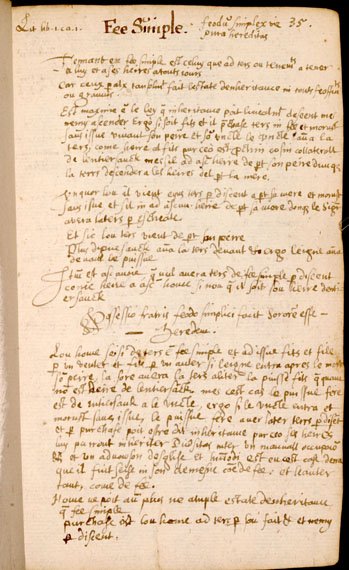

The small early seventeenth-century legal commonplace book (Item 2) was probably compiled by a law student at the Inns of Court in London. Although it had a specific professional function, the book can also be seen as a personal document in the way Ducke's more wide-ranging book is, since it was through such books that lawyers made a disciplinary structure their own. Drawing both on written texts and on oral sources, including legal decisions in the courts and exercises central to legal training, lawyers used commonplacing to synthesize information, thereby helping to constitute the law as a field of textual practice.

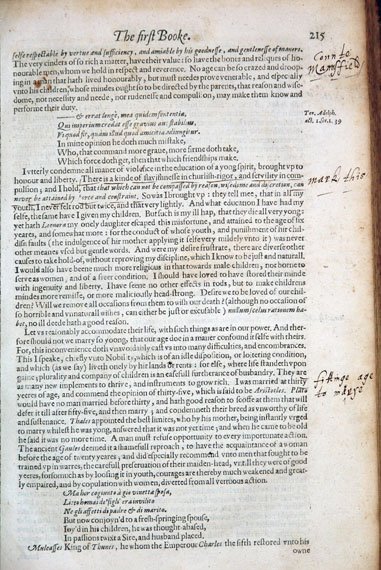

Michel de Montaigne's Essais (Item 3) famously began as his commonplace book. The topical structure of the book and the individual essays ("De l'amitié," "Des cannibales" "Du Dormir") mirrors the commonplace organization of material. In a nice reversal of the process whereby Montaigne made his book, an early English reader of John Florio's translation of Montaigne (Item 4) seems to have digested the essays according to topics of his own. His annotations variously underscore Montaigne's text, as with his emphatic "mark this" and his approving "a fittinge age to mayrye." Most interestingly, he makes Montaigne's generic description of a military hero historical and local, by identifying the type with the German "Count Mannsfield," a leader whose visits to London in 1624 consolidated his English reputation for heroism. Sometimes the reader follows Montaigne's categories, sometimes not. On one page, next to a famous anecdote about a woman who turned into a man by jumping over a fence, the English reader has written "for wenches lepeing [leaping]." Has he imagined this improbable heading as a category of use or thought?