Marking Books

One way to mark a book is to write one's name in it. This is a mark of identification, ownership, property, but not necessarily use. The three texts in this section carry signs of ownership and also of private and public use. The cover of the small Bible (Item 1) was embroidered, and its front edge elaborately decorated, by the Nuns of Little Gidding in the early seventeenth century. Given that books in this period were often bought unbound, a binding could indicate the owner's economic status and his or her (as opposed to the author's) sense of the book. This binding is unusually expressive of the owner's relation to the book as a precious object for devotional use.

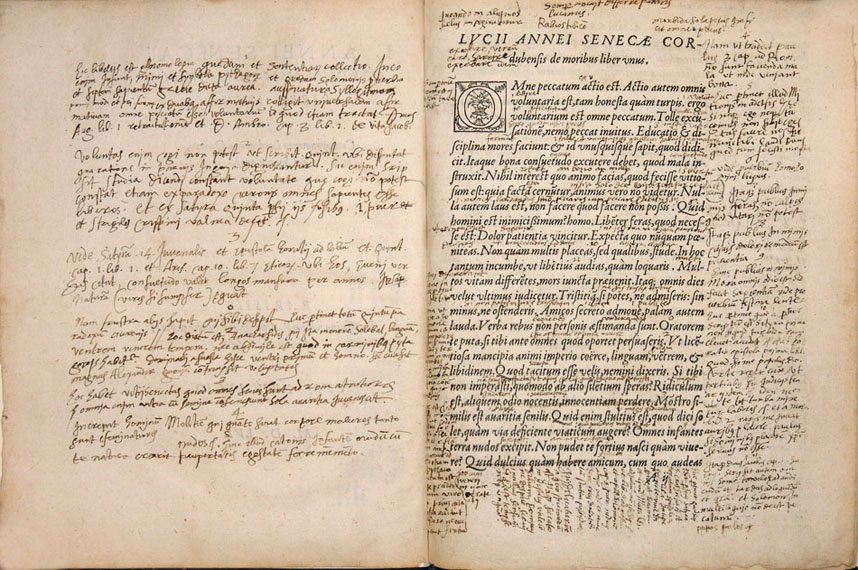

As is true today, early readers wrote in their books by underlining passages of interest, or by adding commentary, queries, objections. The short text edited by Léger Duchenne (Item 2), made up of proverbs and maxims spuriously attributed to the Roman philosopher Seneca, was printed for use at the University of Paris. While marginalia are often a striking index of personal engagement, the manuscript annotations (c. 1560) that fill this book and its margins are probably a student's notes on his professor's lecture, and thus point to a complex negotiation among readers experiencing and using the text collectively.

The writing on the pages of Thomas Lodge's play (Item 3) point even more dramatically toward a collective form of use. These marks tell us that we are looking at a rare early prompt-book, a copy of a play used by a theater company to adapt it for use in dramatic performance. On the page shown, a passage has been cut, stage effects indicated ("musick," "thunder," "Lightening," "Arbor rises"), and a stage direction added to compensate for the cut ("Ent[er] Ras[ni] Lordes & magi not paph[lagonian king])." As with the other two books in this section, use transformed this book by directing it toward a particular end, and by positioning it within a social and institutional practice.