The Fight Continues

The Illinois Society for Medical Research Records

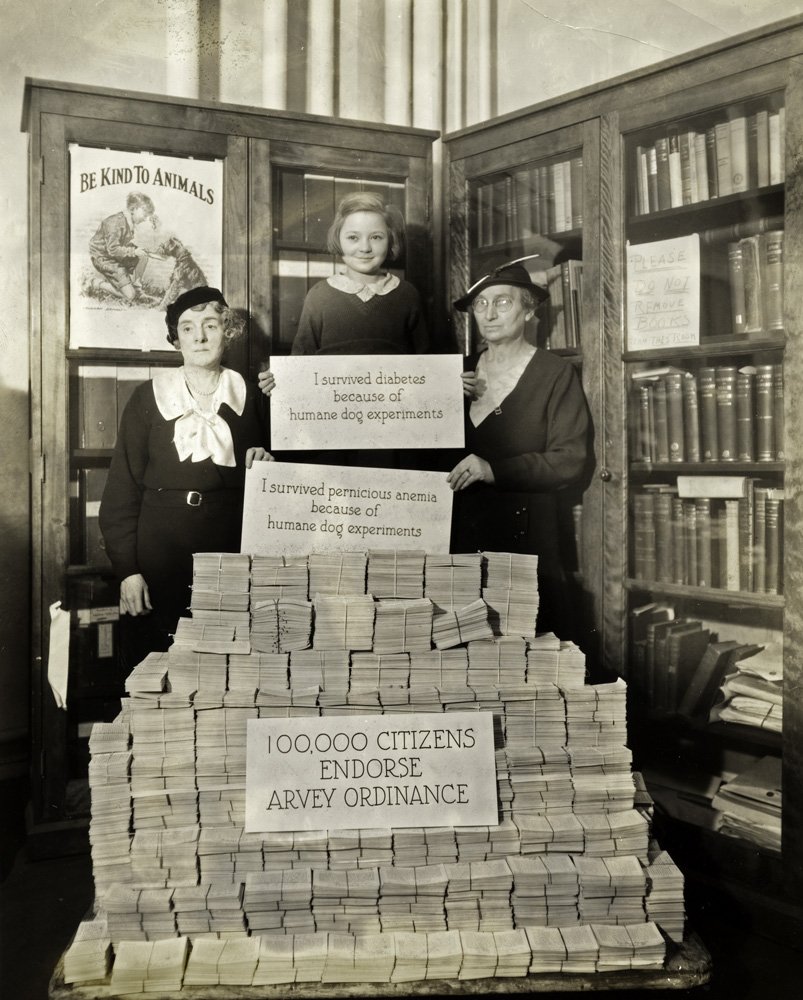

In the fall of 1930, the wives of Northwestern physiologists launched a campaign to demonstrate public support for the Arvey Ordinance. Over 150,000 people participated, and their cards form tall stacks in this photograph taken in Ivy’s office. Enlisting children who had survived diseases thanks to animal research, such as the girl posing here, was a popular tactic.

Scientists hoped the passage of the Arvey Ordinance would put an end to their legal troubles, but Drs. Carlson, Ivy, and their associates found themselves fighting a near-constant battle for the next two decades. Ivy once estimated that, in the four years following the passage of the Arvey Ordinance, he spent nine months combatting legal challenges from Irene Castle, who launched multiple campaigns to repeal the measure and filed a series of injunctions against the city.

By enshrining the medical schools’ access to dogs, free of charge, the Arvey Ordinance enabled antivivisectionists to critique the economic preference given to Chicago’s universities instead of more abstract ethical aspects of animal experimentation. During the Depression era, Castle shrewdly framed her position in populist terms. “I can see no more reason why the city should give the universities their material for physiology classes than that they should make them a present of all confiscated cars, liquors, drugs, food supplies…as they might need for all their various studies,” she told one reporter. The “poor man,” Castle often argued, could not afford to retrieve his dog from the pound before it was claimed by doctors. The law, she said, favored both wealthy pet owners and institutions.

As the press devoted more space to the controversy, prominent doctors received a steady stream of hate mail and personal threats.