The Children's War

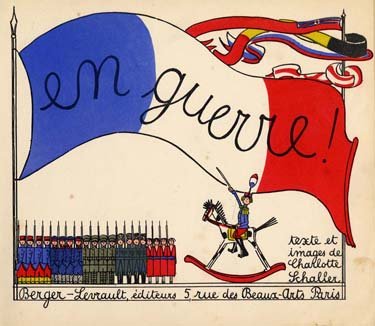

Perhaps because the young would inherit the legacy of victory or defeat, children's literature devoted to the theme of the war was very wide-spread. The publishing house of Berger-Levrault was especially active. Whether beautifully printed in pochoir or cheaply printed on wood-pulp paper, many works encouraged children to support the righteous cause.

Charlotte Schaller[-Mouillot]. Paris: Berger-Levrault, [1914]

On loan from a private collection

In En guerre! (At war!), the first of two children's books on the war written and illustrated by Schaller and published during the conflict, Boby, his two sisters, and the neighborhood children act out the first months of the hostilities. Our hero, astride his rocking horse, immediately mobilizes all his toy soldiers. Boby admires the bravery and heroism of the Belgians. One illustration, anticipating Surrealism, enacts the battle of Liège. The Belgian army, tiny black figures less than one inch high, wages a futile assault on a pair of Prussian boots that dominate the entire landscape and sky.

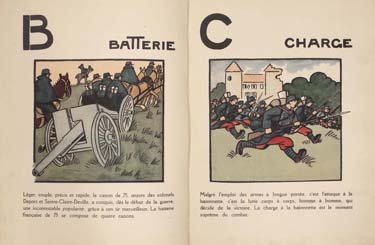

André Hellé. Paris: Berger-Levrault, [1916]

On loan from a private collection

André Hellé's wooden toys of 1911 and his book illustrations, which they populated, certainly inspired children's books on the war in which toys participated in the conflict. Hellé's alphabet took the conflict out of the playroom. The sequence begins with A—Alsace—and ends with Z, for Zouave, who, he assures his young readers, fights with great bravery, and does not exist simply to be the final letter in an alphabet book. In between, such pairings as "Batterie" and "Charge" made the war vivid and, critics asserted, appealing to children. At least one adult found this acceptable fare: in 1916, a fond uncle inscribed this volume to his two nephews.

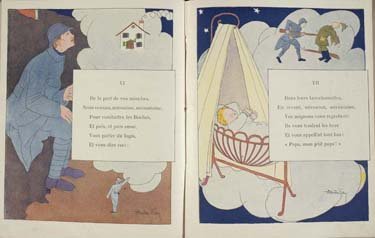

André Alexandre. Illus. by André Foy. [France]: La Renaissance du Livre, [n.d.]

On loan from a private collection

The mise-en-scène of this volume takes place in the space of dreams. Sitting in his trench the soldier thinks of home, with its ivy running around the door and the smoke of a warm fire billowing from the chimney. The baby dreams of his father off killing Germans. It is the father who is now in need of succoring—the baby calls him "My little father!" The illustrations, exploit simple forms and broad passages of color. Thanks to the assistance of toy soldiers who come to life at night in the nursery and magically travel to the front, the Germans are defeated, and the father of this baby in his cradle survives.

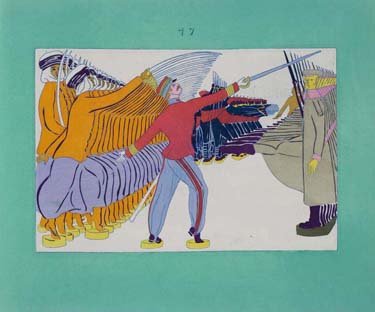

Val-Rau. Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1916

Historical Children's Book Collection

Through the agency of children and their toys, this book tells of the valor and commitment of the French colonial regiments: the Spahis, recruited primarily from Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, and the Tirailleurs, from Senegal and other French possessions in West, Central, and East Africa. Both groups saw extensive service on the western front. The extraordinary palette and the power of the compositions make this work exceptional. Note in this illustration the rhythm of the curved blades of the Spahis led by their French commanding officer, swords raised against the goose-stepping German troops, their purple boots contrasting with the light purple pantaloons of the Algerians.

H[enri] Gazan. Paris: G. Boutitie, 1919

On loan from a private collection

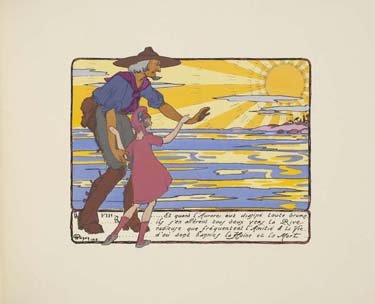

Using a format of comic-book cels, interspersed with full-page illustrations, Marie-Anne et son oncle Sam, with text in English and French, and brilliantly colored pictures, tells the story of little Marie-Anne, the personification of France, who is stranded in the water, threatened on all sides by sharks and horrific sea creatures such as a giant octopus. To her rescue comes the tall, strapping Uncle Sam, identifiable by his white hair and beard, dressed in an American uniform. He defeats her enemies. The final illustration depicts them going together, facing a brilliant sunrise, "where dwell Friendship and Life . . . from which are banished Hatred and Death."

L'oncle Hansi [Jean Jaques Waltz]. Paris: H. Floury, 1919

Historical Children's Book Collection

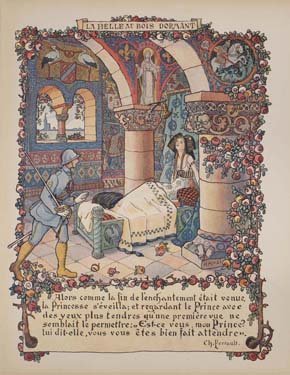

An unabashed promoter of French Alsatian culture, "Hansi," who had worked as a translator during the war, celebrated the return of Alsace to the French after the war in a series of illustrated books. One picture that departed from his usual playful satire is "La belle au bois dormant." Charles Perrault's Sleeping Beauty, wearing the traditional Alsatian headdress, awakes in a bed decorated with the French cock. Above her head Sainte Odile, patron saint of Alsace, and Saint Georges killing the dragon have guarded her long sleep. A brave French soldier is her "prince."

Louise-Andrée Roze. Illus. by Henriette Damart. Paris: Berger-Levrault, [n.d.]

On loan from a private collection

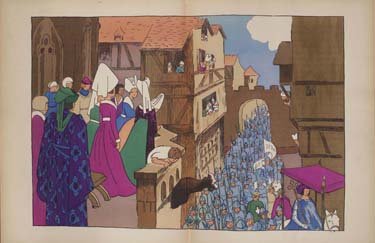

Using bright unmodulated colors and simplified forms reminiscent of the stained glass depicted in the book's pages, Damart's illustrations join Roze's text to tell the story of the great French cathedral of Reims, from the work of stonemasons carving the Smiling Angel, to the church's use for the coronation of French kings. The blue-helmeted soldiers accompanying Charles VII prefigure the poilus retaking the city from the Germans in World War I. Another image shows blood flowing from the body of the stone angel, destroyed by the Germans. Finally, however, whether desecrated or restored, the soul of the cathedral remains, a living testimony to the triumph of faith against brutality.

Marcel Jeanjean. Paris: Hachette, 1919

Historical Children's Book Collection

Image permissions: ©2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

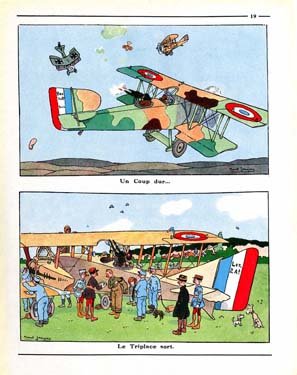

The heroic pilot of Jeanjean's Sous les cocardes represents France. Thus, he flies symbolically under the blue, white, and red of the tricolor circular cocarde. But he literally flies under it as well: it decorates the wings of his plane. World War I was the first in which aircraft were used extensively, mostly for reconnaissance. But in 1914 the French were the first to fire a machine gun from a plane. Children in postwar France must have been thrilled to identify with the exploits of the masters of this new machine and their role in the victory.

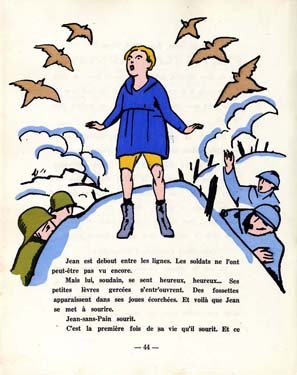

Paul Vaillant-Couturier. Illus. by Picart le Doux. Paris: Clarté, 1921

On loan from a private collection

For the French victors, few books of any kind condemned the war, especially after the armistice. The antiwar children's book Jean sans pain is an exception. The color illustrations recall Charles Martin's in Sous les pots de fleurs in 1917. For example, Picart le Doux depicted bodies in a barren landscape of broken and twisted barbed wire. Jean endures more than hunger. In the cold, his teeth chattering, he sees the degradation of war. A hare that accompanies him answers a query about how long the war will last: miles and miles and years and years.

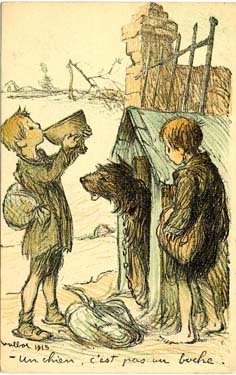

Francisque Poulbot. [S.l.: s. n., 1915]

Rare Book Collection, Gift of Neil Harris and Teri J. Edelstein

Image permissions: ©2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

At least twenty thousand different postcards were printed in France during World War I. They were sent to combatants and posted by soldiers back to loved ones. The collecting began almost immediately and some were certainly displayed. Themes included scenes of battle or sometimes just the name of the conflict or the destruction of war, flags and other patriotic symbols, the camps where the men resided, heroes, comic takes on the life of soldiers, the inevitable pretty girls. A subset of almost all these categories featured children. Francisque Poulbot alone created at least one hundred images of his signature waifs during the Great War.