Enemies

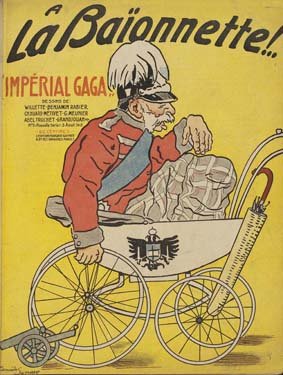

One way of uniting everyone in the country was to make the foes of France vivid to soldiers and citizens alike. The Central Powers were mocked, vilified, and satirized. The Germans received most of the attention—the pointed pickelhaube helmet became a common symbol for them. Franz Josef, emperor of Austria and king of Hungary, is represented as being in his dotage in La baïonnette's "Impérial gaga." And, the Ottoman Empire allowed illustrators to include a touch of the exotic.

Tancrède Synave. La baïonnette, 5 août 1915. Paris: L'Edition Française Illustrée.

Rare Book Collection

Published weekly from July 8, 1915, until April 22, 1920, for an initial price of twenty centimes, the satirical magazine La baïonnette conveyed its take on the war visually, with no photographs and very little text. In its initial appearances, La baïonnette exemplified the expression "Keep your friends close and your enemies closer." The first issue was entitled "Le kaiser rouge," and all the numbers that immediately followed were devoted to a satiric examination of the enemy, an ongoing preoccupation. A sample of titles will demonstrate: "Le clownprinz," "Têtes de Turcs," "Bouillon de kultur" or their depiction of the Austro-Hungarian emperor in ""Impérial gaga."

Paul Iribe. La baïonnette, 13 avril 1916. Paris: L'Edition Française Illustrée.

Rare Book Collection

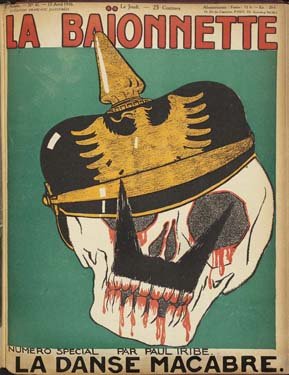

Paul Iribe was unquestionably the most powerful contributor to La baïonnette, represented by covers and numerous illustrations. One special number, "La danse macabre," devoted exclusively to images by Iribe, was reissued in a luxury edition of 380 copies sold separately from the magazine. Its cover was far more graphic than the usual cover of the magazine. And this continued in the contents where Iribe depicted German soldiers murdering innocent women accompanied by an encouraging skeleton. Blood permeates the images: dripping from a nude female corpse tied to a pole, in waves behind a naked murdered woman, or as a literal sea.

Paul Iribe. La baïonnette, 22 juin 1916. Paris: L'Edition Française Illustrée

Rare Book Collection

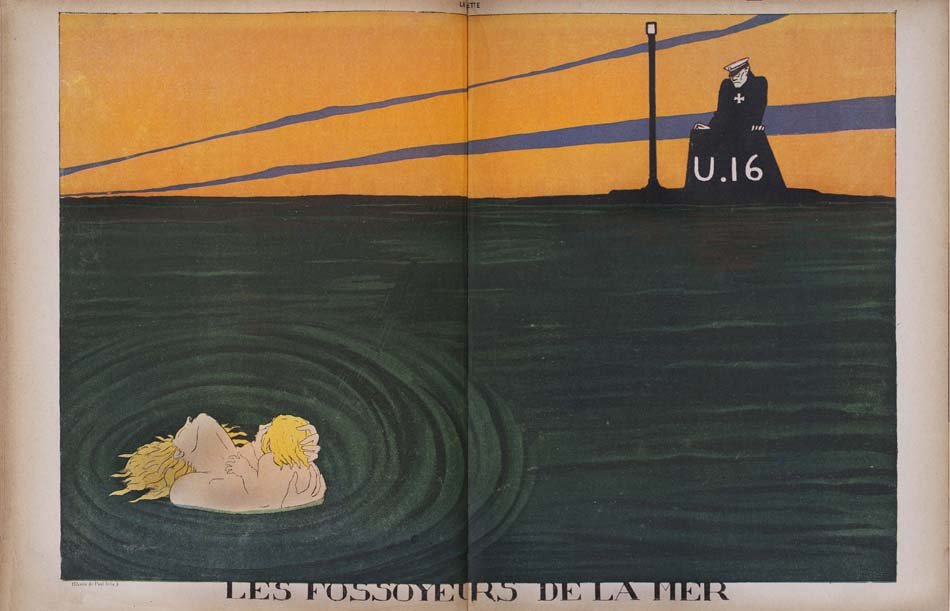

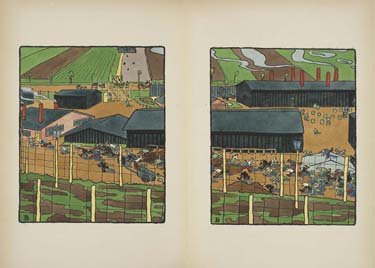

The centerfold of each issue of La baïonnette featured a two-page graphic, and Iribe contributed a disproportionate share of these. A protagonist from his 1908 Les robes de Paul Poiret wandered into one but the searing power of most of his creations belied Iribe's association with fashion. His centerfold for the issue, "Les pirates," with a cover by Cappiello, "Les fossoyeurs de la mer," depicting the "pirate" U-boats, exemplifies his stark, commanding compositions, his exploitation of large visual masses, and his palette of few colors.

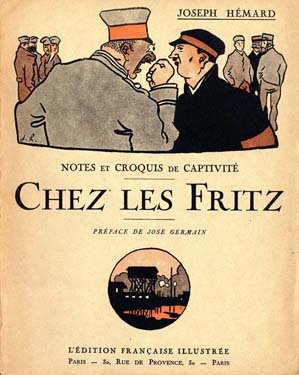

Joseph Hémard. Paris: l'Edition Française illustree, 1919.

Rare Book Collection, Gift of Neil Harris and Teri J. Edelstein

Image permissions: ©2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Hémard documented his years as a prisoner of war from October 1914 until December 22, 1918. The keen observation of human nature, the humor, and the dynamic shorthand that are so prevalent in his later career are already much in evidence. He classified his fellow prisoners: the differences between Russians from Moscow and those from the Caucasus, the variety of sports and activities that occupied the men, the many different poses the spectators could assume, the diversity of his compatriots, who included, to name a few, Arabs, Senegalese, Serbs, Italians, and Japanese — a true gathering of the Allies.

Mario Meunier. Illus. by E. L[ucien] Boucher. Paris: Marcel Seheur, [1920].

On loan from a private collection

The lively action and cheerful colors in the frontispiece of Boucher's record of his tenure in a German prisoner-of-war camp give no inkling of the subject and tone of the images that reside within. In his preface Mac Orlan aptly calls them beautiful images both melancholic and sardonic. They capture the unending boredom and depression of imprisonment with purposefully simple compositions. Even the muted colors echo the inmates' despair and Meunier's brief evocative texts read like prose poems. What this image does share with the interior illustrations is the combination of large blocks of color, oblique angles, and abstracted forms that clearly owe something to Japanese prints and avant-garde practice