Peace

November 11, 1918 brought an armistice. Peace would come with the Treaty of Versailles, signed six months later, but it was a peace that attached to bitter memories. France alone had suffered more than six million casualties. Victory and religion could each offer some solace, and illustrators invoked both as they sought to comfort the bereaved.

Jean Leprince. Paris: L. Arnault, [1918]

On loan from a private collection

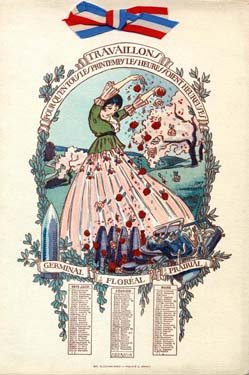

Each three-month page of this calendar has a pochoir illustration surmounted by a wish to work for peace related to each season. The calendar, employing the names of months coined during the French Revolution, is strangely prescient: on the first page a woman drops roses on shells and armaments—and the fourteen-point peace program was announced by President Wilson on January 8, 1918. Next, a woman bars the path of a tank—and a major German offensive occurred in April. The third depicts a woman reacting in horror to an aerial bombardment—and the second battle of the Marne took place in July. Finally, a woman waves an olive branch in front of a burning building—and the armistice was signed on November 11.

Robert Burnand. Illus. by Eduardo García Benito. Paris: Berger-Levrault, [1918]

Encyclopaedia Britannica Collection of Children's Literature

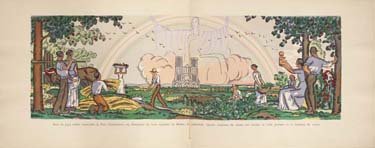

Reims: La cathédrale depicts many moments in the storied history of the iconic building. In the final scene, after all of its triumphs and vicissitudes, the cathedral and its angel preside over a bucolic paradise of peace. A rainbow frames the cathedral, while the spirit of the angel fills the sky. The landscape is filled with a happy family and a rose-covered home, as well as a bountiful harvest. This scene brings to mind Benito's print La belle terre, for the publisher Grasset. There, the arriving heroic American troops even help harvest the wheat.