Literature

“Agriculture is much followed among them; there is not a span of earth without cultivation, and they observe the winds and propitious stars. […] They do not kill willingly useful animals, such as oxen and horses. They observe the difference between useful and harmful foods, and for this they employ the science of medicine.”

“The sun is the father, and the earth the mother. The sea is the sweat of earth, or the fluid of earth combusted, and fused within its bowels, but is the bond of union between air and earth, as the blood is of the spirit and flesh of animals. The world is a great animal, and we live within it as worms live within us.”

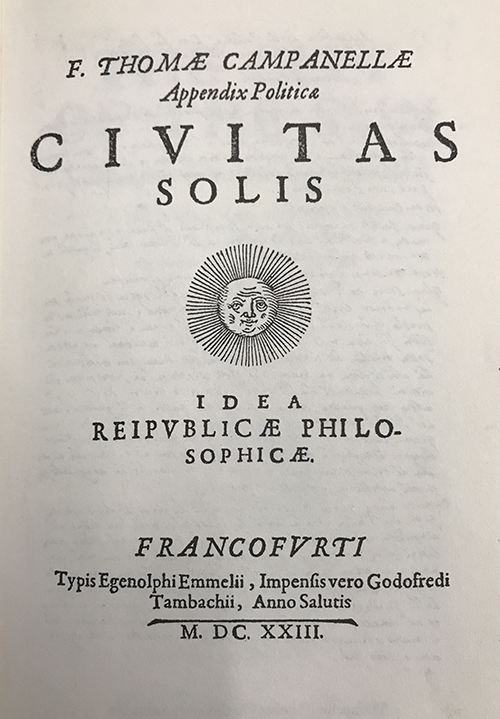

Tommaso Campanella

Written by a Dominican friar in prison and published in 1602, this philosophical work in the form of a dialogue describes an ideal commonwealth governed by principles such as community of goods, division of labour, and equal dignity for all men. Private property, undue wealth, and poverty do not exist in his ideal city, for no man is permitted more than what he needs. The author imagines a society that lives in a harmonious state close to nature. During his life, Campanella was involved in pansensism, the doctrine that all things in nature are endowed with sense, and in panpsychism, the view that all reality has a mental aspect. This philosophical approach justifies his belief that nature had to be respected and regarded as an ideal model for any political organization.

“Agriculture is much followed among them; there is not a span of earth without cultivation, and they observe the winds and propitious stars. […] They do not kill willingly useful animals, such as oxen and horses. They observe the difference between useful and harmful foods, and for this they employ the science of medicine.”

“The sun is the father, and the earth the mother. The sea is the sweat of earth, or the fluid of earth combusted, and fused within its bowels, but is the bond of union between air and earth, as the blood is of the spirit and flesh of animals. The world is a great animal, and we live within it as worms live within us.”

“There we shall hear the chant of birds, have sight of verdant hills and plains, of cornfields undulating like the sea, of trees of a thousand sorts; there also we shall have a larger view of the heavens, which, however harsh to usward yet deny not their eternal beauty; things fairer far for eye to rest on than the desolate walls of our city. Moreover, we shall there breathe a fresher air.”

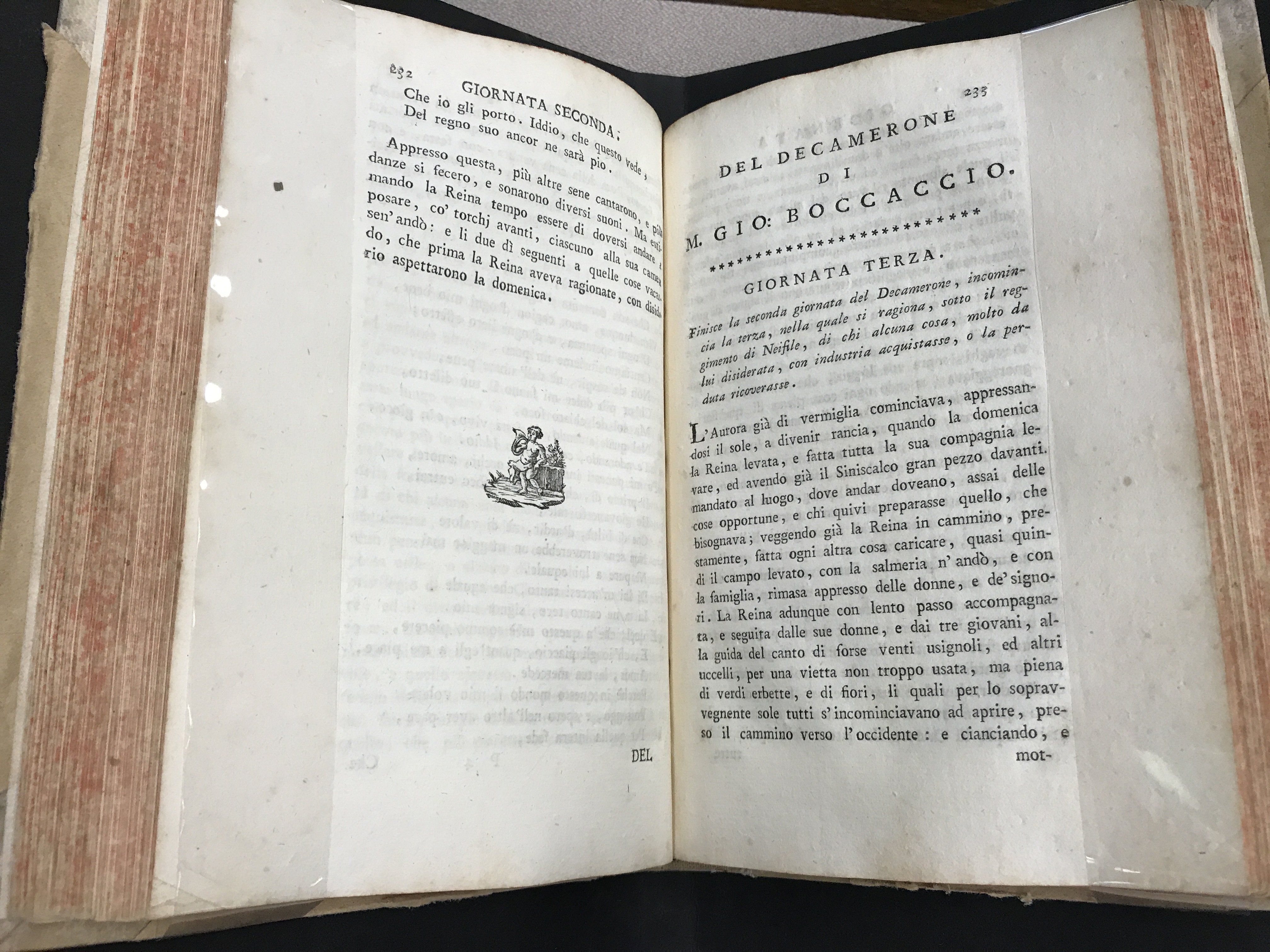

Giovanni Boccaccio

Written in the wake of the Black Death of 1348, Giovanni Boccaccio masterfully constructs an ideal society and its mores. The brigata, made of ten young noble women and men, moves in the country outside the city of Florence, seeking to escape the ravages of the plague. Here, through the experience of storytelling, they establish a new social and moral order in a perfected natural environment. A direct contact with the natural world is described as essential, since it provides them with the necessary means to face the city again and to potentially shape there a perfected form of social existence. Nature is considered a haven of security, of health, of moral excellence. Being in harmony with the environment is one of the main principles that will grant a material and spiritual rebirth.

“There we shall hear the chant of birds, have sight of verdant hills and plains, of cornfields undulating like the sea, of trees of a thousand sorts; there also we shall have a larger view of the heavens, which, however harsh to usward yet deny not their eternal beauty; things fairer far for eye to rest on than the desolate walls of our city. Moreover, we shall there breathe a fresher air.”

“They cultivate their gardens with great care, so that they have both vines, fruits, herbs, and flowers in them; and all is so well ordered and so finely kept that I never saw gardens anywhere that were both so fruitful and so beautiful as theirs. And there is, indeed, nothing belonging to the whole town that is both more useful and more pleasant. So that he who founded the town seems to have taken care of nothing more than of their gardens.”

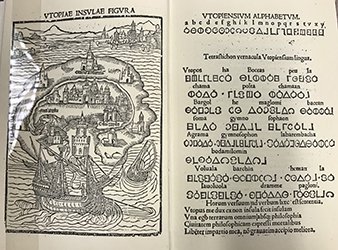

Thomas More

The inventor of the term Utopia sketches in this 16th century masterpiece, originally written in Latin, a perfect and imaginary state while subtly expressing sharp criticism of the English society of his time. A variety of subjects are discussed, most famously social justice, religious tolerance and human happiness. However, not only does he analyze the economical, political, and social consequences of implementing his revolutionary ideas, but he is also concerned with their effects on the natural environment. The result is an ecologically responsible society, based on agriculture, that leads a life of moderation and sufficiency. A central element of his ideal society is a responsible attitude towards nature, thanks to a prudent use of resources, so that waste problems can be avoided and the environment preserved.

The book presented here is a splendid facsimile reproduction (original size) of the copy published in 1516, today at the British Museum marked C.27.b.30.

“They cultivate their gardens with great care, so that they have both vines, fruits, herbs, and flowers in them; and all is so well ordered and so finely kept that I never saw gardens anywhere that were both so fruitful and so beautiful as theirs. And there is, indeed, nothing belonging to the whole town that is both more useful and more pleasant. So that he who founded the town seems to have taken care of nothing more than of their gardens.”

“Shall I not have intelligence with the earth? Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?”

“Whatever my own practice may be, I have no doubt that it is a part of the destiny of the human race, in its gradual improvement, to leave off eating animals.”

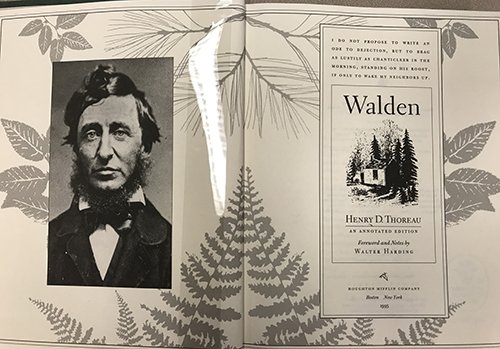

Henry David Thoreau

Known as a politically oriented poet-philosopher and a non-conformist thinker, the American Henry D. Thoreau (1817-1862) established his reputation as a prophet for ecological thought and the value of wilderness, representing a radical version of sufficiency in the history of ecological utopias. In his view, nature is the mother of humanity, a creator of life and beauty. Seeking solitude and self-reliance, he moved to the woods by Walden Pond, outside Concord Massachusetts, where he lived alone for two years in a self constructed cabin before returning to society.

Through his example, he sketches an alternative society and depicts a lifestyle based on a simplification of life, stripped of materialism, so that humanity can return to its deepest core, and recover a more worthwhile happiness in the appreciation of nature. Throughout the book he expresses his concern for the damage caused by current human activities to the natural environment as a consequence of the urbanization of the nineteenth century and the “spiritual poverty” of his contemporaries, who become their own slave masters. He then articulates the idea that humans are part of nature and that we function best, as individuals and societies, when we are conscious of that fact.

The edition here presented is limited to 100 copies for sale in the United States, 750 for England, and 35 presentation copies.

“At night we sleep; in the morning we bathe; we eat when we are hungry, converse when we feel inclined, and on most days labour a certain number of hours. But more than these things, which have a certain amount of pleasure in them, are the precious moments when nature reveals herself to us in all her beauty. We give ourselves wholly to her then, and she refreshes us; the splendour fades, but the wealth it brings to the soul remains to gladden us.”

William Henry Hudson

British author, naturalist, and ornithologist, William H. Hudson grew up on the Argentinean Pampas and then fell in love with Patagonia, where he traveled to study the birds. As a response to industrial development, the utopian vision of this novel published in 1887 centers on harmonious appreciation of nature. A traveler recounts in the first person of an idyllic society and of his struggles to adapt to it. The rich descriptions of the peaceful lifestyle of working with hands, following a vegetarian diet, and celebrating holidays based around nature, provide a beautiful example of a possible reality that can be read as an anticipation of modern ecological mysticism.

“The nearer we came to the house, the greater we found the profusion of flowers which ornamented every field. Some had no other defence than hedges of rose trees and sweetbriars, so artfully planted, that they made a very thick hedge, while at the lower part, pinks, jonquils, hyacinths, and various other flowers, seemed to grow under their protection. Primroses, violets, lilies of the valley, and polyanthuses enriched such shady spots, as, for want of sun, were not well calculated for the production of other flowers. The mixture of perfumes which exhaled from this profusion composed the highest fragrance, and sometimes the different scents regaled the senses alternately, and filled us with reflections on the infinite variety of nature.”

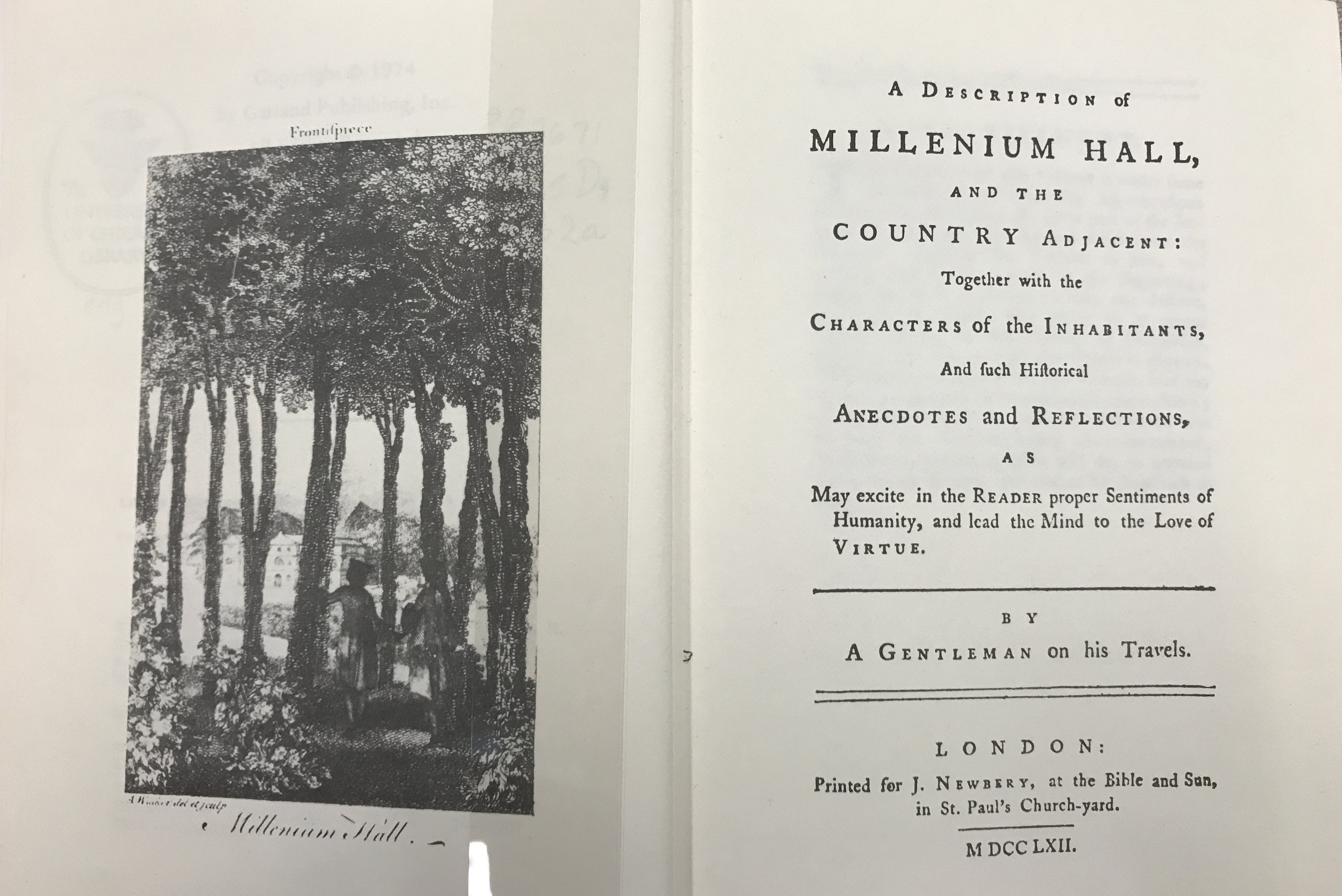

Sarah Scott

This central document of the British Enlightenment, published in 1762, describes a utopian society of women living autonomously. As a response to a courtly and patriarchal gentry, and as a critique of the London city space affected by dissipation, Sarah Scott gives birth to a unique form of ecofeminism that functions as a refuge for women who are victims of the gender system, in a bucolic country estate that recalls the arcadian pastoral tradition. The beauty of the grounds is what immediately captivates the narrator as she first approaches Millenium Hall. She also describes an animal sanctuary in which humans are not tyrants over animals, and uses Alexander Pope’s words about Eden to reinforce the fact that the animals were protected from meat eating.

“But what matters most is the aspiration to live in balance with nature, "walk lightly on the land," treat the earth as a mother.”

Ernest Callenbach

This 1970s cult novel, and hopeful antidote to the environmental concerns of today, was born out of the political and economic turmoil of those years and became a pioneer of the growing environment movement. Ecotopia is the name of a new “stable state” in the novel, founded when parts of the American Northwest seceded from the Union to create a new country and ecosystem that incarnates the perfect balance between human beings and the environment. The novel takes place in 1999, twenty years following the formation of Ecotopia, and consists of reports and diary entries of the first American invited to visit and report on Ecotopia. Interest in Ecotopia stems largely from the possible social and political arrangements it describes, in the creation of a society that is founded on principles such as sustainable agriculture, democracy, localism, and mutual support, emphasizing the interconnectedness among humans and nature and the balance between economic pursuit and ecological concern. An important theme in Ecotopia is also recycling. In fact, the communities depicted re-use everything they can and do not produce excessive waste.

“A forest ecology is a delicate one. If the forest perishes, its fauna may go with it. The Athshean word for world is also the word for forest.”

Ursula LeGuin

Set several centuries in the future, and part of Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle, the novel is particularly relevant to our own actions today regarding the environment, the destruction of our planet’s natural resources and assimilation of indigenous peoples. Men from Earth have arrived on the planet Athshe, renamed it New Tahiti, and are in the process of logging the abundant forest, sending the valuable timber back to a homeworld which has suffered environmental destruction. The native Athsheans are small, green-furred creatures who live in natural harmony with their world. They have a matriarchal society and have no history of violence prior to the arrival of humans.Their world is described in rich detail and shows Le Guin’s talent for worldbuilding. Athshean culture is thoroughly integrated with the planet’s ecology. Rather than clearing the forests, the Athsheans live within the roots of the trees themselves in widely dispersed clans that are named after tree species.

“We’re using up the Earth. It’s almost gone.”

Margaret Atwood

This ecotopian novel, published in 2009, contains visions of a negative and dystopian future that connects with a range of environmental issues. Set in a post-apocalyptic western nation, the book follows the fates of two female survivors of the disaster that wiped out Earth. Central to the plot is a religious sect, the Gardeners, who have strong ecological concerns and believe in living according to the laws of nature. Their eating habits and clothing is determined by a certain code that is totally in terms with nature, they grow their own vegetables, avoid television and computers.

The Canadian author, one of the most acknowledged feminist novelists, makes a clear critique of modern men, with their egotistical ambitions, and depicts them as perpetrators and as the worst catastrophe the world has ever seen. Through this dystopian novel, she warns her readers as to what might happen if the indifference towards the abuse of nature goes on.

The copy of the book owned by the Regenstein Library is signed by the author and dedicated to the University of Chicago students.