Germany Goes to the Ghetto: German-Jewish Soldiers on the Eastern Front

The plight of East European Jewry acquired greater political urgency during World War I as German-Jewish soldiers on the eastern front discovered the immense suffering and squalor in the ghettos. Though most German Jews supported the fatherland in the war, physical contact with the Ostjuden challenged established national loyalties and personalized what for many had been an abstract matter. The inaugural issue of Buber's journal Der Jude contained numerous expressions of concern for the Ostjudenfrage. Jewish journalists and writers stationed in the East described the devastating effects of the war on East European Jewish life while those in Germany wrote about the grim situation on the home front. Though German Jews had long opposed mass settlement of Ostjuden in Germany, many were outraged by the anti-Semitic rhetoric that accompanied the new policy of Grenzschluss (border closing), which curtailed the entry of Jewish refugees.

Solidarity with the Ostjuden often betrayed antipathy toward the bourgeois values of liberal German society. Whereas the previous generation of German Jews expressed shame over their eastern counterparts, their own children were embarrassed by the materialism of their parents and looked eastward for a source of renewed pride. This "cult of the Ostjuden" criticized both assimilated Jews and Western Zionists who flirted with East European Jewish culture as an abstraction but remained estranged from the reality of their own people.

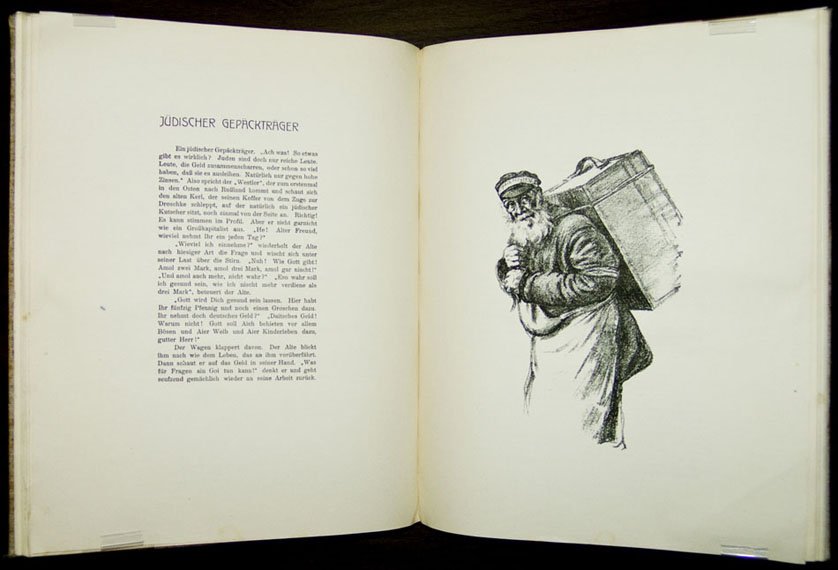

Hermann Struck, (1916), Rosenberger 27-150.

While stationed on the eastern front, Struck and Eulenberg composed these sketches and accompanying text to expose a German audience to Jewish life in the easternmost region of the Russian Empire. The image of the honest Jewish porter is intended to dispel stereotypes of the wealthy Jewish moneylender and capitalist parvenu. In the preface, the authors proclaim their allegiance to Germany.

Arnold Zweig and Hermann Struck, (1920), Rosenberger 25-157.

Zweig portrayed East European Jewry in mythic terms as the living embodiment of an authentic Jewishness upon which Zionist renewal was to be built. Addressing the contentious issue of Jewish prostitution, he hoped to salvage the respectability of the archetypal East European Jewish girl by presenting her as "the victim and symbol of our European situation."

Nathan Birnbaum, (1915) Rosenberger 247-63.

Birnbaum criticized cultural Zionists for offering a romanticized vision of the Ostjuden that overlooked their present reality. Though he coined the term "Zionism," Birnbaum broke with the movement and turned instead to Yiddishism and Diaspora Nationalism, making the retention of East European Jewish culture his central aim. He served as an organizer of the 1908 Czernowitz Conference, which promoted Yiddish as a national Jewish language.

"Die Ostjudenfrage," in Ost und West (1916), No. 2 (February 1916): 73 [Online].

The journal Ost und West ("East and West") promoted a Jewish ethnic identity by transferring the negative stereotype of the Jewish parvenu long associated with East European Jews to assimilated German Jews who had forsaken their Jewish identity.