"New Jews" vs. "Old Jews": Emancipation, Assimilation, and the Ostjuden as Other

Jewish emancipation was a slow and uncertain process in Germany, dragging on from the Prussian Edict of Toleration of 1812 until the consolidation of the German Republic in 1871. Even the most "enlightened" supporters of the cause assumed that the Jews could attain full civil rights only after having achieved intellectual and moral improvement. German Jews, seeking to prove their commitment to the fatherland, dissolved traditional notions of Jewish nationhood and worked to acculturate into the educated middle class, or Bildungsburgertum.

Assimilation produced a distinction between the "new" assimilated German Jew and the "old" Jew of Eastern Europe. The ghetto Jew stood for the characteristics of Jewish culture to be supplanted by German Sittlichkeit (morality and refinement). Thus, the caftan was discarded in favor of the cravat, and Yiddish was derided as a vulgar German dialect. Moses Mendelssohn, the chief spokesman of the Jewish Enlightenment, described this so-called "jargon" as "a language of stammers, corrupt and deformed, repulsive to those who are able to speak in a correct and elegant manner." Proponents of Wissenschaft des Judentums (The Science of Judaism) who sought to reform Jewish education and worship replaced the tradition of talmud torah (religious study) with the German ideal of Bildung (secular education and self-cultivation).

In popular literature, so-called "ghetto stories" offered a romantic yet patronizing view of East European Jewish life. Their authors were liberal enlighteners whose sympathy for East European Jews was mixed with criticism of their religious obscurantism. Many of these stories portray East European Jews who strive to achieve intellectual and cultural sophistication through German Bildung.

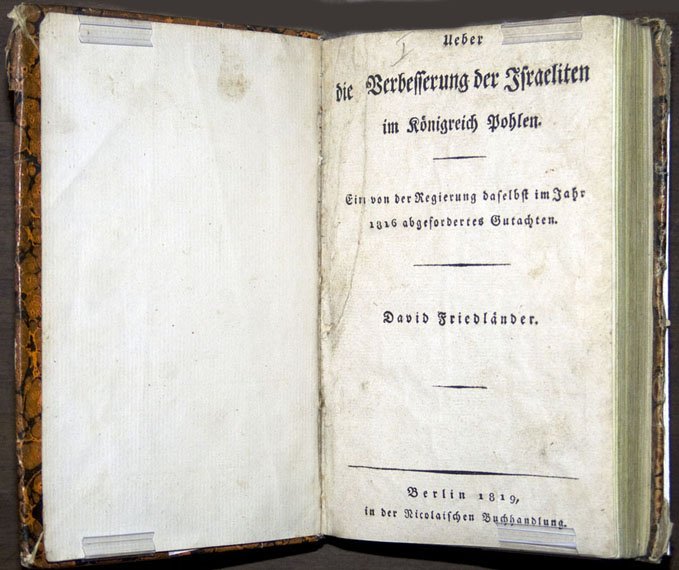

David Friedländer (1816), Rosenberger 216B-10A.

David Friedländer associated Poland with Hasidism, mysticism and the irrational, which he believed violated the "religion of reason" emerging from the German Enlightenment. In this work, he describes Polish Jews as "the most cloddish and unrefined class of human beings. In terms of culture and morality they stand on the lowest level next to wild animals."

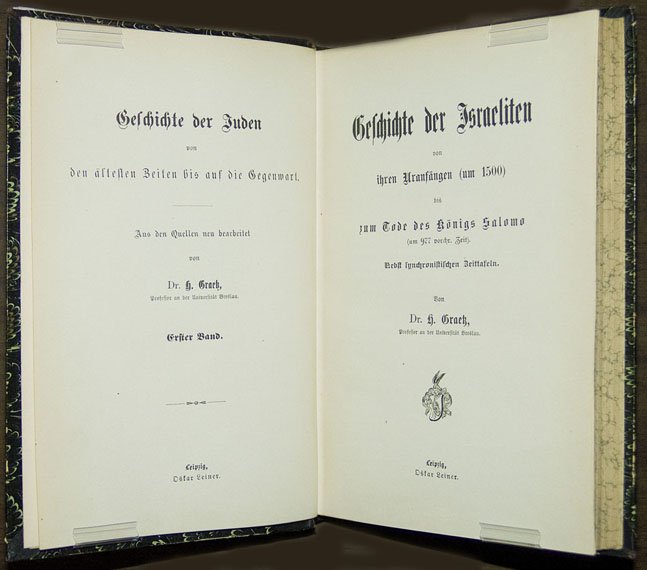

Heinrich Grätz, (1888-1900), Rosenberger 65A-2.

Grätz's History of the Jews exemplifies the scholarly focus of Wissenschaft des Judentums, which contrasted German Bildung with the "irrational" Hasidism of Poland and the "superrational" Talmudic discourse of the Lithuania. Grätz refused to allow his book to be translated into Yiddish, which he called a "half-bestial language."

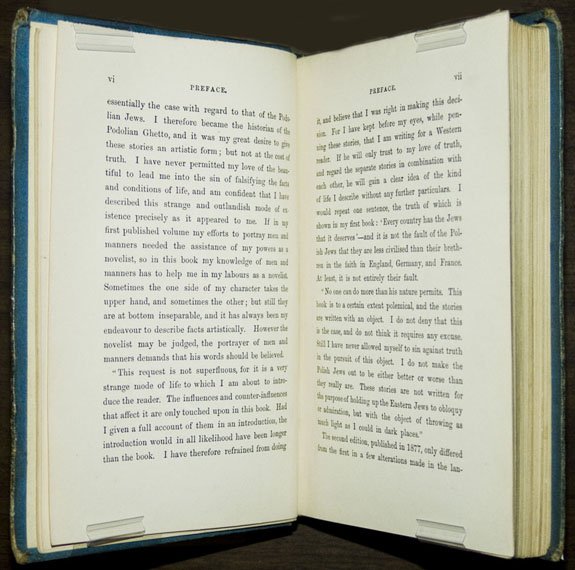

Karl Emil Franzos, (1883), Rosenberger 40-14.

Franzos referred to Eastern Europe as Halb-Asien (Half Asia), a world of squalor and superstition. His satirical depiction of fictional Barnow, based on his own Galician hometown, blames the indigence of Polish Jewry on the callousness of the Polish authorities. Franzos viewed German Kultur as the solution to the economic and social problems of Polish Jewry.

S.J. Agnon, "Aufstieg und Abstieg," in Der Jude (1924), No. 1: 38 [Online].

Buber published many German translations of literature by East European Jews in his journal Der Jude ("The Jew"), including the pseudo-midrashic tales of S.Y. Agnon, the Galician-born Hebrew writer. Buber saw Agnon as the quintessential "New Jew": "Galician and Palestinian, Hasid and pioneer — in his true heart he carries the essence of both worlds in the equilibrium of consecration." The story Aufstieg und Abstieg ("Ascent and Descent") was translated into German by the philosopher and historian Gershom (Gerhard) Scholem.