The Future’s Style

Every Soviet child was destined to live in a world that did not yet exist, a world very different from the one familiar to the adult Soviet illustrators.[1] With the harrowing and tumultuous experiences of war, revolution, and reconstruction still recent memories, artists engaged in the production of Soviet children’s books during the 1920s and 1930s inhabited a paradoxical creative environment: the child-reader could not be shown the world as it is, or as it really was, but only as it will be. The child had to be imagined as a traveler biding time in the same visual universe as the illustrator, yet the laws of history had already decreed that the young Soviet citizen would soon move on to the future. Therefore, any truly “Soviet” children’s illustrations needed to find a way to exist simultaneously on several different planes of experience.

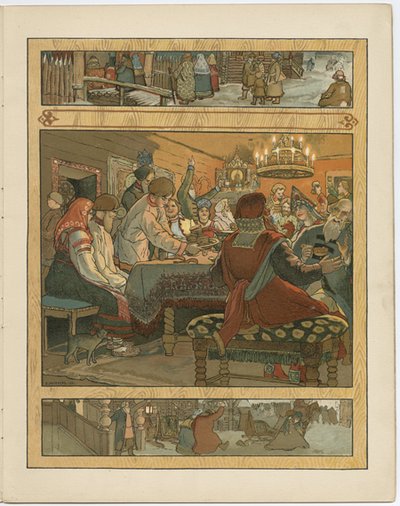

Illus. by Ivan Bilibin. Moscow: G.E. Lissner, 1902.

In such a collectively anticipatory atmosphere, the children’s illustrations of famed pre-revolutionary artists, such as Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942), could serve only as negative examples for the aspiring designer. Throughout the early Stalin era, Bilibin’s evocative, elaborate graphic ensembles seemed inherently backward-looking, hostile to the future-oriented disposition of a vital, resourceful reading public. Such ornate, yet tastefully rustic illustrations offered nostalgic pictures of a primitive Russian past, a mental and physical space destined for oblivion in the technologically advanced Soviet state. As such, the traditional visual register of Russian children’s books (comforting and comfortable pictures of cuddly creatures, cozy cabins, and picturesque forests) simply had no place in the new representational order.

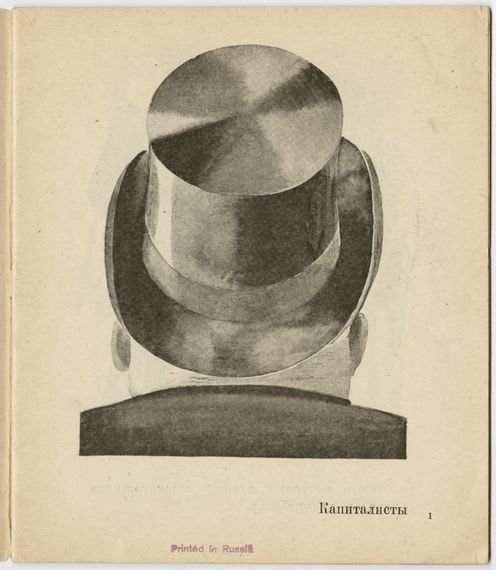

Rather than fleshing out such themes, the Soviet illustrator learned to place a protagonist’s activities in a kind of empty space, a zone dominated by boldly-rendered figures acting within an expanse of immaterial whiteness. Thus, perhaps the most obvious stylistic transformation in Soviet children’s books revolves around the appearance (and gradual disappearance in the years before and after World War II) of the blank spaces that typically surround a book’s principal “action.” In illustrations such as those of Nikolai Denisovskii’s in Zoloto (Gold) and Bei v Baraban! (Bang the Drum!) the juvenile reader encounters a radically disembodied world of people and objects lodged in barely imaginable landscapes. By design, such books made it difficult for the child to relate her daily experiences to the illustrations set before her. Similarly, in Aleksandr Deineka’s productions for children, visual relationships emphasize an overwhelming sense of non-belonging: odd perspectives, machine-like shapes, and intense colors define the atmosphere. Such gestures overturn the incorporative, reassuring logic of Bilibin’s graphic work by teaching the child always to expect the unexpected. In this way, illustrations such as Konstantin Kuznetsov’s for Mikhail Ruderman’s Subbotnik (Saturday Work) prod the reader to prepare for the appearance of new visual constellations. These defamiliarizing strategies reached their apex in the children’s literature of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

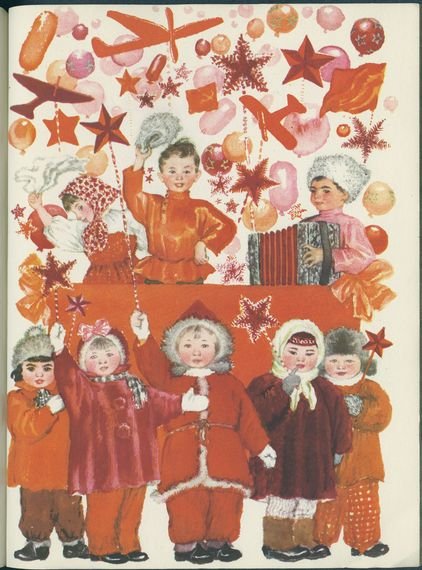

Soon enough, however, a new visual idiom began to emerge, one far more consonant with the pre-revolutionary era. One need only compare the transformation of Vladimir Lebedev’s illustrations between his work in Samuil Marshak’s Bagazh (Luggage) and those he created for Raznotsvetnaia kniga (The Multicolored Book). In the course of those sixteen years, Lebedev abandons the generic, generalizing tone of Luggage for The Multicolored Book’s welcoming grammar of colorful butterflies and luxurious banks of snow. In other words, as the Soviet Union emerges from the traumas of rapid modernization, forced collectivization, and mass purges (not to mention the horrors of World War II), Lebedev emerges from those years of displacement and disturbance a transformed man. His work reflects his change from being an avant-gardist of the first order and a master of Soviet pedagogical minimalism, into a devoted retro-traditionalist. Perhaps the artist had concluded that a renewed rendering of the familiar offered a crucial source of psychic nourishment in a time of troubles, a reassuring voice within the violent cacophony of Soviet mass self-improvement. Throughout the postwar era, these competing styles reappear in the realm of children’s illustration, the soothing images of a nostalgic past resisting the abstracting will of a Communist future.

by Matthew Jesse Jackson

[1.] Boris Groys, “Soviet childhood was the promise of Communism realized. Every child was seen by Soviet ideology as a potential member of a future, better Communist society.” From “Designing the Childhood” in Ilya & Emilia Kabakov Present: Ilya Kabakov, Children's Book Illustrator as a Social Character (Tokyo: Tokyo Shimbun, 2007), 18. Translation slightly altered.

Samuil Marshak. Illus. by Vladimir Vasil'evich Lebedev. Moscow: Gos. izd-vo detskoi lit-ry Ministerstva prosveshcheniia RSFSR, 1947.

© Estate of Vladimir Vasilevich Lebedev/RAO, Moscow/VAGA, New York. vagarights.com

Samuil Marshak. Illus. by Vladimir Vasil'evich Lebedev. Leningrad: Molodaia gvardiia, 1931. 6th ed.

© Estate of Vladimir Vasilevich Lebedev/RAO, Moscow/VAGA, New York. vagarights.com