Mapping and Modeling

Introduction

Upon visiting Moscow in the winter of 1926-27 Walter Benjamin observed, “The map is almost as close to becoming the center of the new Russian icon cult as is Lenin’s portrait.”[1] Maps and other kinds of models not only told Soviet citizens where things were and how they worked, but also served as a propaedeutical device for the vast redesign of the world envisioned by Stalin. It was not unusual for even a book of poetry, like Semën Kirsanov’s Piatiletka (Five-Year Plan), to include a foldout map allowing one literally to plot out the ongoing story of the construction of socialism. In children’s books these devices play a particularly important role of teaching the child to become a model citizen of the new, better order.

Maps

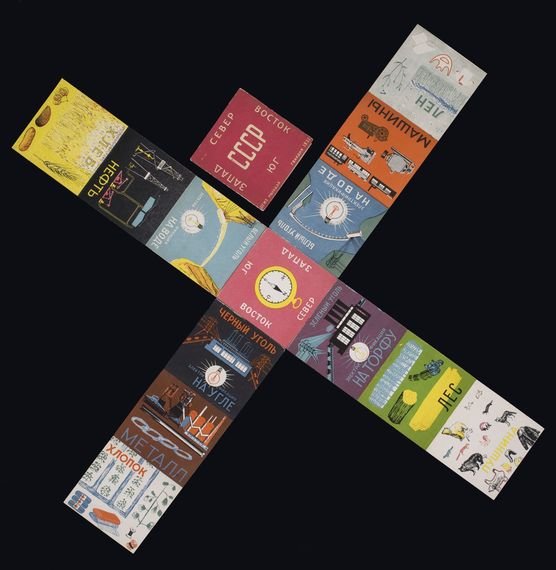

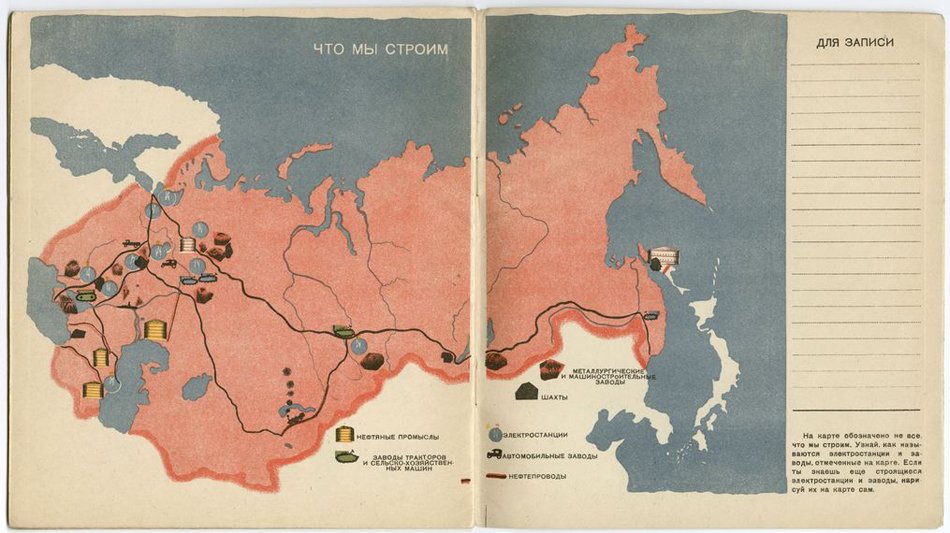

Ekaterina Shabad’s Sever, iug, vostok i zapad (North, South, East, and West) allowed a child to map out the Soviet society and economy by folding it out towards the four points of the compass. The five pictures featured in each direction depict ethnicities, natural resources, industrial products, and livestock. The book Chto my stroim? (What Are We Building?) by Leonid Lipavskii (pseudonym L. Savel’ev) and Vladimir Tambi lists various kinds of construction (including power stations and the Turksib railway), leaving space for children to add more new phenomena as they arise and the children learn about them. The interactive design underscores the point that the Soviet map was fundamentally open-ended and subject to change.

Lipavskii and Nikolai Lapshin collaborated on a book Chasy i karta oktiabria (The Clock and Map of October, 1931), which mainly consists of maps showing the development of the October Revolution (in its Stalinist retelling). At the end of the book these historical maps are compared to the Five-Year Plan, which are the “clock and map” of the new “battle for socialism.” Thus the Soviet map, instead of being merely an account of the present or the past, becomes an account of the future.

Models

Children’s books teach children to build models of objects in the world and aspire to modeling new things that do not yet exist. In his book Otkuda stol prishel? (Where Does the Table Come From?) Marshak concludes by listing the purposes of a table, foremost among which is modeling an airplane:

On it I spread my draft,

And when the time comes,

According to the draft

Build an airplane.

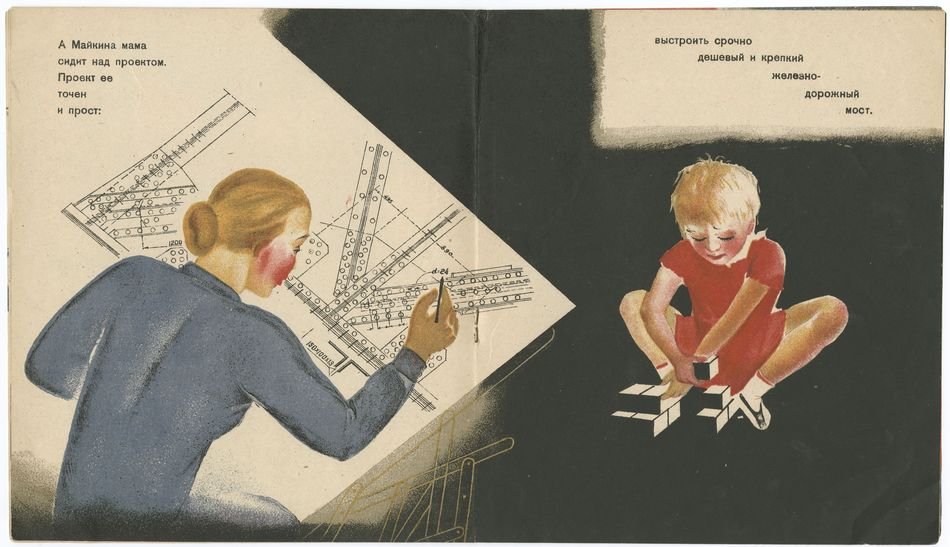

In Nina Sakonskaia’s Mamin most (Mom’s Bridge, Item 5) we witness a variety of professions that have opened up to women, including that of an architect. The labor of projecting a bridge is directly compared to a child playing with building blocks. In this way children and adults collaborate in modeling a new world:

Our mothers

work with us

in our

victorious

nation.

To every, every

working mother

we send

our Octoberite

greeting!

By Robert Bird

Items Discussed in Exhibition:

- L. Savel'ev. Chasy i karta oktiabria. Illus. by N. Lapshin. Moscow: OGIZ, Molodaia gvardiia, 1931. (not pictured)

[1] Walter Benjamin, Moscow Diary, ed. Gary Smith, trans. Richard Sieburth, preface by Gershom Scholem (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1986) p. 51.

Samuil Marshak. Illus. by Vladimir Vasil'evich Lebedev. Moscow: Gos. izd-vo detskoi lit-ry, 1946. © Estate of Vladimir Vasilevich Lebedev/RAO, Moscow/VAGA, New York. vagarights.com