The Collective

Introduction

Theorists of the Russian Revolution placed heavy emphasis on the concept of the collective, both as a tribute to the movement’s populist roots and, looking to the future, a means to stabilize and build a new society from the ashes of the Civil War (1918-1921). Soviet propagandists (or cultural-enlightenment workers, as they referred to themselves) stressed that only with everyone working together could the fledgling state achieve its goals of full industrialization and modernization.

During the Cultural Revolution (1928-1932), cultural-enlightenment workers turned to children’s literature to spread their message of the collective ideal. In part, this was a response to the fact that the children of the first Soviet generation were the first members of many households to achieve literacy. Moreover, it was believed that children, whose minds were uncorrupted by the influences of the previous era, would imbibe the revolutionary gospel of the collective without reservation, then teach it to their elders and, in time, their own children, thus creating a clean break with the past and a firm beginning for the new, collective future.

Work and Recreation

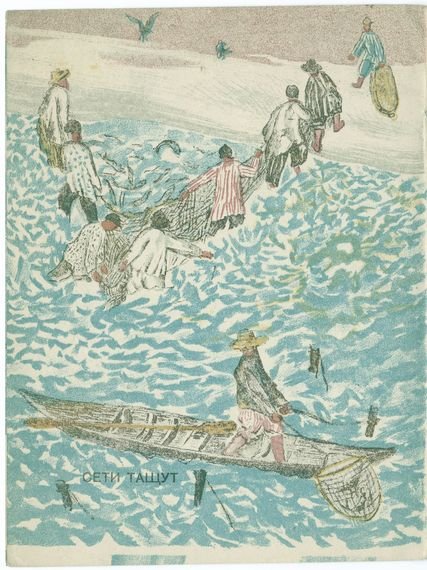

One of the primary assets of the collective was its ability to perform work as a single unit in harmony with itself. As a prime example, B. Inozemtsev’s Za ryboi (Fishing) shows a series of images in which groups of fishery workers work together to bring in the catch, prepare it, and send it off to the cooperative to feed the nation, culminating in a bountiful image of succulent fish ready to eat. In an even purer illustration of the good will created by and further facilitating the collective ideal, the factory workers and children in Mikhail Ruderman’s Subbotnik (Volunteer Work) labor together voluntarily after the workday is done to unload a trainload of potatoes sent to feed the community.

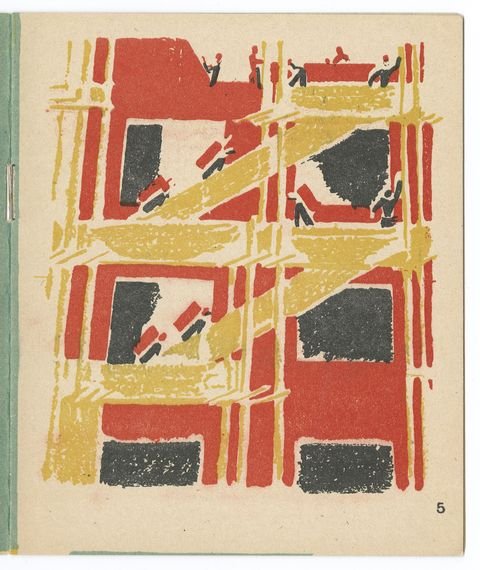

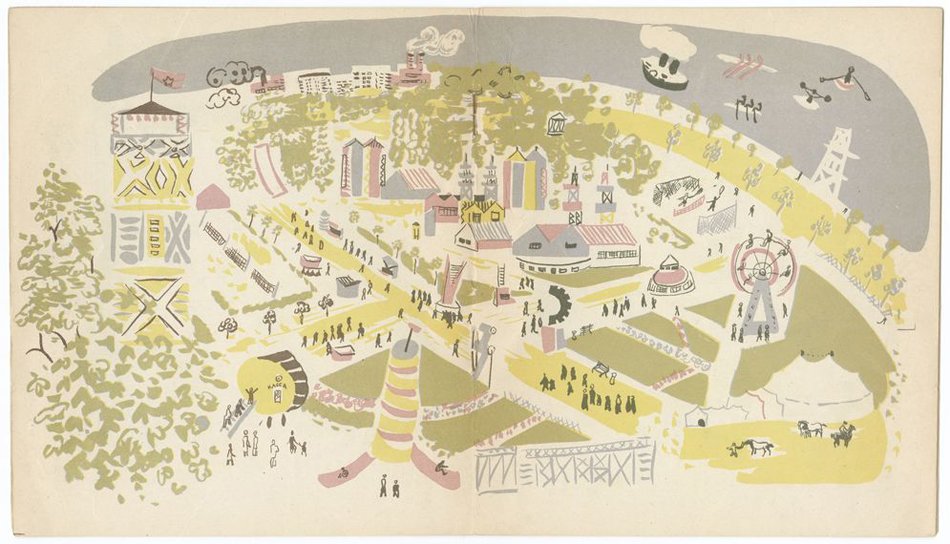

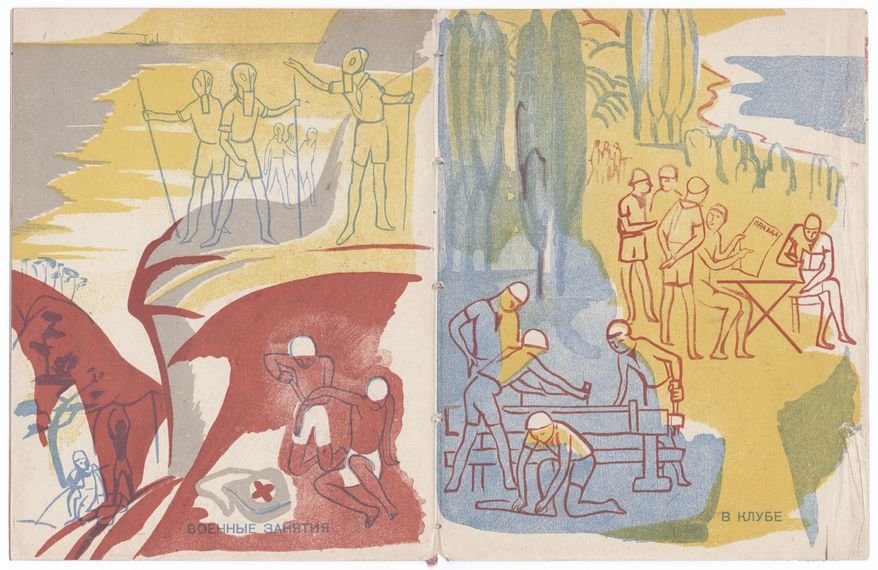

Interestingly, some authors do take account of the reality of specialization within the workplace, though they soften its individualizing tendency by portraying unified brigades performing specific labor tasks together. Perhaps in a sideways nod to Marx’s dictum, “each according to his means,” the brick layers, carpenters, and electricians of Ia. Meksin’s Stroika (Construction Site) are clearly shown laboring as groups within the larger collective whole, working together to bring the new building into being. Vladimir Maiakovskii’s Guliaem (On a Walk) achieves a similar ideal in microcosm. As a young boy walks through town with his nurse, she points out all the different members who come together to form the social collective, including soldiers, workers, peasants, bureaucrats, and members of the Communist Youth League. Finally, Alfeevskii and Lebedeva’s joyously drawn Park kul'tury i otdykha (Amusement Park), teaches that labor is not the only thing that brings the new society together, by depicting the many pleasures available to good workers in their off hours. The book highlights that every one of them chooses to spend those hours of relaxation together, in the truest spirit of the collective ideal, as shown in illustrations bursting with brightly colored, unindividuated bodies.

Participation

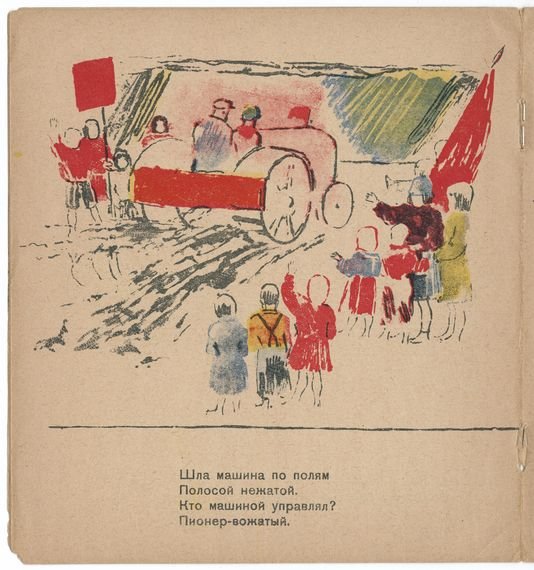

Beyond teaching its audience about the nature and power of the collective, Soviet children’s literature further sought to invite them to actively take part in it. The Pioneer movement, a scouting group for younger children who would later join the Communist Youth League, played a prominent role here. I. Iznar’s Artek (Camp Artek) shows healthy, happy children engaged in the many collective pleasures of Pioneer sleep-away camp, ranging from work and military preparedness to study to unrestrained play. K. Vysokovskii’s Pionery v kolkhoze (Pioneers on the Collective Farm) takes a similar line, while introducing the idea that children, too, can join in the collective labor of society. On a day trip to a collective farm, eager Pioneers distribute school supplies, and then work alongside their elders installing a radio, plowing, sowing, milking and collecting recyclable material. Aleksandr Vvedenskii’s Kolia Kochin (Kolia Kochin) stands out as a fascinating example of a book with just a bit more bite. The title character initially refuses to join the collective, preferring his own incorrect answers to those learned collectively by the others. The text makes clear that such a child will be cast out absolutely from the warmth and camaraderie of the collective, which the others continue to enjoy without further regard for him. Fortunately for Kolia (and all other naughty individualist children), the collective is eternally welcoming to those who surrender themselves to its will. When Kolia finally repents and asks the children to help him study, he is taken immediately back into the fold, again becoming one with the others.

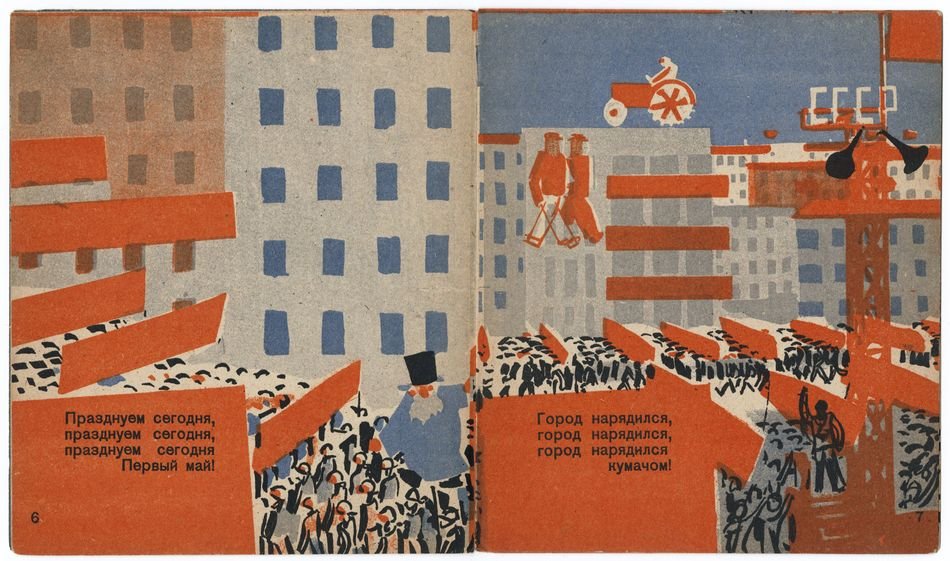

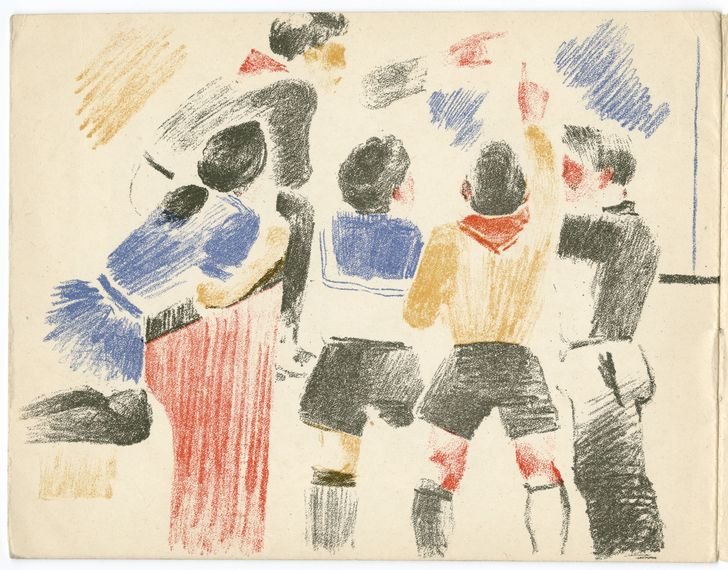

The form of Soviet children’s books also served to exhibit and exalt the collective ideal. Those with text are all in simple, short verses, which lend themselves to group recitation in hypnotic rhythm, as with a military march or work song. For example, the bricklayers in Stroika chant, “First set the rafters / Iron goes on after! / Lay the ceiling and the floor / The hammer dances plenty more! / Vzhi-vzhi, sawdust rains! / Tyap-tyap, splinters again!” The artwork is sketched in a style that lends itself to dynamism but not detail; human figures are hardly differentiated, and most lack facial detail. Bold colors slash across the pages with an emphasis on primary tones, particularly red, hints of the Constructivist movement that preceded the Cultural Revolution. This style reaches its apogee in the V. Ivanova’s illustrations to the 1932 edition of Elizaveta Tarakhovskaia’s Bei v baraban! (Bang the Drum!), whose swirling colors, floating secular icons, and ranks upon ranks of marching, chanting, rejoicing citizens draws the reader into the giddy, overwhelming atmosphere of a true Soviet holiday.

by Leah Goldman

Items Discussed in Exhibition:

- Vladimir Maiakovskii. Guliaem. Illus. by A. Brei. Moscow: Detizdat TsK VLKSM, 1938.