Soviet Policy on Nationalities, 1920s-1930s

The Soviet policy on nationalities, or national minorities, was based on Lenin’s belief that alongside the “bad” nationalism of predatory colonialist nations, there existed a “good” nationalism, that of oppressed nation states yearning for freedom. Lenin believed that a comprehensive state-sponsored program of “nation-building” could fulfill the nationalist aspirations of the many non-Russian peoples of the Soviet Union and thus prevent them from aspiring to any real autonomy.

The years of the “great transformation” from 1928 to 1932 saw the Soviet nation-building project peak in intensity, a process historian Yuri Slezkine has described as “the most extravagant celebration of ethnic diversity that any state had ever witnessed."[1] Although all nations were equal in theory, some were considered to be more civilized, while others were decidedly “backward.” Backward nations needed special help to reach the stage of development of their “Great Russian brothers.”

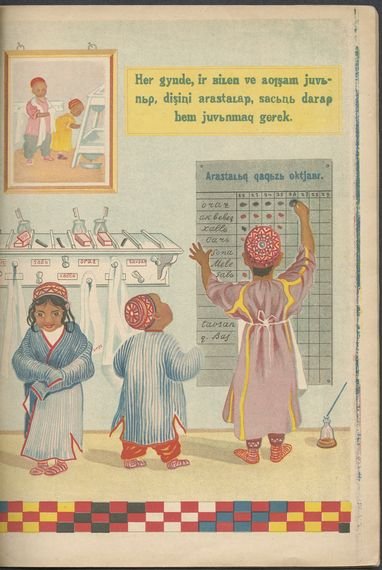

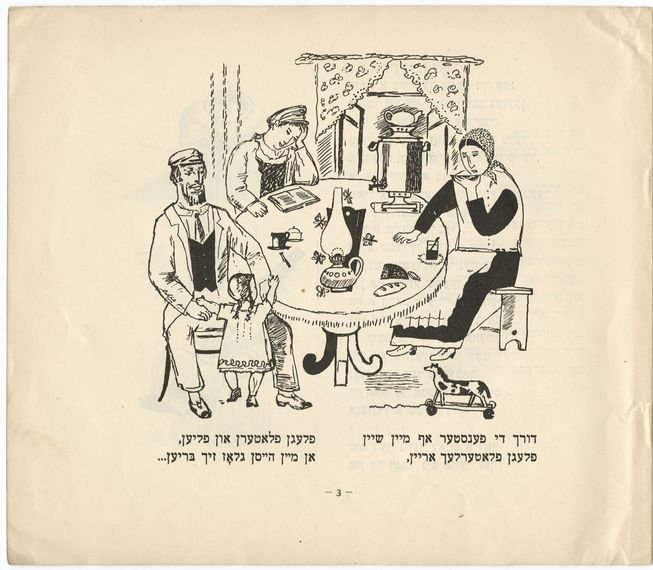

Nation-building consisted of assigning to each officially recognized national minority its own territory (however small), developing a unified and standardized national language whether or not one had previously existed, and rolling out extensive cultural and educational programs in that language. Children’s books in the national languages of the Soviet Union were part of the program [see Noobatchylar (Class Monitors) in Turkmen, and the Yiddish edition of Marshak’s Vchera i segodnia, entitled Nekhtn un haynt (Yesterday and Today)], as it was deemed essential to the success of socialism as an ideology that each child should learn its precepts in his or her own mother tongue. Not just socialists, but happy ones: “Allow [a discontented minority group] to use its native language and the discontent will pass by itself,” asserted Stalin.[2]

The formula “nationalist in form, socialist in content” underscores the understanding that the different languages used within the Soviet Union can all be made to convey the same messages: minority languages, local customs and traditions, ways of life and dress were all matters of form which could be inscribed with socialist meaning.

Noobatchylar, a bilingual book in Turkmen and Russian, portrays the different responsibilities of students in a Turkmen “Experimental and Exemplary Kindergarten.” In a reflection of structures in the adult world, each Soviet kindergarten student is responsible for monitoring the state of the classroom and classmates’ behavior. Some children are responsible for inspecting the personal hygiene of their fellow students, while others feed the class pets, water the class plants, or serve breakfast. At the end of the day, all the class monitors report on the performance of their peers. Although all the children wear traditional Turkmen garb, they are united with other Soviet children by their commitment to order and cleanliness, and their devotion to Lenin, whose childhood portrait is displayed in their dining room.

An important corollary of the nation-building project in children’s literature is the sudden flowering of books aimed at Russian-speaking children designed to introduce and celebrate the varied tapestry of peoples, with their distinctive lifestyles and customs, living within the borders of the USSR.

Evreiskii kolkhoz (Jewish Collective Farm), for example, shows a new collective farm peopled by former Jewish craftsmen who have abandoned their obsolete lifestyles for a new beginning on the land. The book was written to debunk the stereotype that Jews are incapable of farming. On the Ne unyvai! (Don't Lose Heart!) collective farm, Jews even turn their hands to pig breeding.

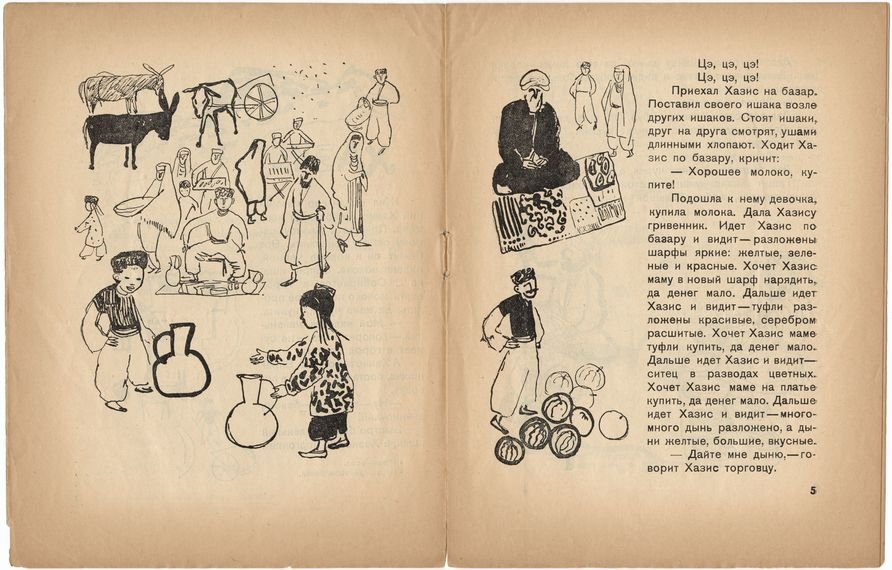

The fresh line drawings in Khazis give the impression of having been sketched from life. The illustrator, Tat'iana Alekseevna Mavrina (1900-1996), was well-known as a graphic artist as well as a prolific painter of nudes and still life. Mavrina and her husband Nikolai Vasil’evich Kuz’min were members of “Group 13,” an association of graphic artists created in 1929. In 1976 she became the only Soviet artist ever to receive the Hans Christian Andersen Award for children’s literature illustration.

In the 1920s and 1930s, many children’s books were written to introduce children to the far-flung corners of the USSR, which are so different from the Russian heartlands. Several books in the University of Chicago's collection are set in the Central Asian lands, which had only been added to the Russian Empire in the final half-century before the Revolution. The ancient city of Bukhara was annexed as recently as 1920, when the Emir was driven out by the Red Army, making it a particularly exotic setting for children’s stories, where daily life was as different as could be from that in Moscow and St. Petersberg. The platform of children’s books provided an opportunity to expose young readers to different landscapes and lifestyles, while underscoring the political message that socialism is a universal doctrine applicable to all.

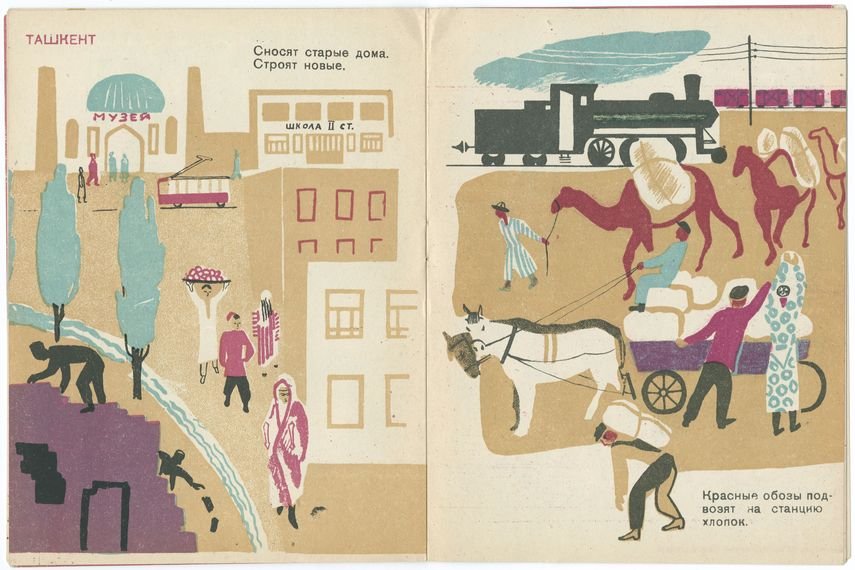

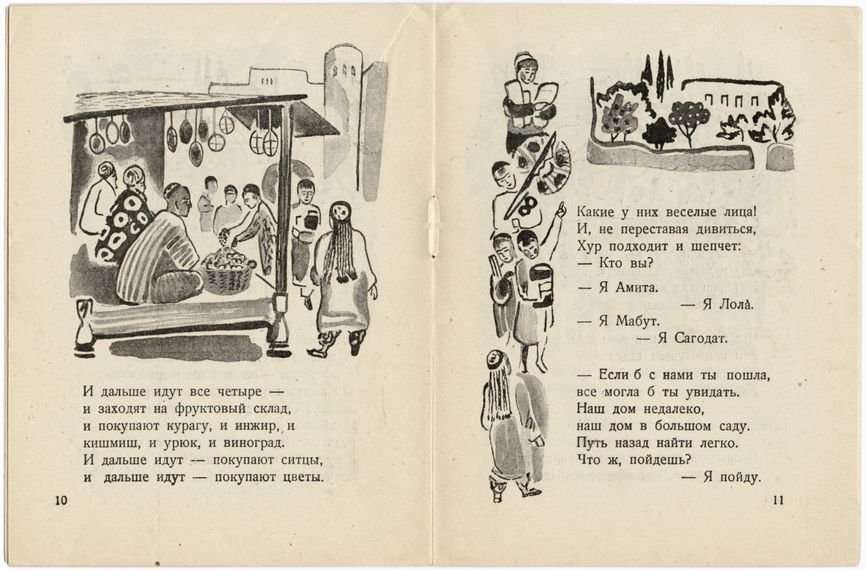

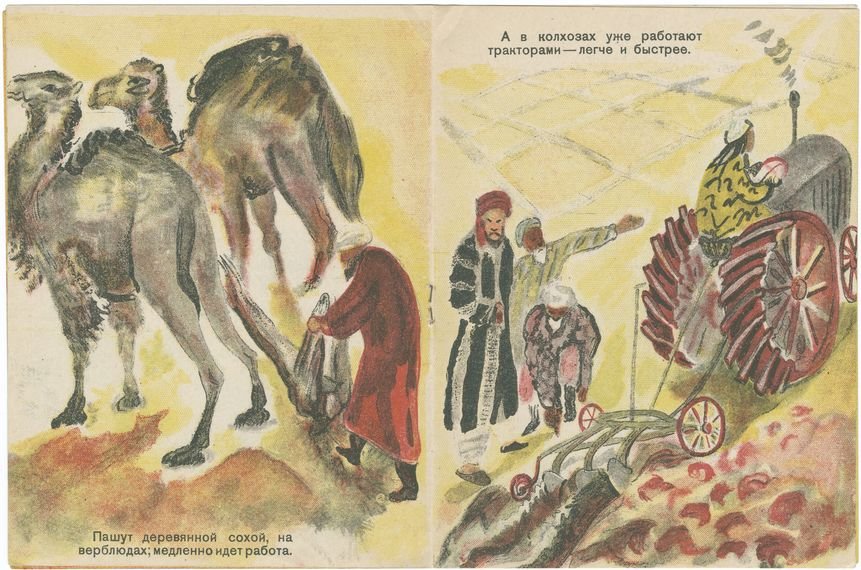

These children’s books about Central Asia share themes in common with books about other distant regions of the USSR. They provided children with ethnographic detail both in the text and the illustrations to acquaint Russian children with byt (everyday life) of their distant fellow citizens. There is also a subgroup of books that moves beyond the depiction of exotic daily lives to introduce the theme of the rapid transformation of these lives under the Soviet system. In books such as A. Petrova’s Ot Moskvy do Bukhary (From Moscow to Bukhara) and Khuriat iz Bukhary an explicit contrast is set up between the old way of life and the new. The old way of life is coded negatively, associated with poverty, hardship, superstition, and inequality between classes and sexes, In the new Soviet life, science and technology make work light, and comradeship rules the day.

From Moscow to Bukhara juxtaposes the old way of life in Bukhara with the new lifestyle that is rapidly spreading through the land, even far from the centers of political and economic power. Trains replace camels, canals are dug by heavy machinery, and tractors speed up the cotton harvest. In the illustration shown, the mosque has been re-labelled “Museum,” a tram has appeared, and new buildings, including a secondary school, have sprung up to replace the old.

In this story, Khuriat is a girl with a traditional upbringing in Bukhara. She spends her days doing household chores and waiting on her father hand and foot. One day she meets a group of happy, independent children who live in a Soviet children’s home, and they invite her to live with them. She joyously accepts the offer and embarks on a brave new life, with toy planes and trains to play with, and plenty of pencils and paper to learn with.

by Flora Roberts

[1] Yuri Slezkine, “The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism,” in Sheila Fitzpatrick, ed., Stalinsim: New Directions (London, New York: Routledge, 2000) p.313.

[2] J. Stalin, Marksizm i natsional’no-kolonial’nyi vopros: Sbornik izbrannykh statei i rechei (Moscow: Partizdat TsK VKP(b), 1935) p.43.