Patronage and Power

Ada Palmer and Eufemia Baldessarre

As classical culture became a tool of competition for the powerful, humanists and artists came to be expected ornaments of kingly courts, republican capitals, Church centers, and of any merchant household aspiring to political status. Florence’s celebrated Medici family began as wealthy bankers, but spent lavishly on art, scholarship, libraries, and public works, using the nobility of antiquity to win the respect and awe of peers and foreign powers. While relationships with patrons like the Medici were sometimes intimate and familial, serving a patron remained a form of unfreedom whose tensions shaped all Renaissance art and literature.

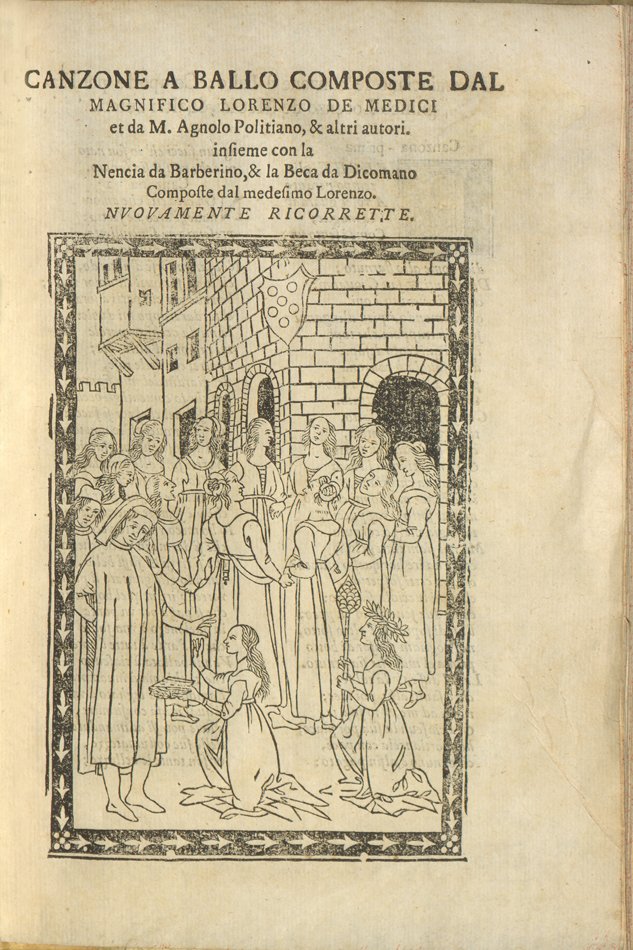

Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494)

Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449-1492)

[Milan: B. Gamba, 1812]

Rare Books Collection

The Beca da Dicomano is a satirical poem written by the Florentine poet and diplomat Luigi Pulci, during his early years serving the Medici family. The poem was inspired by and parodies Lorenzo de’ Medici’s own poem Nencia da Barberino. In this edition both works are mistakenly attributed to Lorenzo. Written in Florentine dialect, the poems contain explicit language and sexual allusions. This contest between patron and client to produce the best satirical poem shows how men so unequal in power could compete as equals within the literary world of humanism.

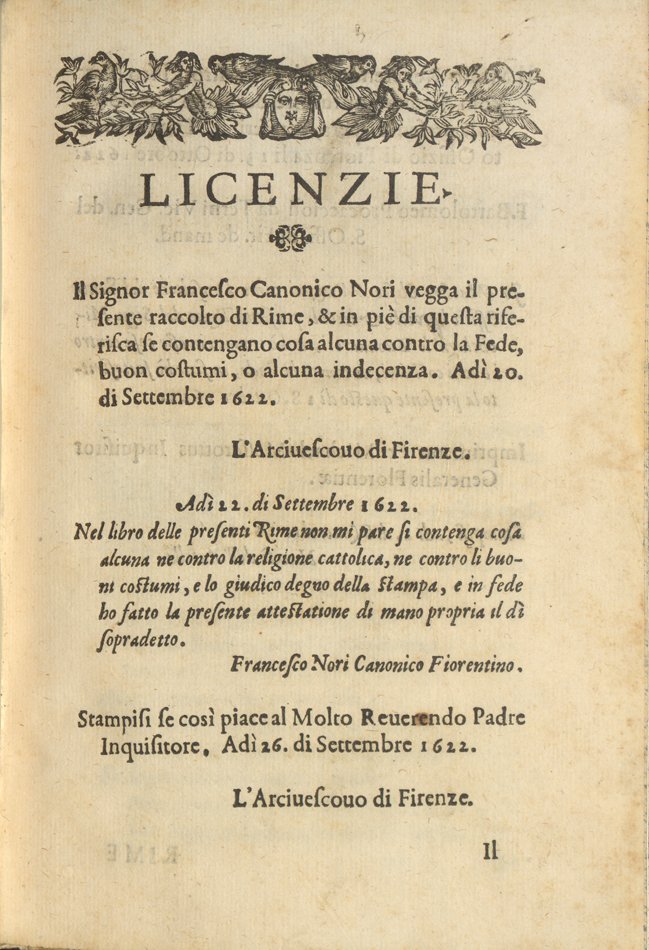

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564)

Rime di Michelangelo Buonarotti

In Firenze: Appresso i Givnti, 1623

Rare Books Collection

Rome and Florence battled over Michelangelo, who wrote of his frustrations as a living tool in the cities’ cultural competition. As a youth he had lived in the household of Lorenzo de Medici, among poets and humanists. When the Medici weakened, Rome offered wealth and fame, but Michelangelo describes how imperious and demanding patrons like Pope Julius II made even great commissions like the Sistine Chapel ceiling feel more like a yoke than a blessing. This first edition of Michelangelo’s poems was censored by his great-nephew, who purged all criticisms of the Church, and all homoerotic references to Michelangelo’s lover Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. While earthly love was censored, images of sacred or Platonic love remained—ideas shaped by the humanist scholars Michelangelo had known in the Medici household. Michelangelo died in Rome while working on St. Peter’s, but asked to be buried in Florence so he could see its cathedral one last time on Judgment Day.

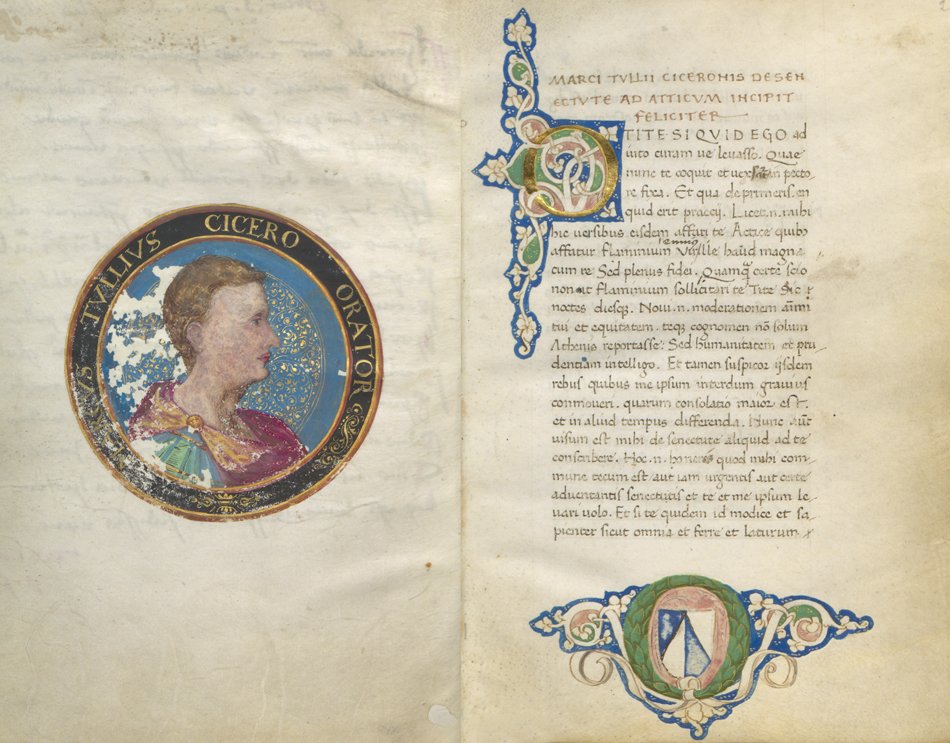

Cicero

Ca. 1400

Codex Manuscript Collection, Gift of Prof. Theodore Silverstein

This fanciful portrait of young Cicero introduces his dialogs On Old Age, On Friendship, and Stoic Paradoxes. The white vine illumination, vines formed by negative space within a blue border, originated in northern Italy, and became a signature of lavish editions of Greek and Latin classics since so many descended from Florentine originals. The volume also contains a poem praising Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, a relic of how much scholars depended on princely patronage in the age when a book cost as much as a house.

Luigi Pulci (1432-1484)

In Firenze: Con licenza de’ Superiori, 1732

Rare Books Collection, Gift of Olga Menn and Paul Menn

The Morgante strongly shaped the Italian tradition of Italian vernacular epic poems. Luigi Pulci was commissioned to write it by Lorenzo The Magnificent’s mother, Lucrezia Tornabuoni, to celebrate a new alliance between France and Italy (primarily Florence) centered on the two regions’ shared Christian piety. While Pulci’s patroness expected a dignified and solemn poem, Pulci instead produced a parody of the epic genre, with more pagan and transgressive themes than sacred ones, demonstrating the tensions that could arise between patrons and their clients.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527)

Vinegia: Per Nicolo d’Aristotele detto Zoppino, 1531

Rare Books Collection, Gift of Elsie O. and Philip D. Sang

Machiavelli survived many Florentine tumults: the death of Lorenzo de Medici, the French Invasion, the expulsion of the Medici, and the rise and fall of Savonarola. He worked tirelessly for the republican government that ruled Florence after Savonarola’s execution, but was banished after the Medici recaptured the city. Machiavelli wrote this satirical comedy The Mandrake during his exile, and packed it with criticisms of religion, politics, and society, depicting lustful conspirators, a corrupt and greedy friar, and a mother who urges her married daughter to commit adultery. The play’s shocking ending, in which adultery works out well for all involved, starkly reverses the moralizing lessons which usually shaped Renaissance drama.