Rome and Its Ruins

By the sixteenth century, Rome—capital of Christendom and former center of a great Empire—had been overtaken in magnificence by many other cities in Europe. To claim contemporary importance, Rome’s advocates looked to the past—the physical remnants of which were crumbling around them. The reconstructive efforts of Bartolomeo Marliani, Pirro Ligorio, and others (who did not always agree!) were part of the larger project of regaining classical knowledge. They promoted this both for its own sake and to instruct and inspire others, at a time when so much—text, art, and architecture—had been irrevocably lost. Scholars and artists used their own experience, inscriptions, archaeological evidence, and ancient literary descriptions—along with a fair amount of imagination—to portray the city as both reconstructed and ruined. The tensions between ambitious scholarly projects and the limited resources available were always present, as were tensions between antiquarians with different ideas about the past.

Engraving with etching

Antonio Lafreri, publisher

1546

From the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae

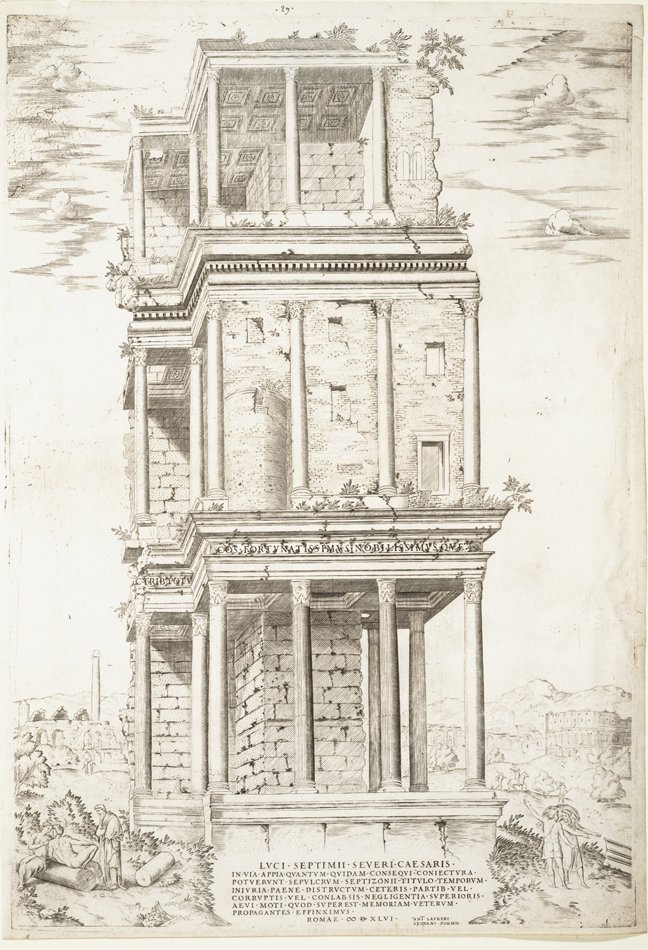

Some monuments were too fragmentary to be accurately reconstructed. The Septizodium mystified early modern antiquarians because only a small portion of what had clearly been a much larger structure remained. One of many ancient buildings to be cannibalized for building materials in this period, it was dismantled in 1585 by Sixtus V to provide stone for the construction of the base of the obelisk in St. Peter’s square. Prints like this are our best evidence for its former appearance.

Etching with engraving

Jan and Lucas van Doetecum, etchers

Hieronymus Cock, publisher

[1551-1561?]

From the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae

Lovers of antiquity were faced not only by the chasm of time elapsed, but also by the rude fate of the remains of ancient Rome. Sculptures unearthed were collected by wealthy families, but often remained haphazardly displayed in gardens like this.

Bartolomeo Marliani (d. 1560)

In Roma: Per Antonio Blado, 1548

Rare Books Collection, Berlin Collection

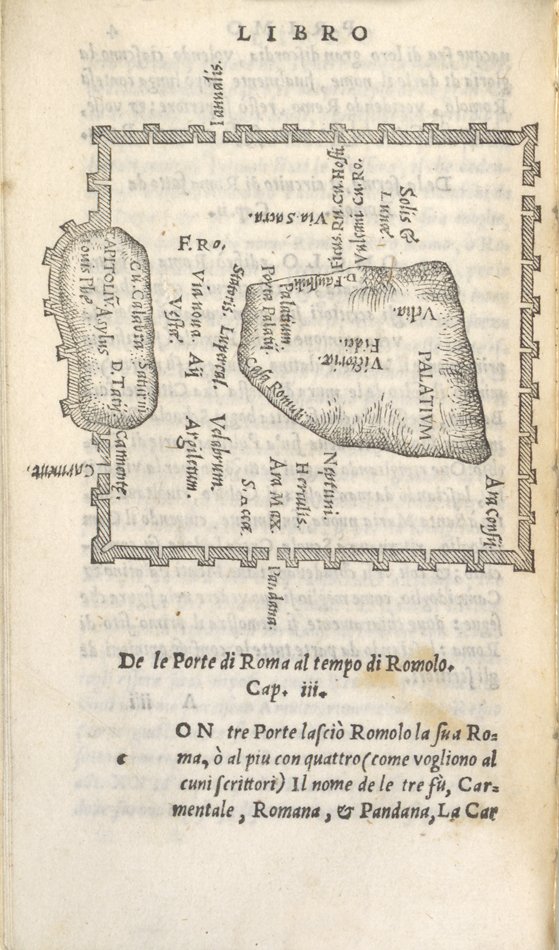

This book is an Italian translation of Bartolomeo Marliani’s Topographia Urbis Romae. It was not unusual for Marliani and other antiquarians to get things wrong, in part or in whole. This map of the pomerium, the sacred boundary of the city that was mythically traced by Romulus and defined the heart of the ancient city, reflects the common compulsion of antiquarians to “fix” irregularities they encountered. Here the pomerium is depicted as a nearly perfect square, only allowing a slight deviation from this ideal geometry to accommodate the Capitoline Hill.

Bartolomeo Marliani (d. 1560)

Venetiis: Apud Hieronymum Francinum, 1588

Rare Books Collection, Berlin Collection

Nota bene: The building pictured here is erroneously identified as the Temple of Peace. It is in fact the Basilica of Maxentius.

Bartolomeo Marliani (d. 1560)

Basileae: Per Ioannis Oporinum, 1550

Rare Books Collection, Berlin Collection

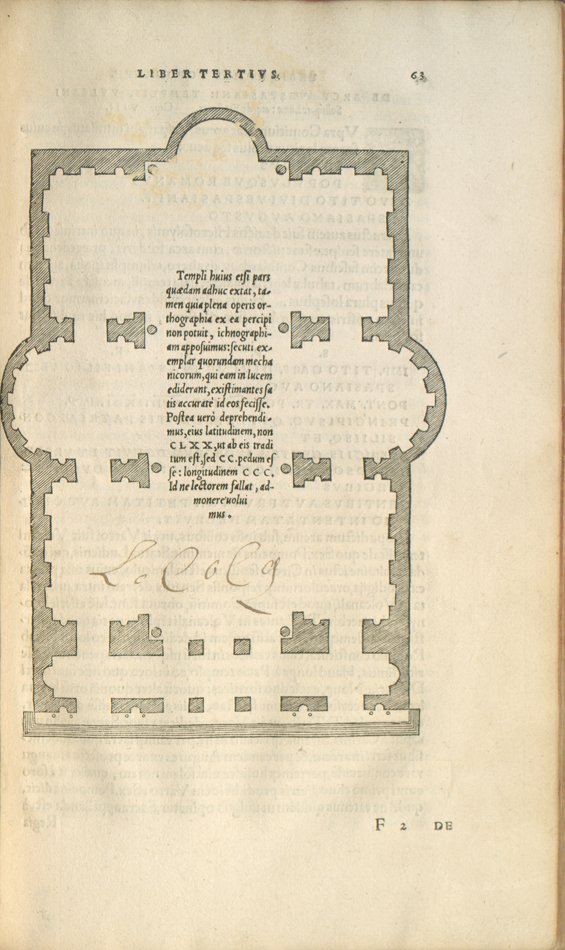

Medieval guides to Rome often included a range of sites that were classical, religious, and secular. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, burgeoning antiquarian studies led to the first guides focused entirely on the monuments of ancient Rome. Bartolomeo Marliani published an early topographical guide of ancient sites. This book, originally published unillustrated in 1534, provides a region-by-region account of known buildings (and a few works of art) of ancient Rome. In 1544, Marliani added illustrations, including modern views of ruins, reconstructions, and architectural plans. On display here is a detailed plan of the Circus Maximus.

Etching and engraving

Cavalieri, Giovanni Battista de’ Dosio, Giovanni Antonio, engraver

[1569]

From the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae

Engraving with etching

Antonio Lafreri, publisher

1547

From the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae

to see Rome restored to its zenith were confronted on a day-to-day basis by scenes like the dilapidated Arch of Titus as they traversed the city.

Pirro Ligorio (ca.1513-1583)

In Venetia: Per Michele Tramezino, 1553

Rare Books Collection

Early modern scholars largely relied on ancient texts to reconstruct the topography of ancient Rome. Pirro Ligorio is notable for his use of archaeological evidence, such as coins, statues, and inscriptions, together with texts to locate ancient buildings. In this book, he discusses the locations of the circuses, theaters, and amphitheaters. In the appendix, called “Paradosse,” he “disputes the common opinions on various and diverse locations of the city of Rome.” Working against the “grave errors” of other writers (including Marliano with whom he often disagreed), Ligorio claims to be “using [his] ingenuity to prove the truth.”

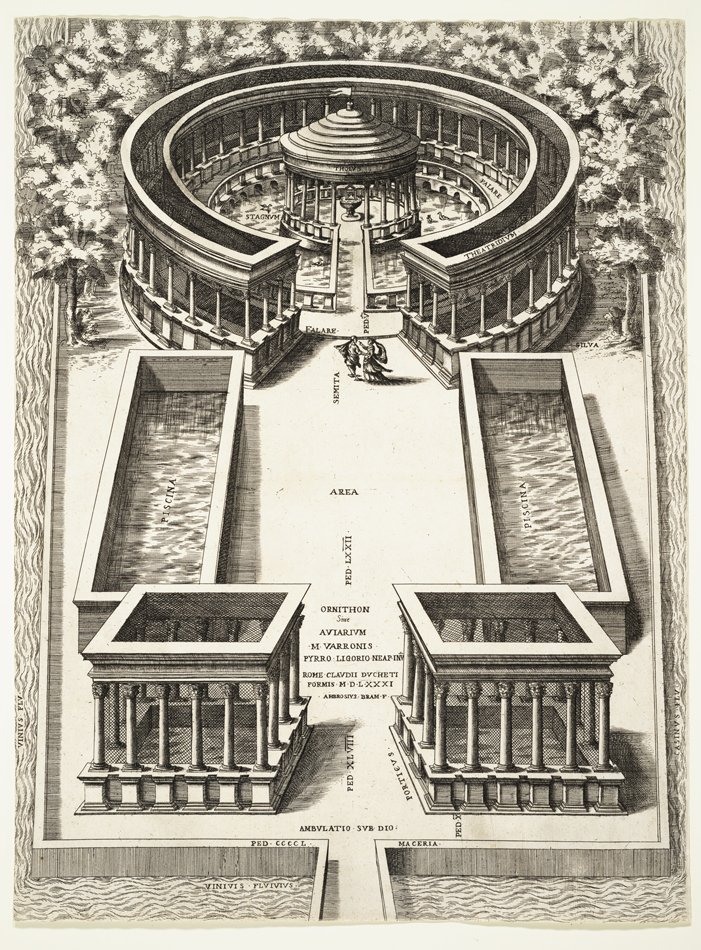

The Aviary Of Marcus Varro

Etching with engraving

Ambrogio Brambilla, Pirro Ligorio, Claudio Duchetti, engravers

1581

From the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae

In addition to his writings, Pirro Ligorio (1512-1583) produced architectural drawings and reconstructions of ancient Roman buildings. This image of an ancient aviary is based solely on a description in the De Re Rustica of Marcus Terentius Varro. It has been noted in modern scholarship that its form is similar to that of the so-called Maritime Theater at Hadrian’s Villa outside of Rome, where Ligorio was actively involved in excavation. Ligorio often combined material from multiple sources in his reconshtructions to make up for “gaps”—and for this “creativity” earned a reputation as a forger. It is clear from examples like these that Ligorio often relied on his idea of what antiquities should be to inform his reconstructions.