Mexico City Between Two Antiquities

Stuart McManus

Mexico City, known to many contemporaries as the “Rome and Athens of the New World,” was a vibrant urban space that remained the most populated city in the Americas throughout the early modern period. Yet, there were tensions, since Mexico City was the heir to two different antiquities and traditions, one Mesoamerican and the other Mediterranean, which in some cases overlapped and interacted, and in others came into direct conflict. Early modern Mexico City was born out of a series of destructive wars waged by European forces and their native allies. Missionaries sought to wipe out pre-Columbian religious practices. Indigenous groups, frequently writing in Nahuatl, challenged European settlers in royal courts. Corporate religious organizations, both European and indigenous, fought with each other for privileges both along and across caste lines. European cultural and educational projects thrived: classicizing edifices were built, scholars were trained in the humanist tradition and orations were delivered in Ciceronian Latin. In Mexico City, indigenous and American-born Spanish scholars learned to wield Latin and other originally European intellectual tools, repurposing them to voice their own agendas, and to celebrate and reframe their local antiquity in parallel to the Greco-Roman antiquity. These New World scholars participated in the numerous scientific controversies and legal disputes that waged in Mexico City, and produced a dizzying array of texts and objects that bespeak broader tensions in colonial society.

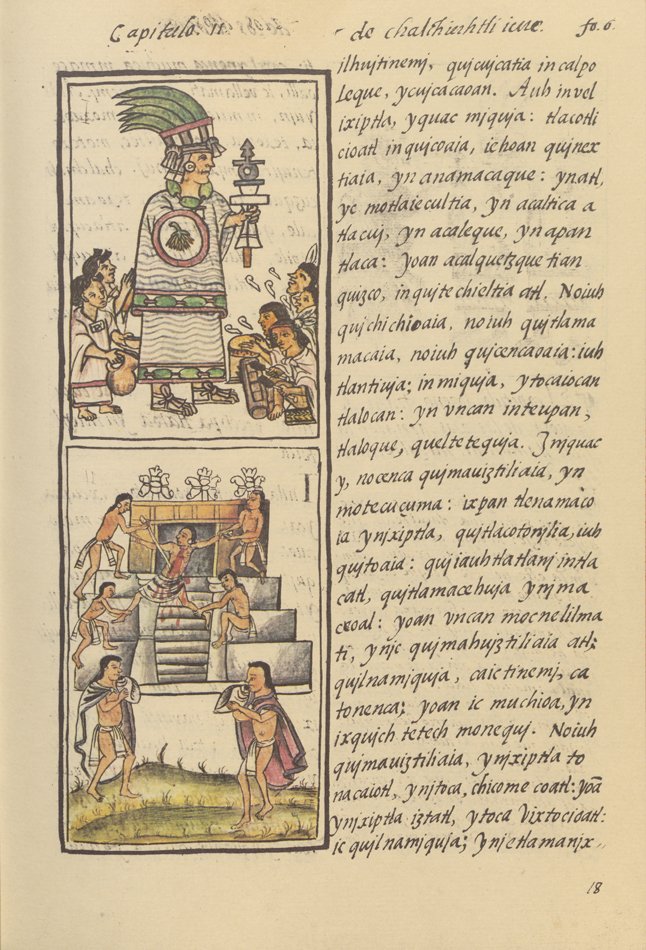

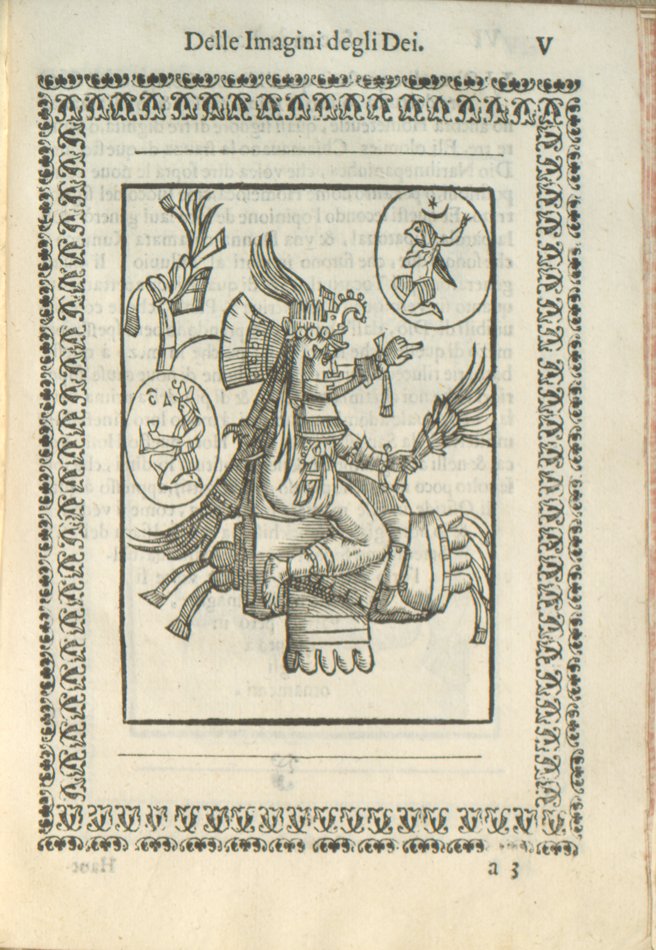

During the early post-conquest period, missionaries, such as Bernardino de Sahagún, carefully documented indigenous religions and customs in order to aid their evangelization efforts. The Codex Florentinus compiled by Sahagún with the help of indigenous collaborators at the College of Santa Cruz de Tlateloco is now one of our most important sources for reconstructing Mexican history. This knowledge not only undergirded missionary projects, but also garnered considerable attention in Europe from readers eager to understand New World culture. These documents served as an important point of comparison for antiquarians, like the renaissance mythographer, Vincenzo Cartari, who included a discussion of Aztec deities is his famous compendium about ancient religions.

Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700)

En Mexico: por los herederos de la Viuda de Bernardo Calderon, 1690

John Crerar Collection of Rare Books in the History of Science and Medicine

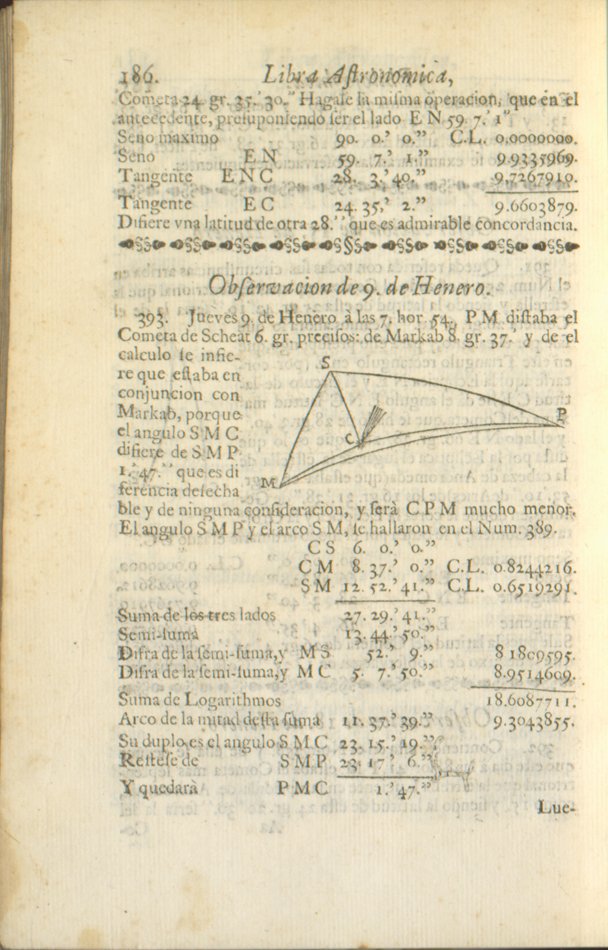

The intellectual world of New Spain was not without controversies. In 1680 a dispute arose between the professor of Mathematics at the Royal and Pontifical University in Mexico City, Carlos de Sigüenza y Gongora, and a German Jesuit, Eusebio Kino over the significance of a comet that appeared in the sky that year. Whereas Kino argued that it was a sign of divine wrath, Sigüenza argued that the comet was a natural phenomenon, not a portent. In making his case, Sigüenza provided considerable astronomical data, which included the first use of decimal notation in the Americas.

Francisco López de Gómara (1511-1564)

In Venetia: Appresso Camillo Franceschini, 1576

Rare Books Collection

The conquest of Mexico-Tenochtitlan by the combined forces of Hernan Cortes and their indigenous allies (most notably the Tlaxcalans) led to the formation of the Viceroyalty of New Spain out of the ruins of the Aztec triple alliance that had dominated Mesoamerica for the previous century. This event was celebrated annually during the colonial period by both indigenous and Spanish inhabitants of the city. Accounts of the event also circulated in Europe.

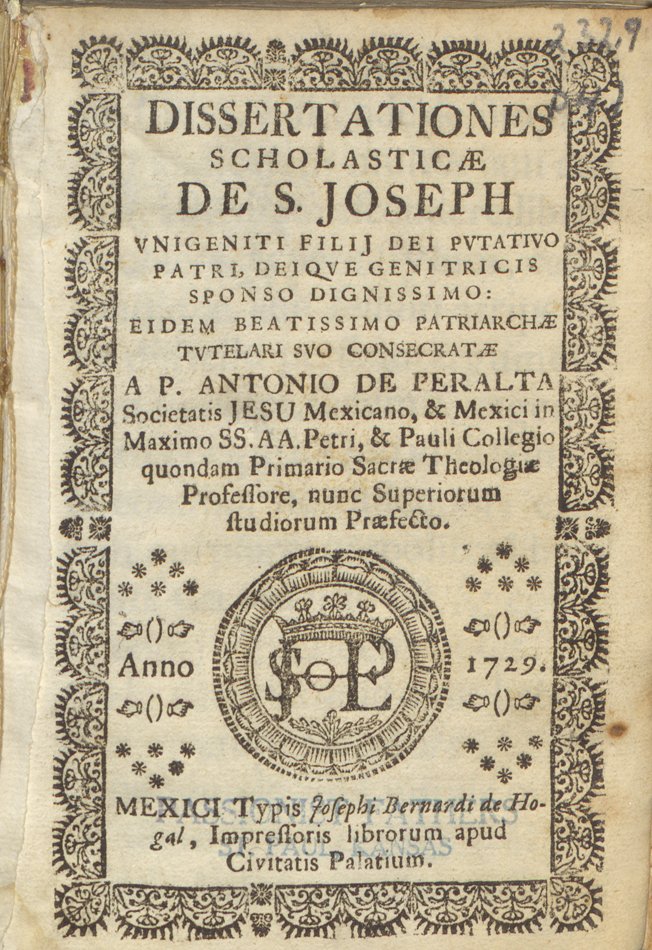

Antonio de Peralta (1668-1736)

Mexici: Typis Josephi Bernardi de Hogal, 1729

Rare Books Collection, Gift of Roland Kulla

In the course of the sixteenth century, universities and colleges on the European model were founded across the Americas. In the institutions, students studied grammar, logic and rhetoric (known as the “arts”) before embarking on the study of more advanced subjects like law and medicine. Latin was the language of instruction and assessment, and students defended theses, which were often printed, in the ancient language.