A City Builds a University

The campaign for a new University of Chicago took place under the cloud of failure that had doomed its predecessor. The first University, or the Old University as it was later to be known, was the product of the denominational loyalty and civic pride of Chicago's Baptists, but it could not develop the financial strength to survive the trials of its early years. Chicago Baptists felt the bankruptcy of their university in 1886 as a bitter blow and resolved to rebuild its prospects at the earliest opportunity.

The founding of the Old University had seemed bright with promise. In 1856, Chicago Baptist leaders accepted an offer from Senator Stephen A. Douglas of "a site for a University in the city of Chicago." Douglas was a leading figure in the city and state, general counsel for the Illinois Central Railroad, and two years away from the critical series of debates with his downstate rival Abraham Lincoln. Though not himself a Baptist, Douglas was willing to give land to any group that would found an institution of higher learning and thus promote the continuing commercial and cultural development of the city.

Ten acres for a campus were set aside on the west side of Cottage Grove Avenue just north of 35th Street, directly across the road from "Oakenwald," Douglas's expansive lakeshore estate. University leaders confidently anticipated financial support from Douglas and his wealthy friends and hoped that he would deed them the remainder of his land as the institution grew.

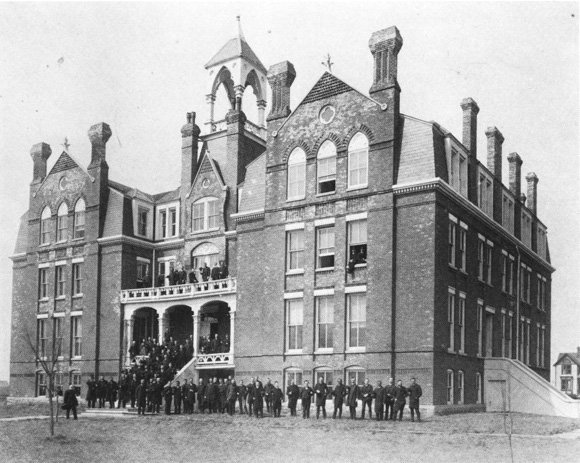

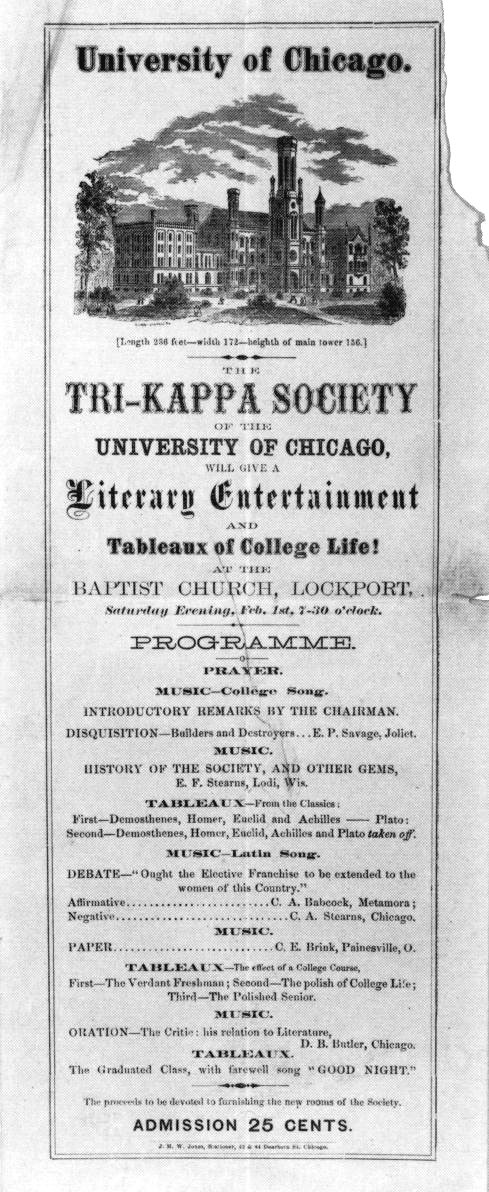

The south wing of the Old University's main building was completed in time for the beginning of classes in 1859. Construction was then begun on the main part of the building, Douglas Hall, and on the Dearborn Observatory constructed on its west side, all of which was completed by 1864. In addition to college courses, a preparatory school was established along with medical and law departments. The newly organized Baptist Union Theological Seminary (BUTS) offered its first classes in Douglas Hall in 1867, and the next year it erected its own building adjacent to the campus. For any outside observer, the two institutions seemed ideally situated to reap the benefits of the increasing prosperity of the Baptist community and the steady southward growth of the city of Chicago.

Those inside knew better. Senator Douglas, who was named the first president of the Old University's board of trustees, died in 1861 without providing the institution a bequest. The financial panics of 1857 and 1873 eroded the prosperity of wealthy supporters, both Baptist and non-Baptist, and the great fire of 1871, while leaving the south side of Chicago unscarred, destroyed the commercial heart of the city. The Civil War also disrupted the lives and fortunes of potential donors, and its impact was felt directly when Camp Douglas, one of the Union's largest prisons for captured Confederates, was located just to the north of the Old University grounds.

Faced with growing debt, the BUTS accepted an offer of land from trustee George C. Walker and moved its faculty, students, and library ten miles south to suburban Morgan Park in 1877. The Old University was not so fortunate. Unable to meet its obligations, primarily the debt incurred in erecting Douglas Hall, the institution lost its mortgage to its principal creditor and was forced to close in the spring of 1886.

Baptist leaders in Chicago and throughout the Middle West were humiliated by the extent of the catastrophe. While the BUTS survived in its suburban refuge, the failure of the Old University left the denomination without an academic base to rival the nearby institutional successes of the Presbyterians at Lake Forest College or the Methodists at Northwestern University in Evanston. Resolving to re-establish a Baptist academic presence in Chicago was a group of determined ministers and laymen including George C. Walker, Henry A. Rust, Frederick A. Smith, the Rev. George W. Northrup, president of the BUTS; E. Nelson Blake, president of the Baptist Theological Union; and the Rev. Thomas W. Goodspeed, financial and recording secretary of the board of the BUTS. They shared, Goodspeed wrote later, an "inextinguishable desire and unalterable purpose" that a new institution should emerge from the old. Goodspeed pressed their case with particular urgency on two laymen with close ties to the situation in Chicago: William Rainey Harper, a professor of Semitic languages at Yale who had just left the faculty of the BUTS, and John D. Rockefeller, the Baptist oil magnate who was serving as vice-president of the BUTS board.

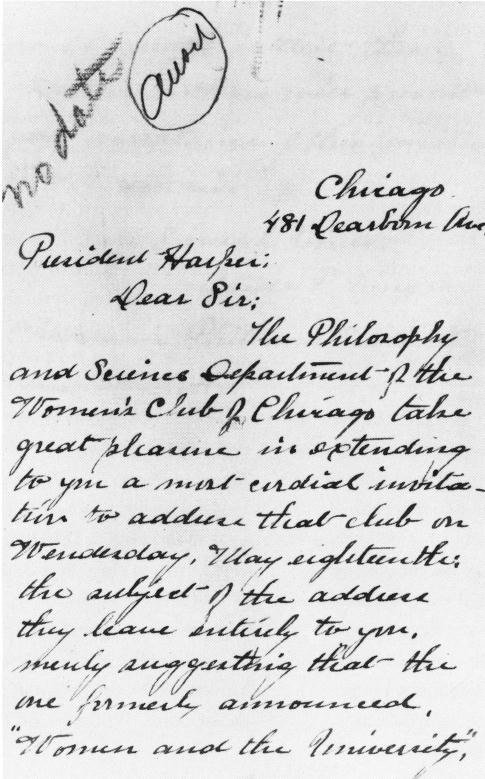

In satisfying the terms of Rockefeller's matching gift within the one-year deadline, the leaders of the new University of Chicago had uncovered a remarkable level of civic support outside denominational bounds. The essential role of the non-Baptist Chicago business community was demonstrated in September 1890, when department store owner Marshall Field, who had given and sold parcels of land on which the University would stand, subscribed his name as one of the institution's six incorporators. The first University Board of Trustees included both Baptists and non-Baptists, among them Charles L. Hutchinson, Martin A. Ryerson, E. Nelson Blake, Ferdinand W. Peck, H. H. Kohlsaat, George C. Walker, Henry A. Rust, Andrew MacLeish, and Eli B. Felsenthal. The non-denominational character of the University received additional emphasis in 1890-91 when newly-elected president William R. Harper began recruiting an internationally trained and largely non-Baptist faculty selected on the basis of scholarly distinction.

A trip by Harper to Europe in the summer of 1891 produced another opportunity for Chicago donors to show their generosity. Learning that the entire stock of an long-established Berlin book dealer was available for sale, Harper submitted a purchase offer of $45,000 and returned to Chicago hoping that donors could be found to underwrite the cost. He was not disappointed. Nine Chicago businessmen including Hutchinson, Ryerson, Kohlsaat, Charles H. McCormick, and Charles R. Crane pledged the necessary amount, and the University immediately acquired one of the largest academic research collections in the country.

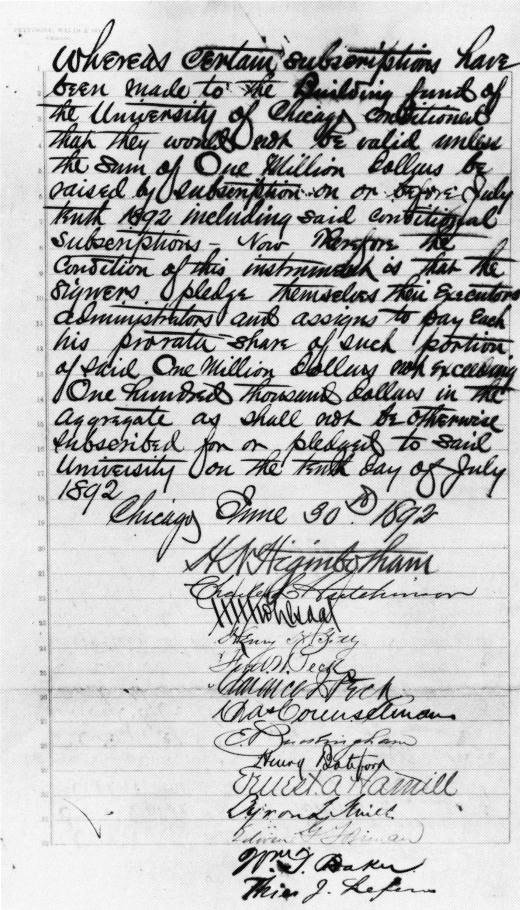

Encouraged by Harper's successes, John D. Rockefeller made a million-dollar gift to the University in late 1890. The next major gift came from Chicago in January 1891, an endowment from the estate of William B. Ogden for a graduate school of scientific research; Ogden had been the mayor of Chicago and for many years the chairman of the Old University board of trustees. Rockefeller provided an additional million dollars for University operations in February 1892, and his generosity prompted Marshall Field to say, "Now Chicago must put a million dollars into the buildings of the University".

Spurred by a $100,000 challenge gift from Field, a frenetic ninety-day campaign was launched. Money for critically needed University buildings was given by Martin Ryerson, George C. Walker, Silas Cobb, and Sidney Kent, and by a new pool of donors representing the women of Chicago: Mrs. Elizabeth Kelly, Mrs. Nancy A. Foster, Mrs. Jerome Beecher, Mrs. A. J. Snell, and members of the Chicago Woman's Club and Fortnightly Club. The campaign was a resounding success, and the University opened in October 1892 with the assurance that through the generosity of Chicago citizens, funds for the classrooms, residence halls, and laboratories essential to its academic work had been secured.