Robert Redfield (1897-1958): Anthropology

Redfield began his anthropological training just as the discipline was completing its transformation from a museum-oriented field to one that sought systematically to study the "patterns and mechanisms of social behavior." As part of a department that was closely linked to sociology, Redfield set out to examine the modernizing process underway in many primitive areas around the world.

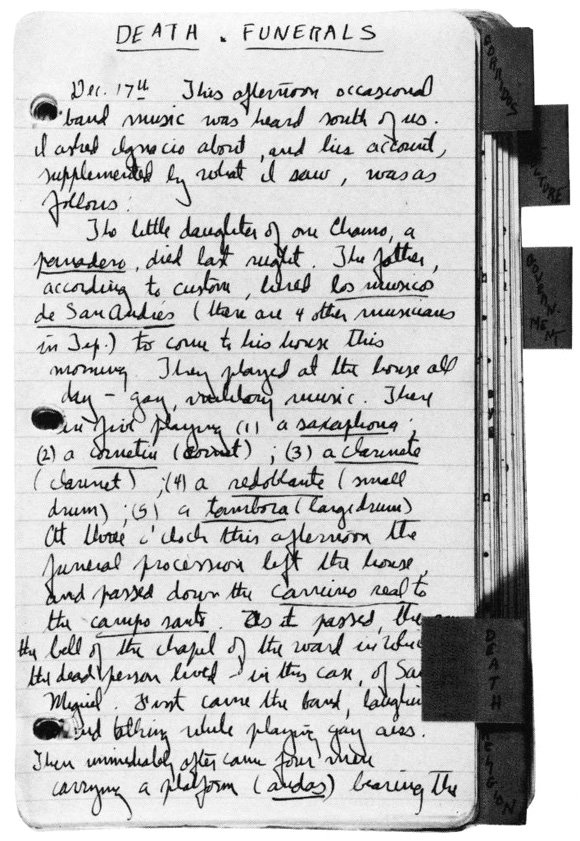

His interest whetted years earlier during a vacation, Redfield traveled to Mexico in 1926 and again in 1930 for what was to be the beginning of a comparative study of four communities at various stages in their confrontation with modern society. Published in 1930, as Tepoztlan: A Mexican Tillage, his dissertation marked the beginning of a series of books on peasant life in Mexico. Chan Kom (1934), the first of three books focused specifically on the Yucatan, was followed by The Folk Culture of the Yucatan (1941). In 1948, Redfield returned to Chan Kom and in 1950 published A Village that Chose Progress.

In addition to his research and teaching duties, Redfield served as Dean of the Social Sciences from 1934 to 1946. A close friend of Robert M. Hutchins, Redfield also organized the Atomic Energy Control Conference in September 1945. The aim was to look ahead to a world living with the consequences of atomic weaponry, and to begin formal discussions of the "techniques of moving toward a world government," one of Hutchins' favorite metaphors.

Redfield's anthropological interests shifted over time, a change reflected in the books he wrote during the 1950s The Primitive World and its Transformation (1953) and Peasant Society and Culture (1956). Leaving the more narrowly defined field of folk and peasant studies, Redfield sought to understand the implications of wider cultural change. Influenced by the work of Milton Singer, Redfield began to synthesize anthropological studies into an historical study of civilization. The program resulting from his work encouraged the inclusion of non-Western civilizations as part of the University's course offerings in the College.

Included among a collection of essays compiled after Redfield's death in 1958 is a version of a lecture Redfield gave shortly after his appointment as Dean of the Social Sciences. The essay, entitled "Anthropology: Unity and Diversity," emphasized the point that anthropology stood astride the breach that separated historical and scientific inquiry. The archaeologist, anthropological linguist, physical anthropologist, social anthropologist and ethnologist were all interested, he said, "in people in general, rather than their own people in particular." In this essay as throughout his career, Redfield emphasized a diversity of anthropological method and the unity that lay in a common way of looking at human culture.