Civil Rights and Women's Organizations

Alongside Mary Church Terrell, Harriet Tubman, and other African American women leaders, Wells formed the National Association of Colored Women in 1896, whose goals included women’s suffrage, desegregation, and equal rights for black Americans. Wells was a founding member of the National Afro-American Council. In 1898, Wells brought baby Herman along on a five-week trip to Washington, where she discussed lynchings with President William McKinley and also lobbied Congress—unsuccessfully— for a national anti-lynching law. Despite Wells’ involvement in many civil rights and women’s suffrage organizations, she did not succeed Frederick Douglass as the acknowledged leader of the African American community after his death in 1895. Modern scholars speculate that the reasons for this include her gender, her “unladylike” conversations about sexuality and murder, and her militancy and fiery temperament.

The new face chosen to lead black America was Booker T. Washington, the head of the Tuskegee Institute. He believed that African-Americans should try to improve their lives through hard work, but also proposed a compromise that made allowances for segregation and disenfranchisement. His views were strongly opposed by Wells and W. E. B. Dubois, and in 1906 she joined Dubois to promote the Niagara Movement, a group which advocated full civil rights for people of color.

Although the Niagara Movement had little impact on legislative action or popular opinion, its goals led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909. Wells attended a special conference leading to formation of the NAACP, following a series of brutal assaults on the black community in Springfield, Illinois in 1908. But, despite her attendance and initial support of this group, Wells was skeptical of its white and elite African American leadership and moderate stance, and after the NAACP voted down Wells’ motion to make lobbying for an anti-lynching law a priority, she severed ties with the organization altogether in 1912. She continued to fight for social justice independently, focusing on women’s suffrage and civic reforms.

Wells continued her involvement in civic activities, carrying on with her anti-lynching crusade, and participating in campaigns against segregation, including the establishment of segregated schools in Chicago. In 1910, she established the Negro Fellowship League to assist poor African American migrants coming to Chicago from the rural South. She also served as the first African American female probation officer in Chicago.

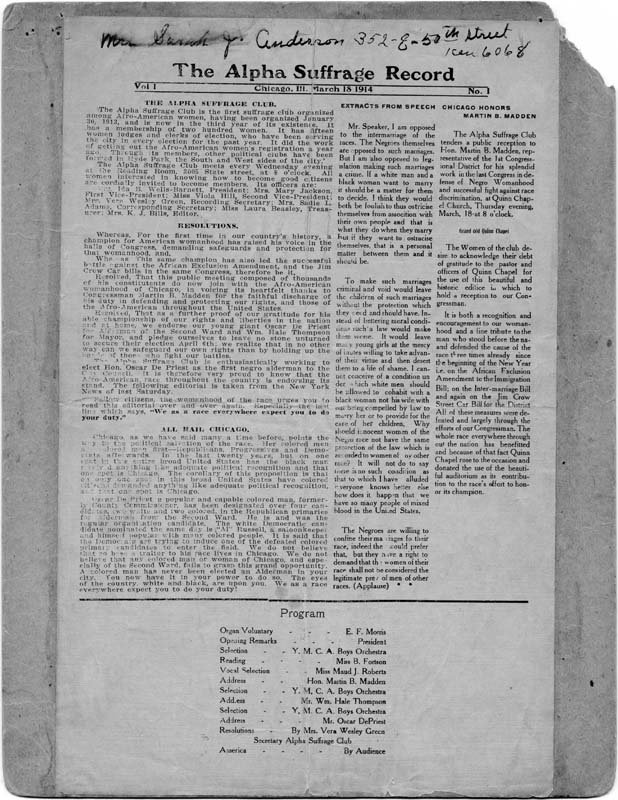

She also took part in marches for women’s suffrage at the national level, even fighting her own battles within these movements. In 1913, Wells joined more than 5,000 women in the Women's Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC. According to a March 8, 1913 article published in The Chicago Defender, “the women of the South…tried to regulate [Ida B. Wells-Barnett] to the “Jim Crow” section of the procession, but she refused and a few of her loyal friends supported her.” She would not be sidelined by white feminist organizations, which often prioritized progress for white women- and the demands of racist leaders over a move to universal suffrage for women. That same year, Wells also founded the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, the first African American women's suffrage organization in the United States.

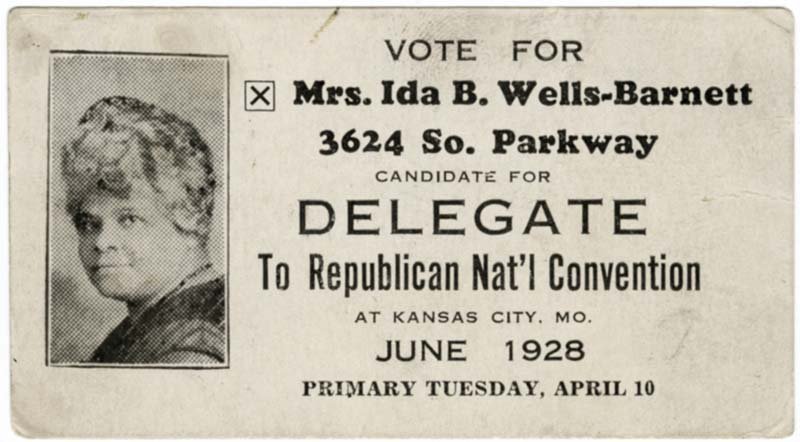

In her later years, she reportedly tired of the politicians who were content with maintaining the status-quo. Wells campaigned as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Kansas City, Missouri, and at age 67, she ran as an independent for the Illinois State Senate, one of the first African American women in the nation to run for public office.

Wells devoted most of her remaining energy to drafting the narrative of her autobiography. In early 1931, after a short illness, Ida B. Wells collapsed and fell into a coma. She died of uremia on March 25th, 1931 and was laid to rest at the Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. Her manuscript for Crusade for Justice was edited after her death by her daughter Alfreda M. Duster and published by the University of Chicago Press in 1970.

Through her writings, speeches and protests, Wells battled against prejudice, regardless of the potential dangers she faced. In the preface of On Lynching: Southern Horrors, A Red Record and A Mob Rule in New Orleans, a compilation of her major works, she writes,

The Afro-American is not a bestial race. If this work can contribute in any way toward proving this, and at the same time arouse the conscience of the American people to a demand for justice to every citizen, and punishment by law for the lawless, I shall feel I have done my race a service. Other considerations are of minor importance.

From the preface of "On Lynching: Southern Horrors, A Red Record and A Mob Rule in New Orleans"