Frances Lowater: International Woman of Astronomy

By Elena Tiedens and Chloe Brettmann

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf6-00016r], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Frances Lowater is seated in the front row, third from the right.

https://photoarchive.lib.uchicago.edu/db.xqy?one=apf6-00016.xml

Introduction:

Frances Lowater first worked at Yerkes as a volunteer research assistant in the summer of 1911. She then worked at the Observatory for a series of summers throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Prior to her first summer at Yerkes, Lowater had earned her bachelor's in mathematical astronomy at the University of London in her native U.K. She then emigrated to the the U.S. and earned her doctorate in physics from Bryn Mawr in 1906. Beginning in 1911, Lowater's time at Yerkes was instrumental in propelling her career as a female British astronomer in the U.S. With the help of a recommendation from Edwin Frost, Lowater earned a job as a professor of astronomy at Wellesley in 1915. As a Wellesley astronomer, Lowater continued to engage with the research of the Yerkes Observatory and volunteered at Yerkes during the summers. She even went with Yerkes astronomers to Green River, Wyoming in June 1918 to watch the eclipse! However, for as much as Yerkes provided Lowater with an inclusive astronomical community, she continually worked as an unpaid laborer alongside the male astronomers of Yerkes.

Science at Yerkes:

Yerkes provided Frances Lowater with a scientific community in which to conduct her astrophysical research work. The Observatory both supplied the equipment needed to complete her experiments and gave her connections to both women and men conducting important astrophysical research. For examples, Lowater's time at Yerkes established her connection with Edwin Frost whom she later collaborated with to publish two articles in The Astrophysical Journal. Yerkes also provided Lowater with the opportunity to partake in scientific expeditions such as a 1918 trip to Green River, Wyoming to observe the full solar eclipse.

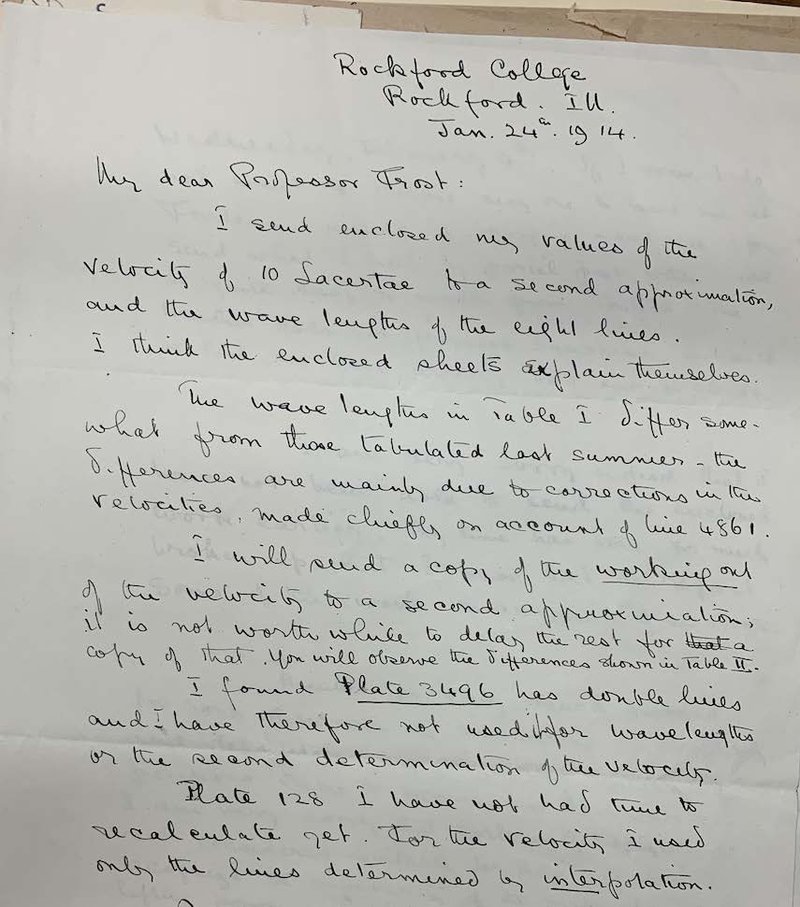

University of Chicago. Yerkes Observatory. Office of the Director. Records, 1891-1946. Box 60, Folder 8.

Frances and Lowater and Edwin Frost correspond about the spectra of 10 Lacertae, January 24, 1914

Transcription of letter from Frances Lowater to Edwin Frost

Rockford College

Rockford, Ill.

Jan. 24th, 1914

My dear Professor Frost:

I send enclosed my values of the velocity of 10 Lacertae to a second approximation, and the wavelengths of the eight lines. I think the enclosed sheets explain themselves.

The wavelengths in Table I differ some from those tabulated last summer -- the differences are mainly due to corrections in the velocities, made chiefly on account of line 4560.

I will send a copy of the working out of the velocity to a second approximation; it is not worthwhile to delay the rest for a copy of that. You will observer the difference shown in Table II.

I found Plate 2496 has double lines and I have therefore not used it for wavelengths or the second determination of the velocity.

Plate 128 I have not yet had time to recalculate yet. Forthe velocity I used only the lines determined to be interpolation.

Explanation:

Lowater's first letters to Yerkes director Edwin Frost spoke to her work ont he spectra of sulfur dioxide, a subject she had researched while a graduate student at Bryn Mawr. Her PhD dissertation, "On the Spectra of Sulfur Dioxide" was published in The Astrophysical Journal in 1906. (1) In 1910, Lowater turned to Frost to help expand her work on the spectra of sulfur dioxide. With Frost's assistance, she published, "The Absorption Spectrum of Sulfur Dioxide" in The Astrophysical Journal in 1910. (2) Building upon her already successful career in astrophysical research, Lowater used her summers at Yerkes to further her research. With Frost, Lowater published "Stellar Wave-Length of lamba 4686 and Other Lines in the Spectrum of 10 Lacertae," "Spectrographic Observation of T Cephei," "Spectrographic Observations of Mira Ceti," and more. (3) The letter refers to Lowater's work with Frost on the 10 Lacertae project. Its tone of mutual respect and understanding speaks to the nature of Lowater's and Frost's collaboration on multiple astrophysical projects. Lowater was not a mere research assistant to Yerkes director but led the charge in astrophysical discovery. Yerkes served as a space where Lowater could both discuss astrophysical problems with her colleagues and use the quality scientific tools of the Observatory to further her research.

(1) Frances Lowater, "On the Spectra of Sulfur Dioxide," The Astrophysical Journal 23(4): 324-343, 1906.

(2) Frances Lowater, "The Absorption Spectrum of Sulfur Dioxide" The Astrophysical Journal 31: 311-338, 1910.

(3) Edwin Frost and Frances Lowater, Stellar Wave-Length of lamba 4686 and Other Lines in the Spectrum of 10 Lacertae," The Astrophysical Journal 40:268-273, 1914; "Spectrographic Observation of T Cephei," The Astrophysical Journal 58, 1923; "Spectrographic Observations of Mira Ceti," The Astrophysical Journal 58, 1923.

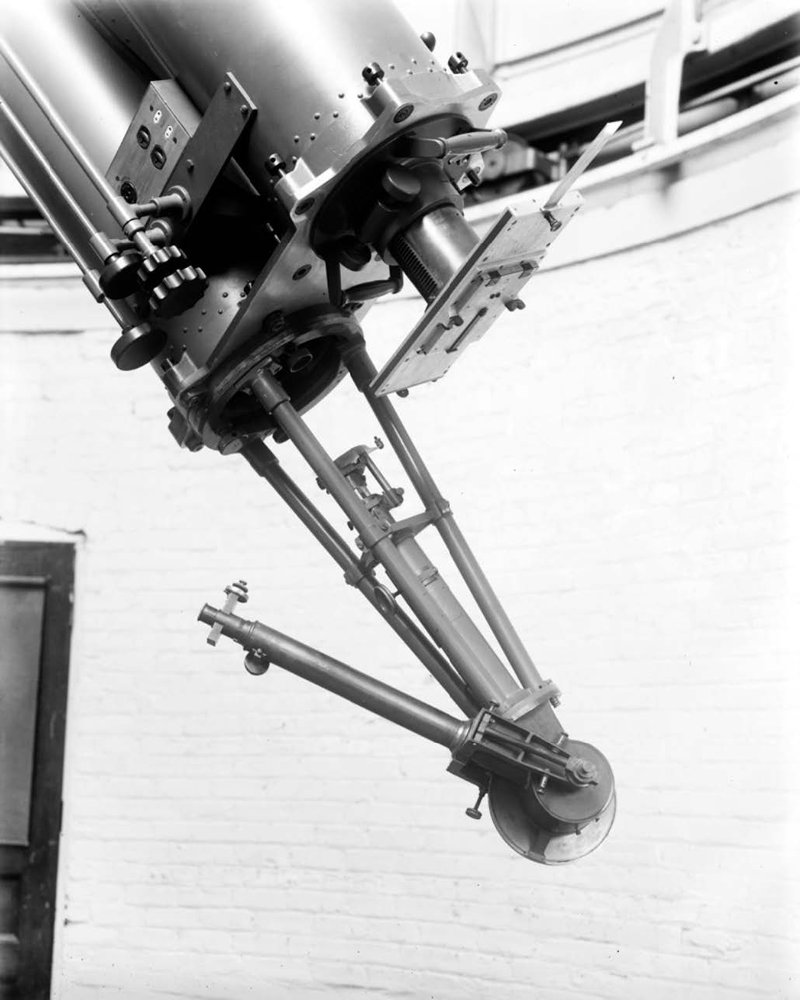

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Yerkes 12-inch refractor telescope with attached spectroscope and plate holder, June 11, 1930

Explanation:

Above is the Yerkes 12-in refractor with an attached spectroscope and plate holder. Many of the astrophysical experiments conducted at Yerkes used spectroscopy to determine the physical and chemical composition of stars. When Lowater conducted her early experiments on sulfur dioxide she would have used a spectroscope like the one attached to this telescope to measure the electromagnetic radiation emitted and absorbed by sulfur dioxide molecules. Later, when Lowater worked on astrophysical research at Yerkes, she likely used this very spectroscope to measure the electromagnetic radiation emitted from stars such as T Cephei and Mira Ceti. The spectroscope was one of many instruments that Yerkes provided to its female (and male) scientists.

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

France Lowater (front row far right) prepares to observe the June 1918 eclipse with Yerkes staff.

Explanation:

Lowater went with a group of Yerkes scientists to observe the June 1918 total solar eclipse from Green River, Wyoming. Teaching her last class of the year on Wellesley on June 1st, Lowater had to leave the east coast later than Frost who left Chicago for Wyoming on May 18th. Nonetheless, Lowater was a ready participant in the observing work conducted during the eclipse. Frost had offered Lowater a job making exposures of objective prisms in Denver during the eclipse, but Lowater instead opted to got to Green River in order to a better view of the eclipse. Here, Lowater rejected a more typical form of women's work - work in astronomical photography - in order to partake in scientific observing. Lowater's sustained involvement with Yerkes allowed her to expand her scientific career into the often male-dominated observing groups of American astronomy. (4)

(4) John Lankford, "Science and Gender: Women in the American Astronomical Community," in American Astronomy: Community, Careers, and Power, 1850-1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 322-326.

Tapping the Yerkes Network

Yerkes also provided Frances Lowater with an astronomical network that propelled her career. Although Lowater may have first come to Yerkes as a little known British female astronomer, her summers at the Observatory helped launch her career as a physics professor at Wellesley College. When Frances Lowater first began her work at Yerkes in 1911, she worked at the physics department at the Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio. However, only five years after Lowater’s first summer at Yerkes, she accepted a far more prestigious position as a professor of physics at Wellesley College – entering a field of science even more restricted to women than astronomy. Notably, Frost provided Lowater with a stellar recommendation for the Wellesley position, writing:

"I regard her as particularly well adapted for the vacancy you refer to, as she has had an excellent training in physics, long experience in the laboratory, and a considerable experience in teaching. At the same time her interests are always strong for research, and she is competent to do it."

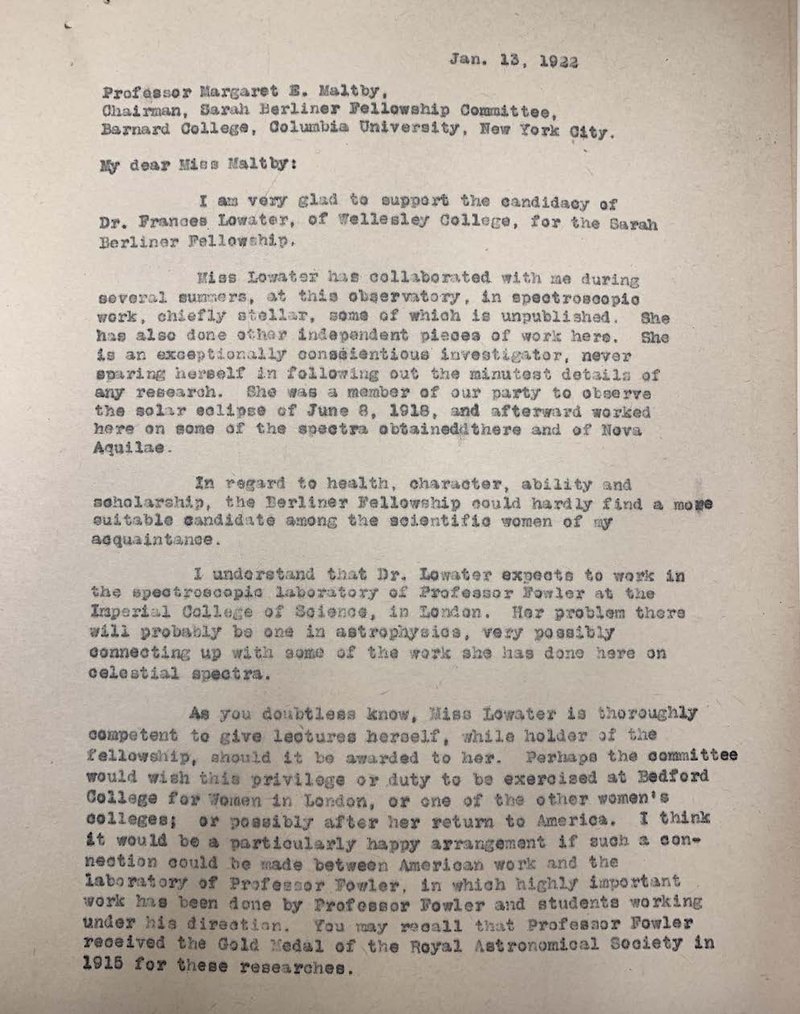

Frost also recommended Lowater for the Sarah Berliner Fellowship – a fully funded fellowship for a woman scientist at any academic institution. (5) Although Lowater was not selected as the 1922 Sarah Berliner Fellow, Frost’s recommendation demonstrates his longstanding dedication to supporting women’s careers.

(5) Margaret Rossiter, Women Scientists in America: Struggles and Strategies to 1940 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1982), 49-50.

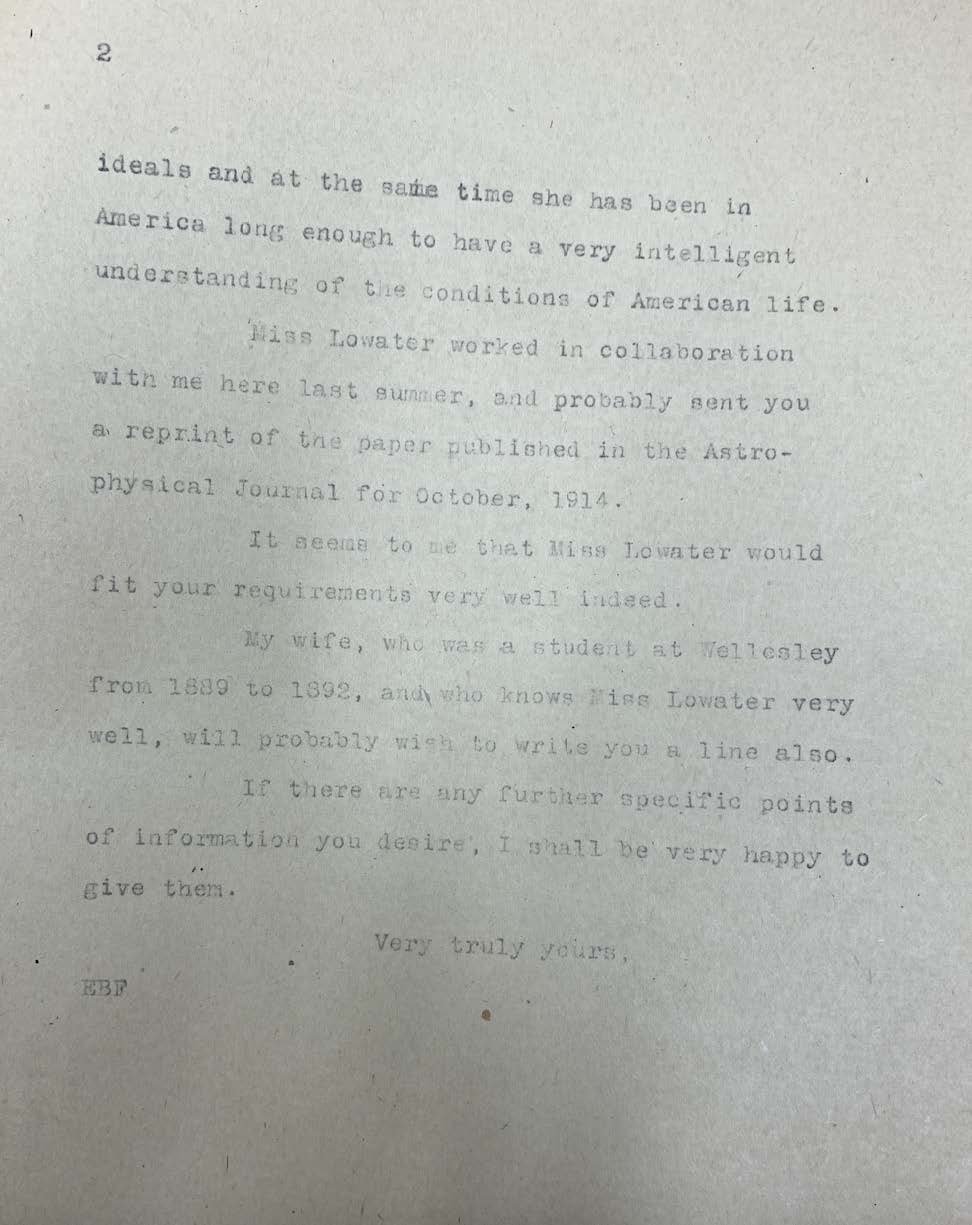

Transcription:

My dear Miss McDowell:

Your letter of March 15th is at hand and I am glad to express to you an opinion regarding Miss

Lowater.

I regard her as particularly well adapted for the vacancy you refer to, as she has had an excellent training in physics, long experience in the laboratory, and a considerable experience in teaching. At the same time her interests are always strong for research, and she is competent to do it. Her line of work has principally been spectroscopic, and she does her work with great thoroughness, accuracy and skill. She is in charge of the physics at Rockford College for the last four years, and has developed her department there to the great advantage of that college.

As you doubtless know, she is an English-woman, but has probably been in this country for at

least ten years. I regard her as a particularly wholesome woman to have in contact with college girls, because she retains many of the best English ideals and at the same time has been in America long enough to have a very intelligent understanding of the conditions of American life.

Miss Lowater worked in collaboration with me here last summer, and probably sent you a reprint

of the paper published in the Astrophysical Journal for October, 1914.

It seems to me that Miss Lowater would fit your requirements very well indeed.

My wife, who was a student at Wellesley from 1889 to 1892, and who knows Miss Lowater very

well, will probably write you a line also.

If there are any further specific points of information you desire, I shall be very happy to give

them.

Very truly yours,

EBF

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Frost recommends Frances Lowater for the Sarah Berliner Fellowship, January 13, 1922.

Transcription:

Jan. 13th, 1922

Professor Margaret E. Maltby,

Chairman, Sarah Berliner Fellowship Committee,

Barnard College, Columbia University, New York City

My dear Miss Maltby:

I am very glad to support the candidacy of Dr. Frances Lowater, of Wellesley College, for the

Sarah Berliner Fellowship.

Miss Lowater has collaborated with me during several summers, at this observatory, in spectroscopic work, chiefly stellar, some of which is unpublished. She has also done other independent pieces of work here. She is an exceptionally conscientious investigator, never sparing herself in following out the minutest details of any research. She was a member of our party to observe the solar eclipse of June 8, 1918, and afterward work on some of the spectra obtained there and of Nova Aquilae.

In regard to health, character, ability, and scholarship, the Berliner Fellowship could hardly find a more equitable candidate among the scientific women of my acquaintance.

I understand that Dr. Lowater expects to work in the spectroscopic laboratory of Professor Fowler at the Imperial College of Science, in London. Her problem there will probably be one in astrophysics, very possibly connecting up with some of the work she has done here on celestial spectra.

As you doubtless know, Miss Lowater is thoroughly competent to give lectures herself, while

holder of the fellowship, should it be awarded to her. Perhaps the committee would wish this privilege or duty to be exercised at Bedford College for Women in London, or one of the other women’s colleges; or possibly after her return to America. I think it would be a particularly happy arrangement if such a connection could be made between American work and the laboratory of Professor Fowler, in which highly important work has been done by Professor Fowler and students working under his direction. You may recall that Professor Fowler received the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1915 for these researches.

Unpaid Labor at Yerkes

While Yerkes certainly provided opportunities by which Lowater could advance her career, her work there was almost exclusively conducted on an unpaid volunteer basis. Although from her first summer working at Yerkes in 1911, Lowater repeatedly asked Frost for work in paid positions, the only time she received compensation from the Observatory was for a couple of weeks of work in September, 1918.

The nature of Lowater’s unpaid labor at Yerkes thus forced her to choose between her work as a scientist and her financial responsibilities. These financial and family care responsibilities were the same obligations that male employers often argued women did not have – giving them recourse for pay discrimination. Although Yerkes was a largely inclusive space for women, this inclusivity was not complete, leaving women like Lowater to negotiate the often competing obligations of their scientific

work and their economic responsibilities.

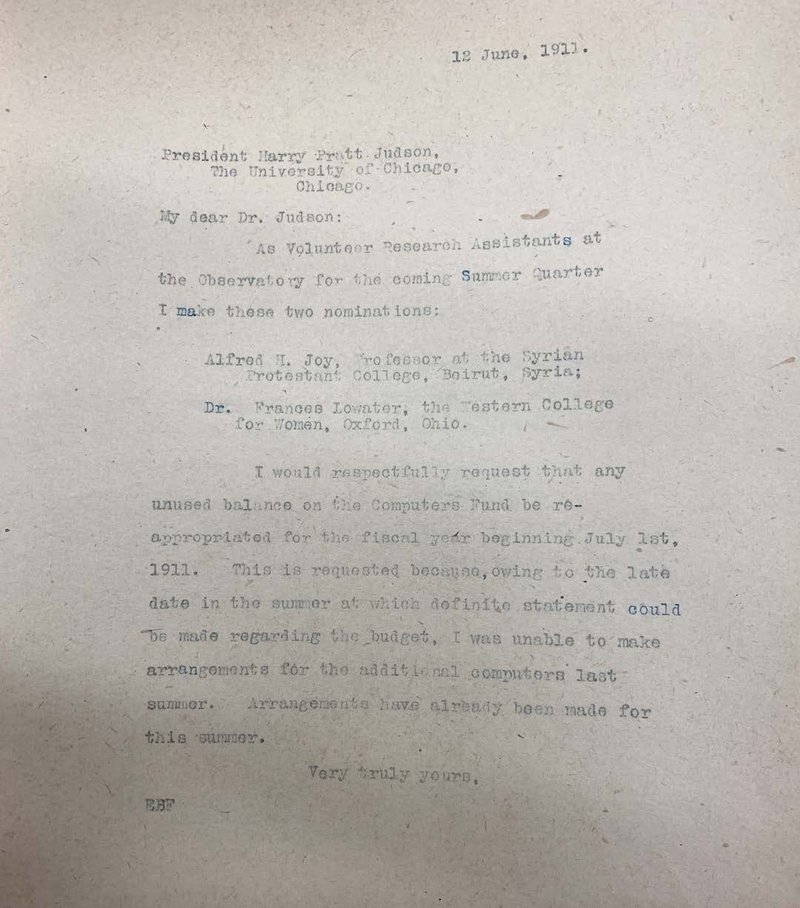

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Edwin Frost appoints Frances Lowater as a summer research assistant, June 12, 1911.

Transcription:

President Harry Pratt Judson

My dear Dr. Judson:

As Volunteer Research Assistant at the Observatory for this coming summer quarter I make these two

nominations:

Alfred H. Joy, Professor at the Syrian Protestant College, Beirut, Syria

Dr. Frances Lowater, the Western College for Women, Oxford, Ohio

I would respectfully request that any unused balance on the Computers Fund be re-appropriated for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 1911. This is requested because owing to the late date in the summer at which definite statement could be made regarding the budget, I was unable to make arrangements for the additional computers last summer. Arrangements have already been made for this summer.

Very truly yours,

EBF

Description:

Although Lowater first volunteered at Yerkes in 1911, throughout the next decade, she advanced in her career, and by 1915, she had become an associate professor at Wellesley. Despite this, she continued to work at Yerkes as a volunteer. For reference, in the same period, Frost took on other research assistants in a volunteer capacity, and not all are women. However, male volunteers came to Yerkes much earlier in their careers. (6) When Lowater came to Yerkes for the first time in 1911, she was five years post-doc and nominated to the volunteer position alongside Alfred H. Joy, a man who worked as a professor without ever having earned a doctorate. (7)

(6) Chloe Brettmann and Elena Tiedens, “A Biographical Approach to Histories of Science and Gender in the Early Twentieth Century: Frances Lowater and Women’s Work at the Yerkes Observatory,” Biennial History of Astronomy Workshop ND- XV, 2023

(7) O.C. Wilson, Alfred Harrison Joy, 1882-1973 (Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 1975).

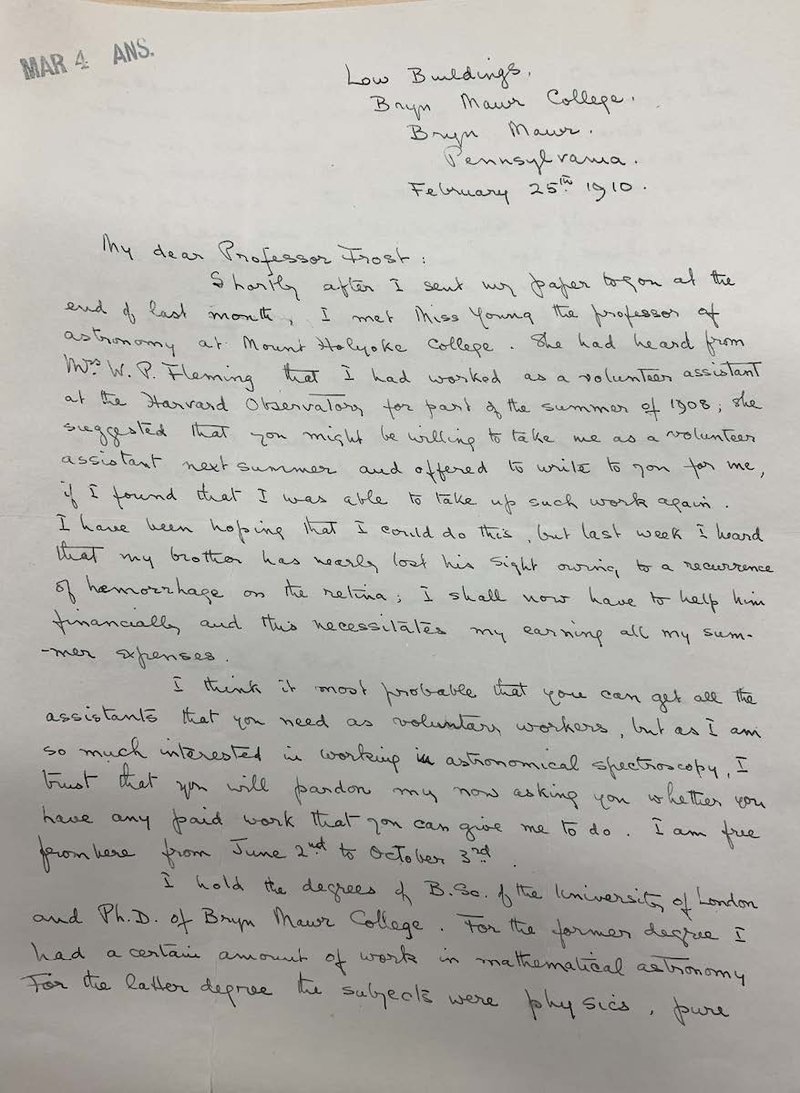

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Letter from Lowater to Frost Feb 25 1910

Transcription:

February 25th 1910

My dear Professor Frost:

Shortly after I sent my paper to you at the end of last month, I met Miss Young, the professor of

astronomy at Mount Holyoke College. She had heard from Mrs. W. P. Fleming that I had worked as a volunteer assistant at the Harvard Observatory for part of the summer of 1908; she suggested that you might be willing to take me as a volunteer assistant next summer and offered to write to you for me, if I found that I was able to take up such work again. I have been hoping that I could do this, but last week I heard that my brother has nearly lost his sight owing to a recurrence of hemorrhage on the retina; I shall now have to help him financially and this necessitates my earning all my summer expenses.

I think it most probable that you can get all the assistants that you need as voluntary workers, but as I am so much interested in working in astronomical spectroscopy, I trust that you will pardon my now asking you whether you have any paid work that you can give me to do. I am free from here from June 2nd to October 3rd.

I hold the degrees of B. Sc. Of the University of London and Ph.D. of Bryn Mawr College. For the former degree I had a certain amount of work in mathematical astronomy, for the latter degree the subjects were physics, pure mathematics and applied mathematics.

Description:

The first time Lowater contacted Frost about a summer position at Yerkes was in 1910. Although she originally intended to accept a position as a volunteer research assistant, Item 7 depicts how Lowater felt she needed a paid position to support her brother after he had fallen ill. Frost, though, did not offer Lowater a paid position for the summer of 1910, and Lowater was forced to put her brother’s medical and care needs ahead of her astrophysical research. Lowater volunteered at Yerkes for the first time the following summer. Although there is no counterpoint for a man in a similar position, Lowater frequently had to confront the choice between her unpaid scientific research at Yerkes, and her economic and family care responsibilities.

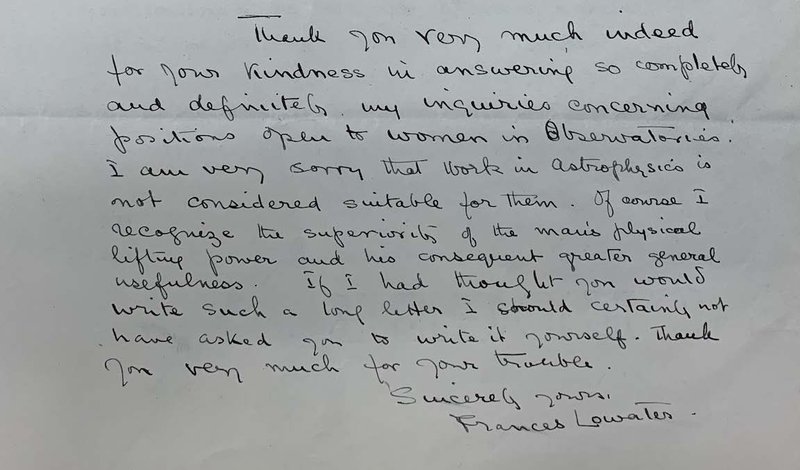

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Frances Lowater in correspondence with Edwin Frost about the work of women in observatories, January 24, 1914.

Transcription:

Thank you very much indeed for your kindness in answering so completely and definitely my inquiries concerning positions open to women in Observatories. I am very sorry that work in astrophysics is not considered suitable for them. Of course I recognize the

superiority of man’s physical lifting power and his consequent greater general usefulness. If I had thought you would write such a long letter I should certainly not have asked you to write it yourself. Thank you very much for your trouble.

Sincerely yours,

Frances Lowater

Description:

Even though Frost largely supported the work of Lowater and the other women of Yerkes, it seems important to acknowledge that his support was not without exceptions. While we do not have access to Frost’s original letter, we can only imagine what it contained given the response it elicited from Lowater. No matter how thoroughly women such as Lowater were integrated into the scientific community of the Yerkes observatory, they still operated from a societal position wholly separate from male scientists. The gender-exclusive social order of the time most certainly conditioned labor at the Yerkes Observatory. These doubts about the capabilities of women in astronomy likely contributed to the unequal pay Lowater received and the unpaid status of the majority of her scientific work at Yerkes.