Yerkes Observatory at the Century of Progress 1933 World's Fair

by Elena Tiedens

Century of Progress Promotional Material. University of Chicago, Special Collections Research Center.

Introduction

In 1933, Chicago hosted the Century of Progress World’s Fair. Like the world’s fairs preceding it, including the 1893 Columbian Exchange also hosted in Chicago, the Century of Progress Fair intended to showcase the accomplishments and cultures of primarily Chicago and the U.S. but also of cities and countries around the world. The theme of the Century of Progress World’s Fair was science and progress, focusing on both “pure” scientific discoveries and industrial applications of science.

Astronomy became an important part of the opening display of the Century of Progress World’s Fair. On May 27, 1933, astronomers at four observatories around the country harnessed the energy of the star Arcturus to light the central building of the fairgrounds. Yerkes director Edwin Frost had suggested the display, and Yerkes served as a contributor to the show, using a photo-electric cell to translate the light from Arcturus to energy used to power the lighting display in Chicago. Yerkes was at first a ready contributor to the Arcturus display but clashed multiple times with fair organizers about issues surrounding scientific versus industrial practices. While Yerkes expected to follow conventions of scientific research in the organization of the exhibit, fair organizers instead hoped for a version of the exhibit that favored entertainment and commercialization.

University of Chicago, Special Collections Research Center

The committee on the Century of Progress 1933 World’s Fair intended to display scientific exhibits of two categories: pure science and applied science. The fair administrators categorized astronomy as a pure science and elicited the help of astronomers such as Yerkes Director Edwin Frost to design the exhibit.

Pure science exhibits were supposed to simultaneously demonstrate a scientific concept and appeal to the public. Frost’s proposal of harnessing the electricity of Arcturus to power the lighting of the fair neatly fit into both goals of the exhibit. His idea was especially appealing to the Century of Progress committee because astronomers estimated that Arcturus was 40 light years away, meaning that the light captured by the Arcturus exhibit left the star in 1893 – the year of the last Chicago World’s Fair. This connection between the two fairs was a powerful tidbit for the Arcturus exhibit’s publicity and advertising.

Planning documents

Partial Transcription:

Division No. I.

This Central Hall of Science at the Chicago Fair is intended to house such exhibits as may be agreed upon from those suggested by the subcommittees on the fundamental sciences and their interrelations. Among others, these sciences are understood for the purpose of this exhibit to be mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, geology, anthropology, psychology, astronomy, and while exhibits should be selected with special reference to the contributions made by the particular exhibit to the advancement of science, it should be obvious that to make them interesting to the average visitor at the fair, some connections between the principle emphasized and a result well known to the public, but not necessarily industrial, must be used in the dramatization.

Thus, in chemistry electrolysis might be chosen as a major contribution, but instead of going only so far as the electrolysis of salt for the production of caustic and chlorine, the exhibit should go so far as bleached pulp or cotton, for example, to show something which the man in the street can recognize at a glance.

. . .

Division No. II.

For the applications of science the individual plans which are being developed by the subcommittees on mechanical engineering, bacteriology, anatomy, medicine, dentistry, geography, steel treating, electrochemistry, entomology, roentgenology, physiology, automotive engineering, agricultural engineering, botany, civil engineering, veterinary science, ceramic engineering, illuminating engineering, electrical engineering, materials testing, chemical engineering, petroleum geology, economic geology, mining and metallurgy, transportation and agriculture, should represent a dramatized method and pattern for all industrial exhibits showing the underlying fundamental features of structure and function that are due to science on which the final industrial machine or product relies or depends, so that in each exhibit the debt to science may be taught. This industrial debt may be brought out through a chronological sequence of developments, through a geometrical or spatial arrangement of stages which indicate it, or where either of these is impracticable, through a verbal statement proclaiming it; these various methods being applicable alike to the functioning of apparatus or machinery and to its form, structure or composition.

As examples of the above, one could visualize as an exhibit for mechanical engineering, a modern printing press with science contributions showing the development of the ink, of the type and type setting, of the machine itself, of the paper used in the machine, of the power which operates the machine, etc.

Contesting the Arcturus Exhibit

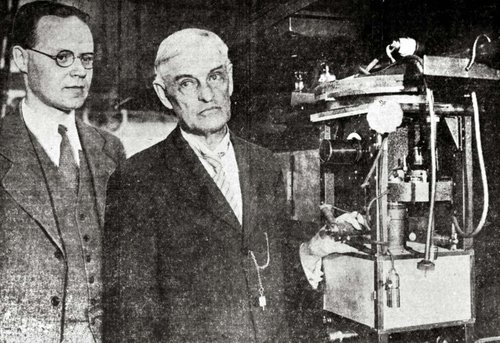

Otto Struve (left) and Edwin Frost (right) stand next to the photo-electric cell used in the Arcturus display. University of Chicago Photographic Archive.

Description:

The Arcturus exhibit operated primarily through photo-electric technology. The light from the star Arcturus entered Yerkes’ 40-inch refractor and then was converted into an electric current through reflecting off of a photo-electric cell. From here, the electric current traveled through amplifying tubes supplied by General Electric and then traveled from Williams Bay to Chicago via Western Union’s telegraph lines. The Century of Progress committee invited three other observatories to participate in the Arcturus ceremony in order to ensure that the production could continue even if it was too cloudy at Yerkes to view Arcturus. Ultimately, Yerkes Observatory, Harvard Observatory, Allegheny Observatory, and the Urbana Observatory sent energy from Arcturus to the fairgrounds in Chicago.

Giving Credit

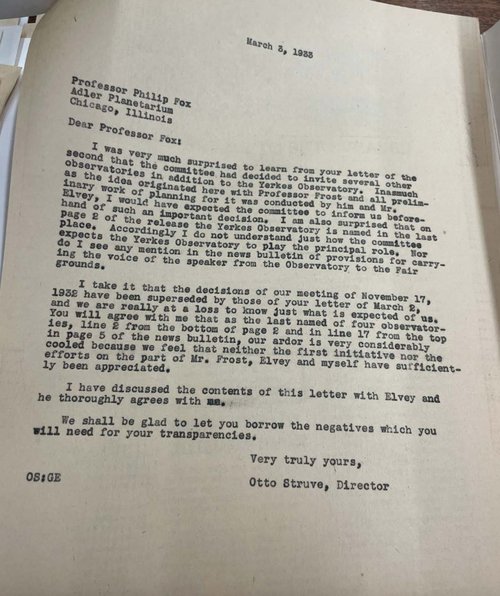

In 1932, Frost had proposed the Arcturus exhibit to the Century of Progress committee. However, by March 1933, the committee had in a large part, taken control over the planning of the ceremony. Committee control alienated Yerkes leadership and demonstrates the differing ways in which scientists and industrialists of the early 20th century went about their work. In March 1933, Yerkes Director Otto Struve wrote to Philip Fox, the director of the Adler Planetarium and a member of the planning committee, that Yerkes faculty and administrators were offended that the committee had invited other observatories to participate in the ceremony without Yerkes’ consent. They also were unhappy that the planning committee had not given Frost and Yerkes enough credit for their role in formulating the ceremony.

This conflict speaks to broader differences between the culture of academic astronomy and the corporate planning of the fair. The academic astronomers saw less value in the successful output of the ceremony on the planned date – acknowledging that cloudy weather had the potential to postpone the ceremony – than the scientific intellect already put into the exhibit. Meanwhile, the fair’s planning committee wanted to ensure the ceremony’s successful end even if that meant departing from the original scientific impetus of the exhibit. “Pure” science then wanted to follow the conventions of placing credit on scientific thinkers, while industrial planners privileged the visible and public success of the stunt.

Otto Struve writes to Philip Fox on the Arcturus Exhibit, March 3, 1933. University of Chicago, Special Collections Research Center.

Transcription

March 3, 1933

Professor Philip Fox

Adler Planetarium

Chicago, Illinois

Dear Professor Fox:

I was very much surprised to learn from your letter of the second that the committee had decided to invite several other observatories in addition to the Yerkes Observatory. Inasmuch as the idea originated here with Professor Frost and all preliminary work of planning for it was conducted by him and Mr. Elvey, I would have expected the committee to inform us beforehand of such an important decision. I am also surprised that on page 2 of the release the Yerkes Observatory is named in the last place. Accordingly I do not understand just how the committee expects the Yerkes Observatory to play the principal role. Nor do I see any mention in the news bulletin of provisions for carrying the voice of the speaker from the Observatory to the Fairgrounds.

I take it that the decisions of our meeting of November 17, 1932 have been superseded by those of your letter of March 2, and we are really at a loss to know just what is expected of us. You will agree with me that as the last named of four observatories, line 2 from the bottom of page 2 and in line 17 from the top in page 5 of the news bulletin, our ardor is very considerably cooled because we feel that neither the first initiative nor the efforts on the part of Mr. Frost, Elvey, and myself have sufficiently been appreciated.

I have discussed the contents of this letter with Elvey and he thoroughly agrees with me.

We shall be glad to let you borrow the negatives which you will need for your transparencies.

Your very truly,

Otto Struve, Director

Transcription

I don’t know which one of my letters to the three additional participating observatories I sent to you in copy, but in whichever one it was you will note words to this effect: “Frost first suggested the plan and offered the facilities of the Yerkes Observatory to bring his plan to realization.” The only reason for extending participation to other observatories was the cloud hazard entailed in relying on a single one. I had proposed that Yerkes Observatory should be the only observing station, urging this limitation partly on the basis of expense on the part of the participating commercial companies. In case of clouds I had suggested postponement of the exercises, but when the expectancy of a crowd has been aroused by widespread public

announcement, postponement takes the edge off the thing and I concurred with the rest of the committee in the desire to broaden the participation to eliminate the cloud hazard.

I regret that you “feel that neither the first initiative nor the efforts on the part of Mr. Frost, Elvey and myself have sufficiently been appreciated.” I can assure you there is no lack of appreciation either of Mr. Frost’s original suggestion, for acknowledgement of this has been made on many occasions and I have insisted that he should have a vital part in the program here on the Exposition grounds. Nor has there been any lack of appreciation of his offer to put the facilities of the observatory to the furtherance of the plan, nor lack of appreciation in the interest and cooperation of his successor and Dr. Elvey. You state that you are “surprised that on page 2 of the release the Yerkes Observatory is named in the last place.” It is very common practice to name participants in an enterprise so that the most important shall stand as a climax at the end.

Very sincerely yours,

Philip Fox

Continuing Arcturus

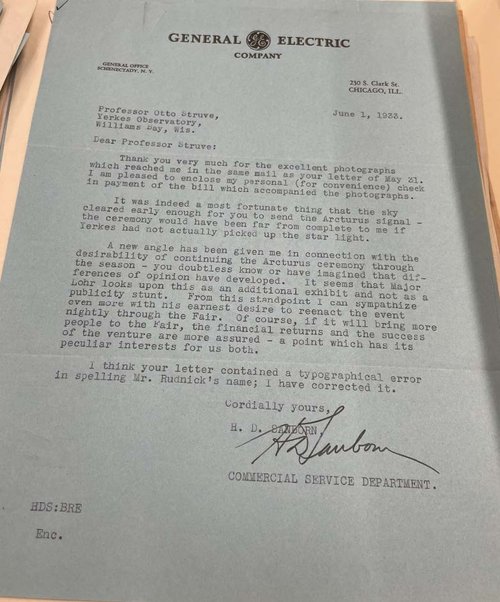

Debates between the Yerkes astronomers and the Century of Progress committee continued even past the Arcturus ceremony on May 27, 1933. Most of these debates surrounded the question of whether to continue the ceremony. After the success of the first stunt, the Century of Progress committee wanted to expand the lighting to happen every night, acting as a permanent exhibit in the fair. However, Yerkes scientists wanted the May 27th ceremony to be a one time occurrence, protecting its novelty and limiting the burden on Yerkes staff and instruments.

Here too, the clash between Century of Progress officials and Yerkes scientists demonstrates the differing priorities of the industrial and scientific communities of the early 20th century. In his letter, committee official H.D. Sanborn wrote that Yerkes should consider further support of the Arcturus exhibit not only to promote science education at the fair but also for “the financial returns” of the venture. Struve was uncompelled by Sanborn’s financial argument and instead posited that Yerkes should not spend time on commercial stunts but focus on pure scientific research. While the fair committee prioritized a commercialized science, Yerkes scientists consistently chose pure astronomical research.

H.D. Sanborn to Otto Struve on the potential continuation of the Arcturus exhibit, June 1, 1933. University of Chicago, Special Collections Research Center.

Transcription

June 1, 1933

Professor Otto Struve,

Yerkes Observatory,

Williams Bay, Wis.

Dear Professor Struve:

Thank you very much for the excellent photographs which reached me in the same mail as your letter of May 31. I am pleased to enclose my personal (for convenience) check in payment of the bill which accompanied the photographs.

It was indeed a most fortunate thing that the sky cleared early enough for you to send the Arcturus signal – the ceremony would have been far from complete to me if Yerkes had not actually picked up the star light.

A new angle has been given me in connection with the desirability of continuing the Arcturus ceremony through the season – you doubtless know or have imagined the differences of opinion that have developed. It seems that Major Lohr looks upon this as an additional exhibit and not as a publicity stunt. From this standpoint I can sympathize even more with his earnest desire to reenact the event nightly through the Fair. Of course, if it will bring more people to the Fair, the financial returns and the success of the venture are more assured – a point which has its peculiar interests for us both.

I think your letter contained a typographical error in spelling Mr. Rudnick’s name; I have corrected it.

Cordially yours,

H.D. Sanborn

Commercial Service Department

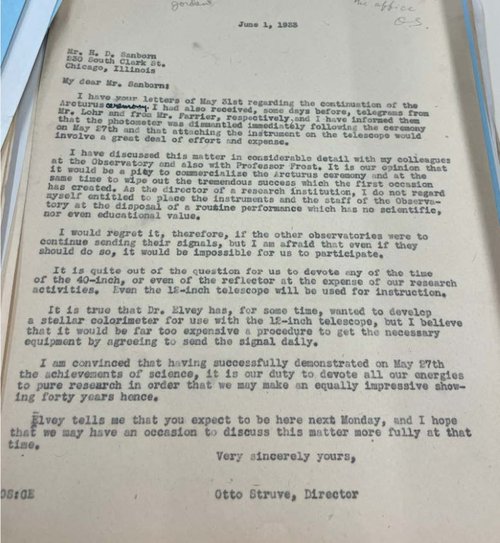

Otto Struve to H.D. Sanborn on the potential continuation of the Arcturus exhibit, June 1, 1933. University of Chicago, Special Collections Research Center.

Transcription

June 1, 1933

Mr. H.D. Sanborn

230 South Clark St.

Chicago, Illinois

My dear Mr. Sanborn:

I have your letters of May 31st regarding the continuation of the Arcturus ceremony. I have also received, some days before, telegrams from Mr. Lohr and from Mr. Farrier, respectively, and I have informed them that the photometer was dismantled immediately following the ceremony on May 27th and that attaching the instrument on the telescope would involve a great deal of effort and expense.

I have discussed this matter in considerable detail with my colleagues at the Observatory and also with Professor Frost. It is our opinion that it would be a pity to commercialize the Arcturus ceremony and at the same time to wipe out the tremendous success which the first occasion has created. As the director of a research institution, I do not regard myself entitled to place the instrument and the staff of the Observatory at the disposal of a routine performance which has no scientific, nor even educational value.

I would regret it, therefore, if the other observatories were to continue sending their signals, but I am afraid that even if they should do so, it would be impossible for us to participate.

It is quite out of the question for us to devote any of the time of the 40-inch, or even of the reflector at the expense of our research activities. Even the 12-inch telescope will be used for instruction.

It is true that Dr. Elvey has, for some time, wanted to develop a stellar colorimeter for use with the 12-inch telescope, but I believe that it would be far too expensive a procedure to get the necessary equipment by agreeing to send the signal daily.

I am convinced that having successfully demonstrated on May 27th the achievements of science, it is our duty to devote all our energies to pure research in order that we may make an equally impressive showing forty years hence.

Elvey tells me that you expect to be here next Monday, and I hope that we may have an occasion to discuss this matter more fully at that time.

Very sincerely yours,

Otto Struve, Director