Unfolding Before Your Eyes

Imagine gathering in the dark, by torchlight and candle, to listen to the story of a hero, sung and intoned by performers and musicians, and illustrated by holding an oil lamp to just a small part of this vast painted cloth. That is how this painted textile from the Indian state of Rajasthan would have been used in nighttime performances that tell the story of Pabuji, a deified folk hero. Pabuji is the large central figure seated on the throne. He is said to have lived in the fourteenth century, and is remembered as the king who first brought camels to Rajasthan.

The painted scroll, or phad, is considered a sacred object by those who worship Pabuji. Itinerant priests and performers, known as bhopas (male) and bhopis (female), traditionally traveled from village to village with their instruments and painted scroll . The phad is the illustrative backdrop for the story told by the bhopas, who describe their performance as "reading the phad." Episodes from the epic of Pabuji are arranged on the scroll according to where, and not when, they occurred. Thus, the same figures are repeated in various parts of the painting, though each iteration represents a different point in time.

The scroll is a portable icon, unfurled only for performance, and only during the auspicious months of the year. Rituals invite Pabuji to inhabit the sacred scroll, making the performance an act of worship and divine viewing (darshan). The performance will last all night, concluding in the early hours of the morning.

Warli Paintings

Paintings of this type originated in Western India in present-day Maharastra, and are named for the indigenous communities that developed this style. Warli paintings were originally executed on the walls of buildings, in white pigment made of rice paste and gum on reddish-brown mud walls, for festivals such as the harvest or a wedding.

The large painting here depicts a dance around a long horn-shaped instrument known as the tarpa, which we see at the center of the circle of dancers. Paintings on this theme are hence known as Tarpa Dance paintings. As in all Warli paintings, geometric shapes, such as the square, triangle, and circle, figure prominently in the design of the figures and overall composition of the painting.

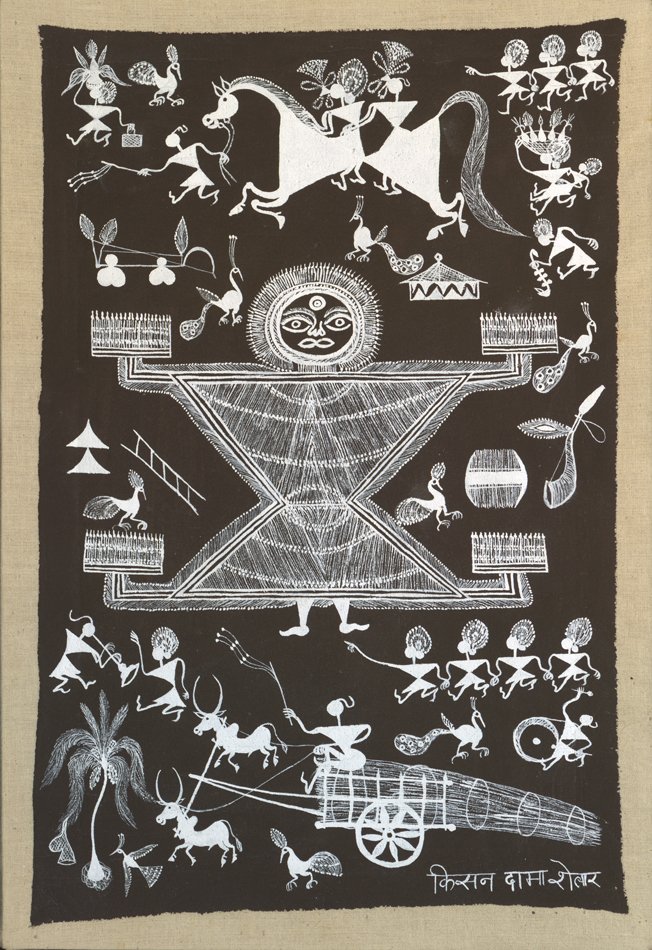

Warli paintings are distinctive for their use of geometric shapes and patterns. The painting of Palghat Devi, the goddess of marriage, features a large image of the goddess whose body is composed of two triangles, one inverted on the other. The bride and groom are shown at the top of the painting, galloping away on a white horse. Peacocks, musicians, and a cart pulled by a pair of bullocks decorate the village scene. This is a popular composition and subject, and would have traditionally been painted at the bride's house at the time of marriage.

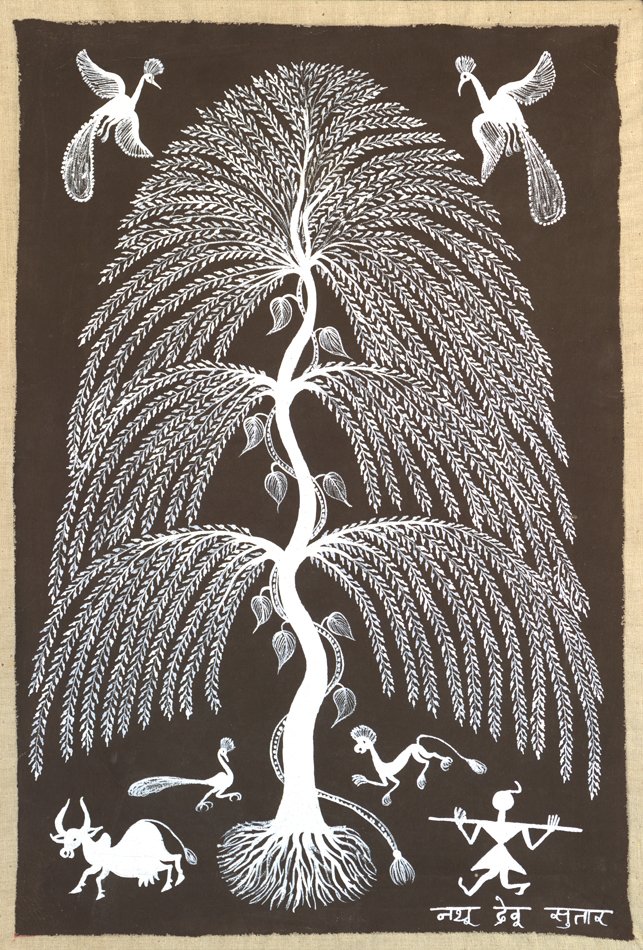

Trees, surrounded by animals, are another popular theme in contemporary Warli painting. Here, two flying peacocks frame the upper part of the tree, while a cow, its keeper, and other animals shelter at its base.

Until the 1970s, Warli painting was a women's art. At that time, the support of the Handicrafts Board and the growing tourist trade led to greater interest in Warli paintings, and to a rejuvenation of the art form. Men also began to produce paintings in this style, and some became well known artists in their own right. That each of the three paintings bears the artist's signature in the lower right corner is a testament to the commercialization of this tradition. Nathu Devu Sutar painted the Tarpa Dance and the tree, while the image of Palghat Dev is signed by Kisan Dama Shelar.