Education Out of Incarceration

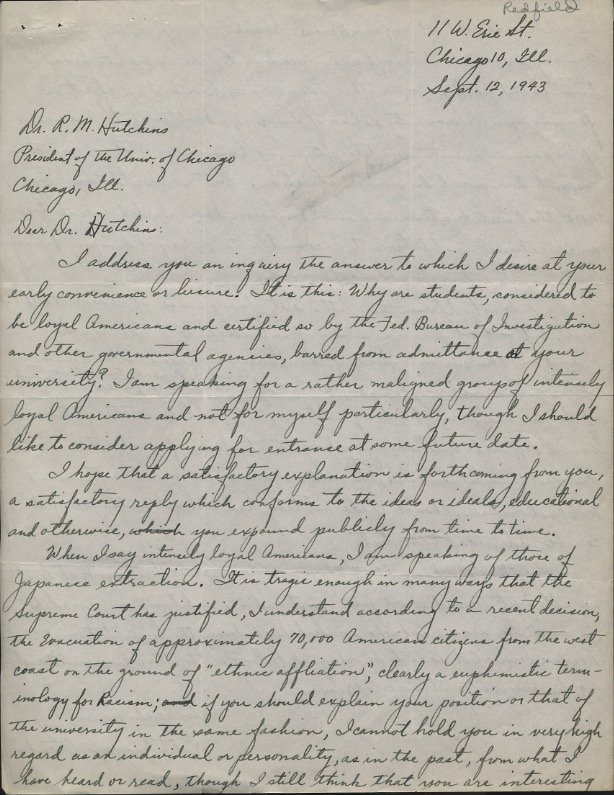

For young forcibly interned Japanese Americans, going to college was both freedom and a tangible way to create a future in America. Unfortunately, for most of World War II, the gates of the University were closed to Japanese Americans.

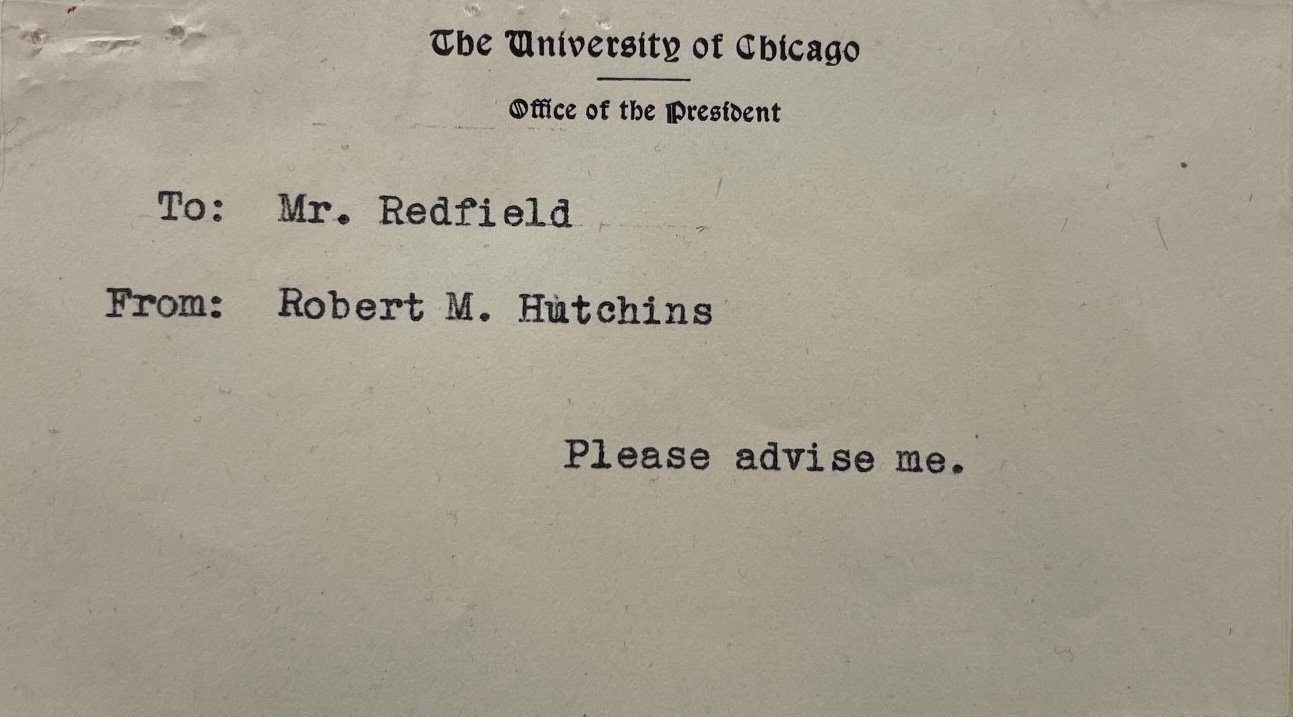

In June 1942, University President Robert M. Hutchins found that it was “deemed inadvisable” to accept Japanese Americans due to the “extensive naval and military work” at the University (Redfield, June 17, 1942). After this initial self-imposed policy, the University found it increasingly difficult to continue to reject prospective students based only on their Japanese ancestry. In response to one request dated February 9, 1943, President Hutchins wrote to Royal H. Fisher that he wished he “could do something…[but] we are, for all practical purposes, a military reservation.”

As the war progressed, hundreds of Japanese Americans enrolled at other colleges in Chicago and thousands moved to Chicago’s South Side, but the restrictions continued. Here, a selection of documents which capture reactions from the campus community, administrators, and Japanese Americans is presented.

I think this restriction placed by military authority upon our freedom to admit Japanese-American students is both unwise and unjust. Nevertheless it exists.

Robert Redfield, Dean of the Social Sciences

Office of the President, Hutchins Administration Records, the University of Chicago

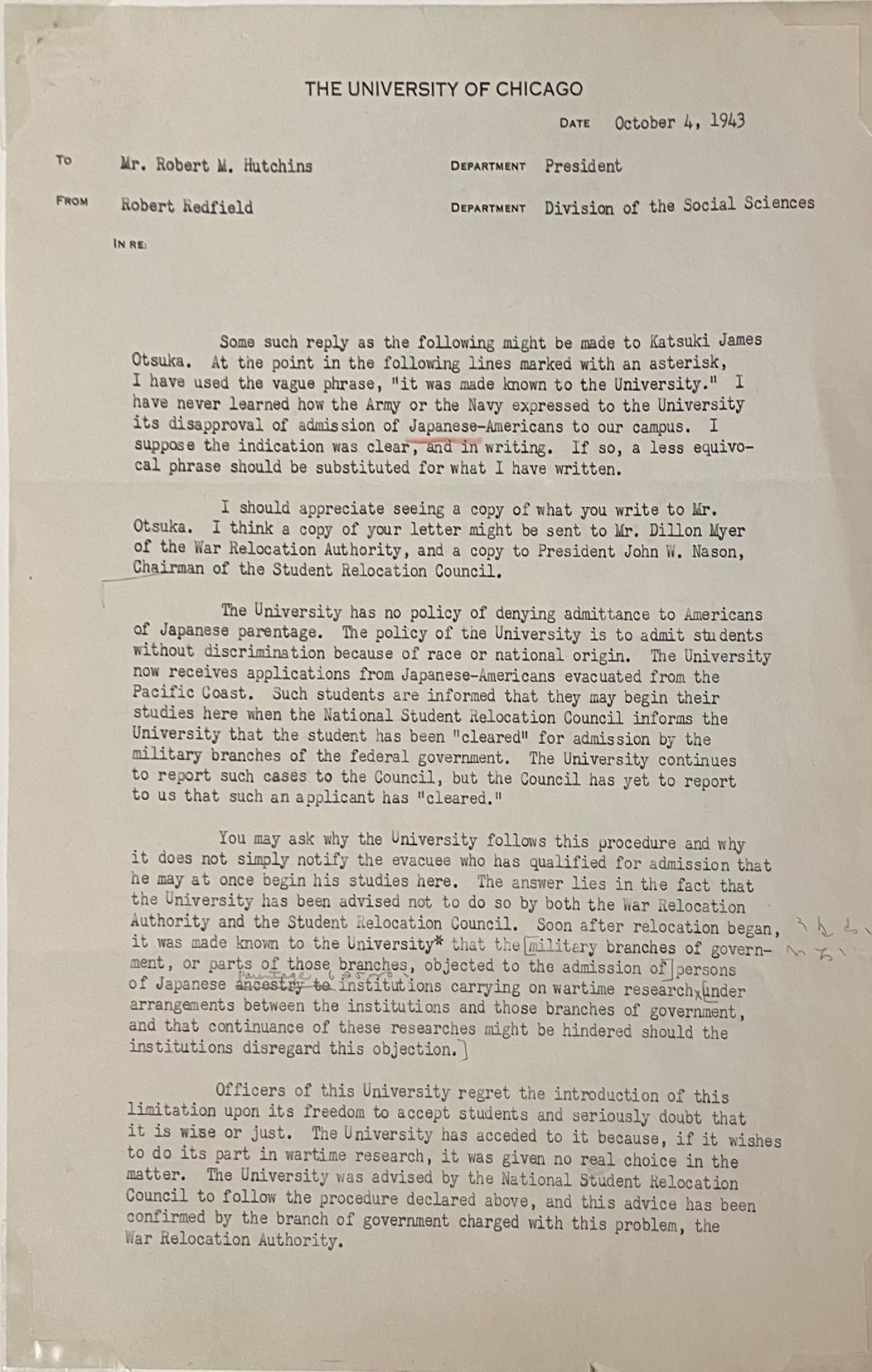

Three months later, Vice President Emery T. Filbey would respond that:

“officers of this University regret the introduction of this limitation upon its freedom to accept students and seriously doubt that it is wise or just. The University has acceded to it because, if it wishes to do its part in wartime research, it was given no real choice in the matter…that the temporary exclusion of certain Americans of Japanese origin from student privileges is not an expression of University policy, but is something imposed upon it.”