The Civic Spirit

An

Era of Institution-Building

Although the impetus for the University's creation came from the Baptist churches of Chicago and the Middle West, along with an endowment from John D. Rockefeller, its growth and expansion depended heavily on local businessmen and their families. By the 1890s Chicago business had come of age, and a generation of merchants and financiers were turning their attention to building cultural institutions in the city. As Chicago's literary magazine, the Dial, proclaimed, "the signs are clear that the season of mere physical life is over, and that the life of the soul calls for exercise and nourishment." Men who came together to sponsor the World's Columbian Exposition learned to cooperate on other ventures, including the Art Institute, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and a new university.

The University of Chicago was one of many institutions created or enlarged in the 1890s. Older organizations such as the Historical Society and the Academy of Sciences had been formed by and for members of genteel society who valued culture; now the emphasis was on institutions which could raise the standards of the public at large. The University's role was to promote the finest scholarship in all fields of human knowledge.

Martin A. Ryerson and Charles L. Hutchinson served concurrently for nearly three decades as president and treasurer of the University's Board of Trustees. Sons of pioneer Chicago entrepreneurs, they were especially concerned with bringing refinement and "civilization" to a city which still had the rough face of a frontier town. Through an interlocking series of boards and committees, Ryerson and Hutchinson with their friends sponsored churches, asylums, hospitals, museums, libraries, schools, and all the other accoutrements Chicago needed to become a world-class city.

Hutchinson inherited his

father's holdings in the Chicago Packing and Provision Company, the

Chicago Board of Trade, and the Corn Exchange Bank. A conservative investor,

he was widely trusted by other businessmen. His travels to Europe convinced

him that Chicago should be improved with artworks and other public institutions

to raise people's consciousness of higher ideals. Hutchinson spent much

of his time and nearly half his income on philanthropic endeavors, helping

to found the Art Institute and later serving as its president; serving

as a director of the World's Colombian Exposition and the Chicago Relief

and Aid Society, trustee of Presbyterian Hospital, Chicago Lying-In

Hospital, and Hull house, treasurer of the Immigrants' Protective League,

and president of the Chicago Orphan Asylum; and helping to secure a

site for the Field Museum of 6atural History. Active in the Commercial

Club, Hutchinson also helped organize the Chicago Athletic Club and

the Cliff Dwellers, all the while also being an active member of St.

Paul's Universalist Church.

Taking over his father's lumber business, Martin A. Ryerson shared Hutchinson's vision of the ideal city and worked closely with him through much of his life. An avid collector and student of art, he served as vicepresident of the Art Institute and of the Field Museum and also supported the Chicago Orphan Asylum, the Sprague Memorial Institute, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Poetry magazine. Ryerson had funded the physics laboratory for the University, and his highminded approach to science was expressed in his speech at the dedication of the Yerkes Observatory in 1897, when he encouraged "the cultivation of science for its own sake" at a time when so much energy was expended on "the improvement of material conditions."

University fundraisers sometimes had to compete with counterparts from other organizations. In a sense, though, each institution lent prestige to the others, as each benefited the city as a whole. William R. Harper sought close associations with other educational organizations in the city. Some affiliated directly, such as Rush Medical College, the Chicago Manual Training School, and many years later the John Crerar Library; some discussed mergers or cooperative ventures but remained independent, as did the Armour Institute of Technology and Theodore Thomas's Chicago Orchestra. Others maintained close ties through individual trustees or faculty members, as did the Art Institute and Field Museum. Interaction among the city's educational and cultural institutions strengthened them individually and collectively, as each developed a unique identity and purpose.

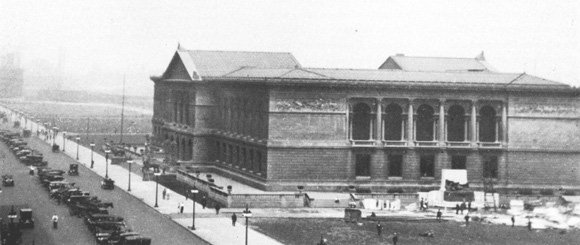

Trustees of the Art Institute cooperated in building a hall for the congresses held in conjunction with the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, and after the conclusion of the fair used it to house the growing art collections.

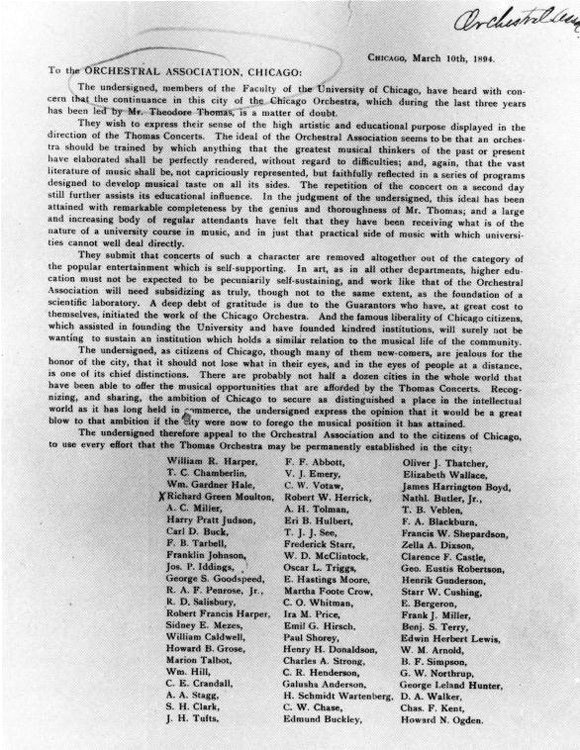

Sixty-nine faculty members expressed their support for the recently established Chicago Orchestra, insisting it was important for art and education, not merely a "popular entertainment." Signers came from all parts of the University, including zoologist Charles Otis Whitman, mathematician Eliakim Hastings Moore, Divinity School professor Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, dean of women Marion Talbot, and football coach Amos Alonzo Stagg.

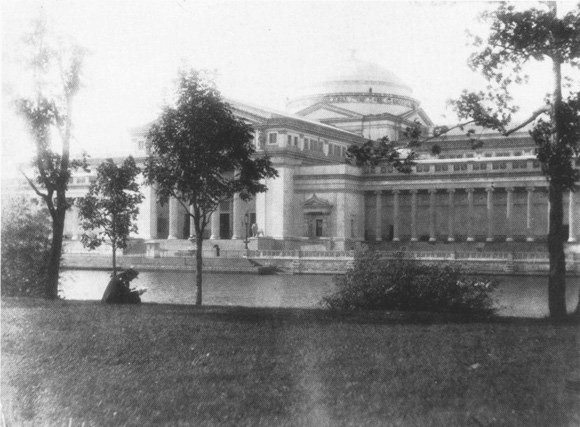

Exposition continued in use as the first home of the Field Colombian Museum, later renamed the Field Museum of Natural History. When the Field Museum moved to a new site at the south end of Grant Park, the building was refurbished and reincarnated as the Museum of Science and Industry.