Edges of the Academy

Infamous for its intense intellectual rigor, scholarly life at the University of Chicago has been stereotyped as totally serious and at times even pretentious. With unparalleled academic achievements and eighty-seven Nobel laureates, some might simply say that the stereotype is justified, but students and faculty confront their reputation with lightheartedness. Students wear t-shirts with slogans such as “Where fun comes to die” that poke fun at their own seriousness and participate in many activities beyond the confines of the classroom, such as the Scavenger Hunt and Kuvia, a week-long January festival in which students wake up at 5 a.m. to do calisthenics with the Dean of Admissions. Although the Middle Ages and Renaissance were periods of spiritualism and scholarship, these manuscripts demonstrate both the serious and the playful elements in study and devotion in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Darren Leow, Class of 2012

The Latke-Hamantash Debate is an annual proceeding in which professors argue for the merits of one or the other traditional item of Jewish holiday food. The debate originated at the University of Chicago in 1946 to celebrate Jewish contributions to the academy at a time when they were often marginalized, as well as to spoof the seriousness of academic disputes.

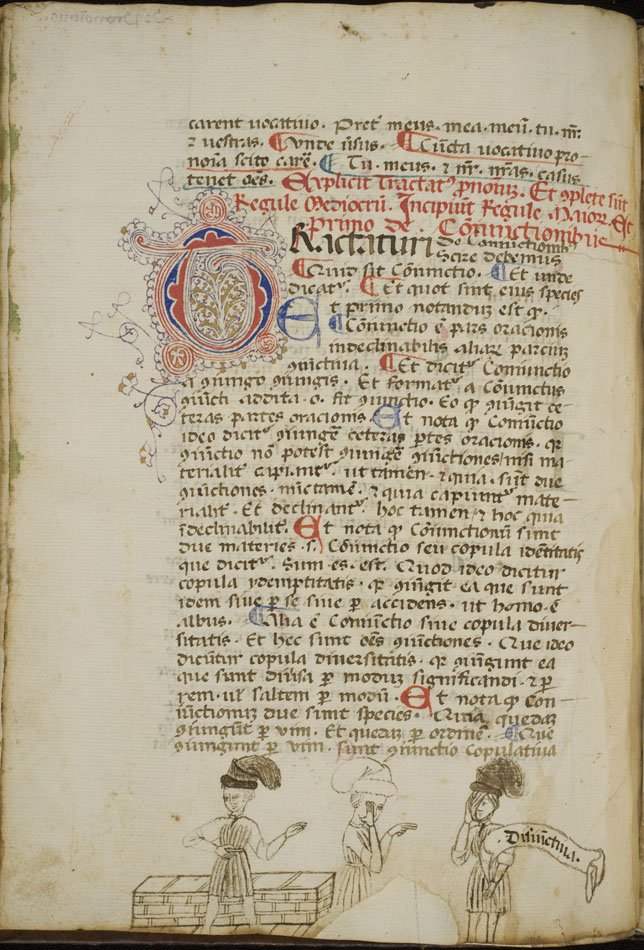

Italy, ca. 1390-1400

Paper

MS 99, ff. 79v-80r

This manuscript is a textbook of Latin grammar and rhetoric, probably written for a student of Francesco da Buti(1324-1406), Professor of the University of Pisa. The artist/scribe created penand- ink drawings around catchwords to enhance the learning process. Each catchword is incorporated into a drawing that makes a joke out of the catchword. Here a drawing puns on the catchword “disiunctiva,” which meant separative and in the context of grammar designated a conjunction that indicates parallel but logically unrelated phrases. The artist has drawn a wall to indicate the idea of separation, but has also drawn three figures pointing to their swollen eyes. “Coniuntiva,” or as we know it, conjunctivitis, is the ailment of ocular swelling. The artist has linked the technical term “disiunctiva” and its meaning of separation with the memorable idea of “coniuntiva” and its humorous representation in order to aid the student’s retention.

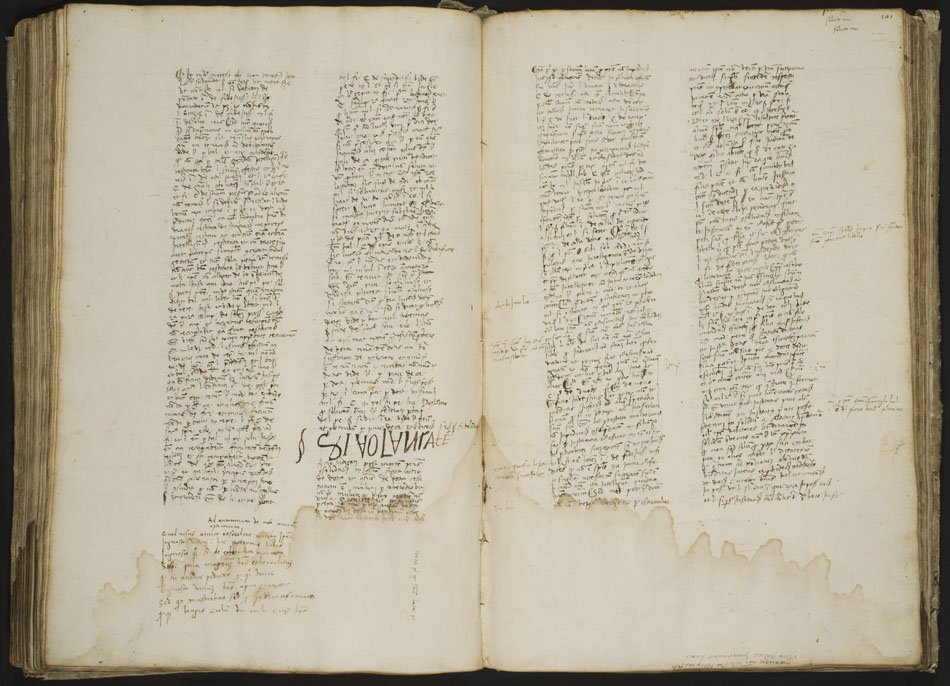

Antonius de Raho

Italy, 1482

Paper

MS 37, f. 100 v

This manuscript on paper contains commentaries on Justinian’s Digest dealing with divorce settlements and wills by Antonio de Raho, a Neapolitan jurist and professor of law. It was originally a lecture book for de Raho’s personal use or a student’s copy. The central text was probably written in de Raho’s own hand and ample space is left for annotations. Notes appear throughout the manuscript, typically observations about the content of the text, but a salacious poem is written in the bottom left margin of this opening in a hand contemporary with de Raho. Beginning, “To Antonio de Raho, best friend,” the poem proceeds to mock de Raho for taking himself too seriously, musing on his sexual proclivities.

Ad antonium de raho amicum optimum

Quod nescis amico rescribere versibus ipse

Ignosco vitium: hoc cicerones habes

Ignosco quoque si de etheroclita norma

S ( ) quia magistrum habes etheroclitum

Quod tu cunctos pedicas quod quoque duros

Ignosco vitium habes ( )

Sed quod masturbas sed quod pedicaris amice

Quodque lingis culum dic mihi cuius habes

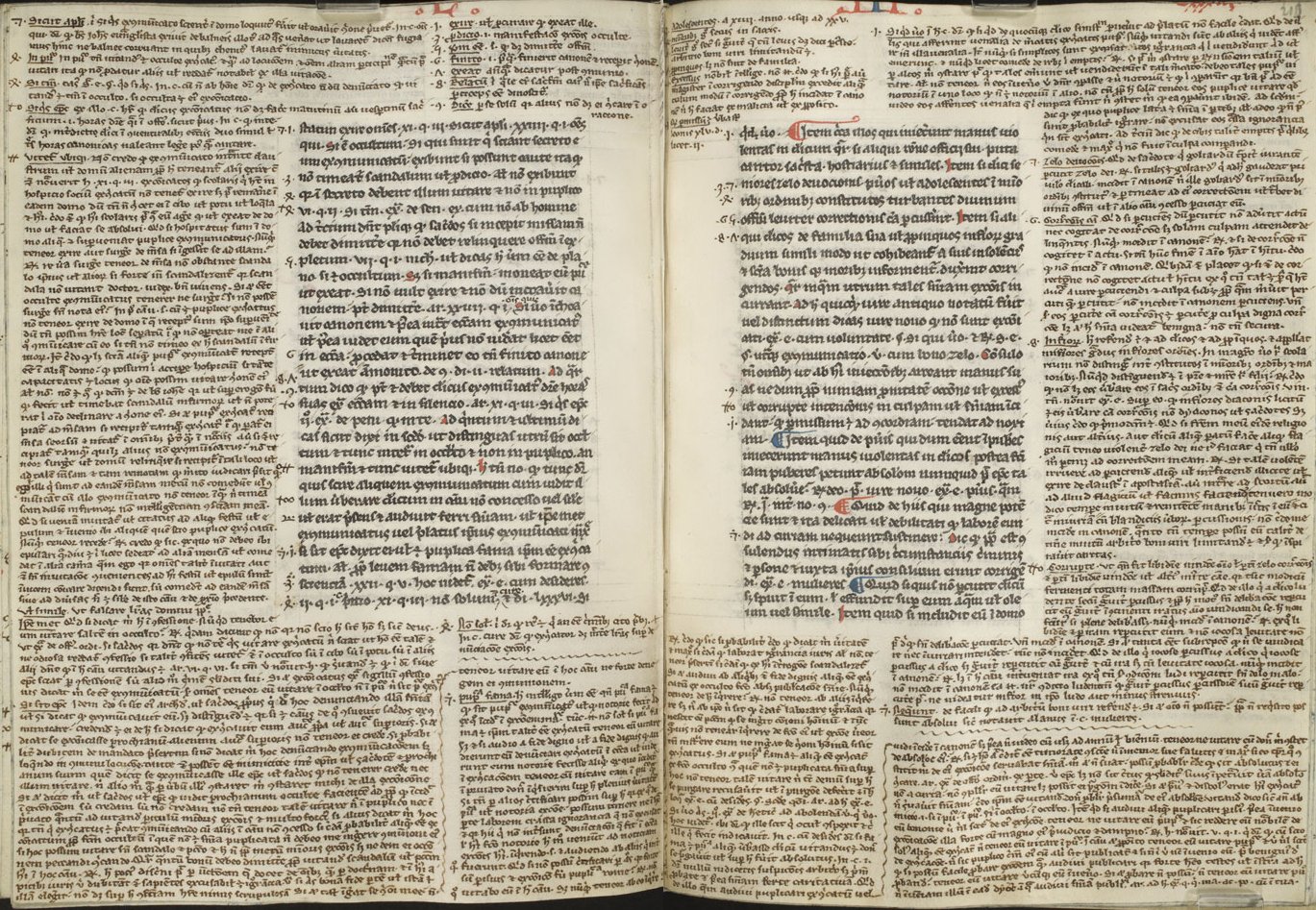

Raymond de Penaforte and Wilhelm of Rennes

France, ca.14th century

Ms. 185, ff. 115v-116

This fourteenth-century manuscript contains Catalan Dominican friar Raymond of Penafort’s Summa de poenitentia et matrimonio, a major work on the subject of penitence and matrimony. The intricate and complex design of this page is a typical layout in which a marginal gloss surrounds, interprets, and expands the main text. The single column of the main text by Raymond of Penafort is engirded on three sides by a copious commentary by theologian Wilhelm of Rennes. Written in a minute and heavily abbreviated script, the commentary overwhelms the central text, shifting visual and perhaps intellectual precedence to the edges.

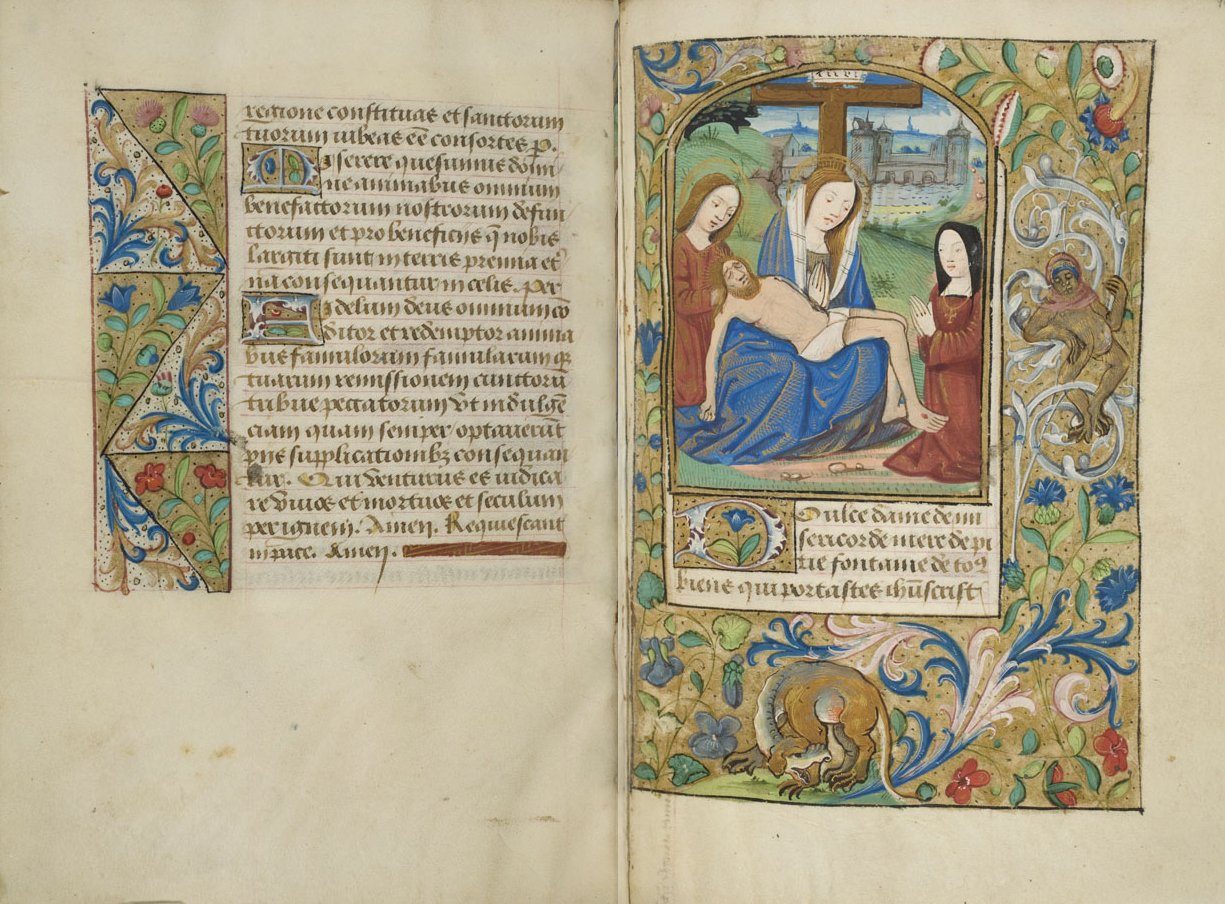

France, ca. 1500-1510

Parchment

MS 343, ff. 89v-90r

Books of Hours were prayer books that enabled personal devotion in the Middle Ages. Here we see the Virgin Mary draped in blue robes, her eyes solemnly cast upon the body of Christ. Two red-robed figures flank the mother and son; Saint John kneels on the left, a woman wearing a gold cross and black wimple kneels on the right. The female figure represents the intended owner of this Book of Hours. Patrons often commissioned illuminations featuring their portraits, sometimes inside the miniature or in the margin. A female owner contemplating this image might meditate upon the grieving Virgin, seeking to emulate Mary’s virtuousness. In the right margin stands a monkey wearing a headdress, which is significant because monkeys often appeared in margins to mock mankind’s base nature. While this monkey’s downcast eyes and attire mirror the Virgin, he ridicules the book’s owner, not Christ’s mother. Like the monkey, the book-owner is a fallible creature with animal desires. As she attempts to emulate the Virgin, she is more akin to the clothed beast than the Queen of Heaven.