Demonizing the Enemy

Another driving force during the revolutionary period was the demonization of both real and perceived enemies. The Pahlavi monarch was the main target of antagonistic protest chants, graffiti slogans, and leaflets distributed during the revolution. After the U.S. Embassy was stormed by a group of young Islamist radicals on November 4, 1979, however, attention also turned towards the United States (nicknamed “the Great Satan” in Iran). Together with the United Kingdom, the U.S. was seen as the real power behind the Pahlavi monarchy and was still resented by Iranians for the 1953 CIA-led coup d’état that overthrew the democratically elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq.

Demonization is a means of differentiating oneself from a perceived enemy, thereby creating an oppositional axis of “good” vs. “evil” symbolically titled in one’s favor. Through the process of rhetorical and visual defamation, the Islamic Republic’s rivals were publicly mocked in order to neutralize their ideological threat as well as to create a semblance of consensus among Iranians of divergent political opinions during and after the 1979 Revolution.

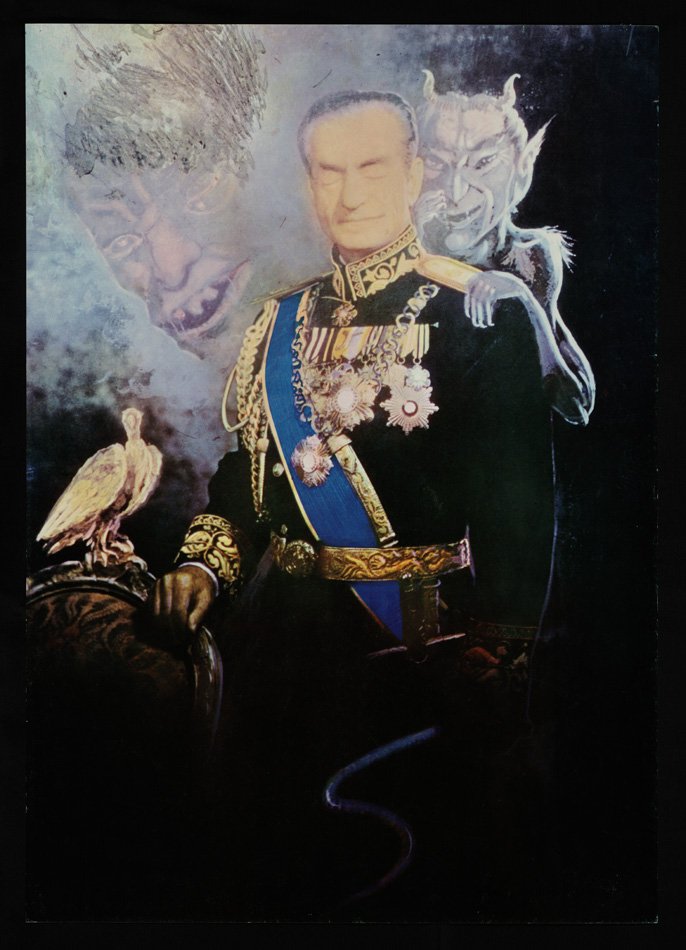

During the Revolution, leaders and protesters of the revolutionary movement demonized Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, accusing him of corruption and theft. The Iranian monarch was the main target of antagonistic protest chants, graffiti slogans, and political posters, in which he was depicted as a slithering worm and a demonic spirit.

The U.S. was characterized in Khomeini’s speeches and the Islamic Republic’s propaganda as a decadent and corrupt imperialist nation. By depicting the U.S. as the moral antithesis of the Islamic Republic, Khomeini and his supporters aimed to capitalize on the Iranians’ approval of the U.S. hostage crisis, while simultaneously galvanizing the populace to identify with the Islamic Republic and its mission.

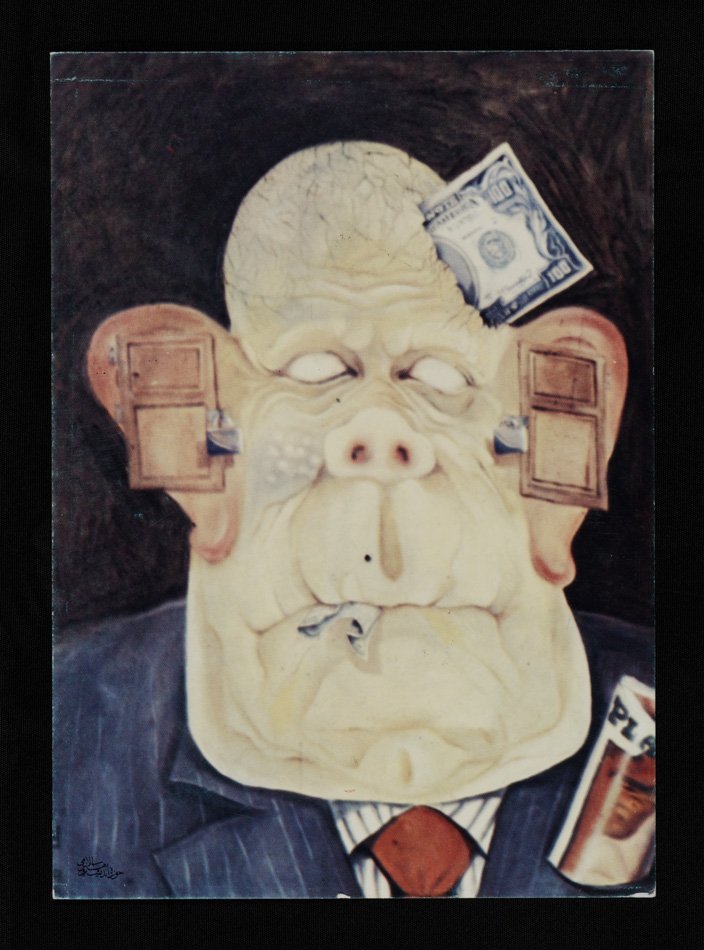

Images produced at the height of anti-U.S. sentiment include, for example, postcards of a corrupt and grotesque President Carter, with ears locked shut and money shoved into his head and mouth. Such images served to vilify the American government and to underscore the moral decadence of capitalism.

After the Islamic Republic was formed, a number of other opponents (both real and imagined) to the new nation were similarly vilified and denounced. For example, the United States was decried as a morally corrupt and imperialist power, whose influence within Iran had to be countered in one fashion or another. During the Iran-Iraq War, Iraq’s secular leader, Saddam Hussein, also was demonized by means of satire, caricature, and animal allegory.

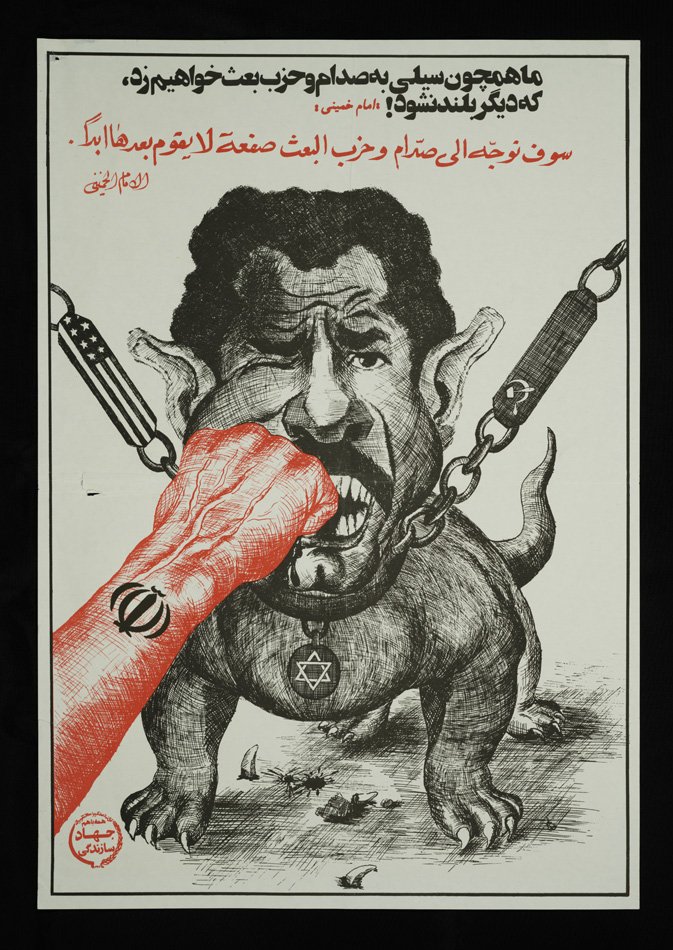

The other recipient of post-revolutionary animosity was Saddam Hussein. Khomeini hoped to inspire other Islamic revolutions across the Middle East, including in Iraq, where Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime ruled over the largely Shi’a population of Iraq with an iron fist. One poster of Saddam Hussein produced in Iran around 1980 shows him as a growling bulldog leashed in by the Soviet Union, the U.S., and Israel, to be defeated by the collective punch of the Iranian people’s striking fist. By depicting Saddam as merely an attack dog of foreign world powers, the poster insults him and diminishes the danger posed by the Iraqi leadership, while predicting its eventual destruction by the Islamic Republic.

In September 1980, Saddam Hussein, feeling threatened by the Islamic Republic’s attempts to incite the Iraqi Shi‘a majority to overthrow his leadership and seeking to take advantage of the revolutionary chaos in Iran, ordered the invasion of Iran. Thus began the eight-year Iran-Iraq War.

ca. 1980

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 3, Poster 163

In this poster, Saddam Hussein is satirically portrayed as a growling dog held by both American and Soviet leashes, with a dog tag bearing the Star of David hanging from his collar. The red fist of Iran punches Saddam in the face, knocking several teeth out onto the ground. Iranians considered Saddam a puppet of the United States and the Soviet Union. The work is rendered in a block print style, and was commissioned by the Jihad-i Sazandegi, or Wartime Ministry. The bilingual Persian-Arabic inscription states: “We [Iranians] will punch Saddam and the Ba’thist Party so hard that they will never rise again.” The poster predicts a collective victory for Iran.

ca. 1978–1980

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 3, Poster 164

In this poster, a formal portrait of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in full military regalia has been altered to show him as under demonic influence. His eyes have been painted shut, suggesting his total blindness to the needs and desires of Iranians, as well as his obliviousness to the uprising that will soon overthrow his rule. By altering a portrait of the Shah to show him as under the influence of demonic creatures, the image implies, by contrast, the piety and righteousness of the Islamic revolutionary spirit.

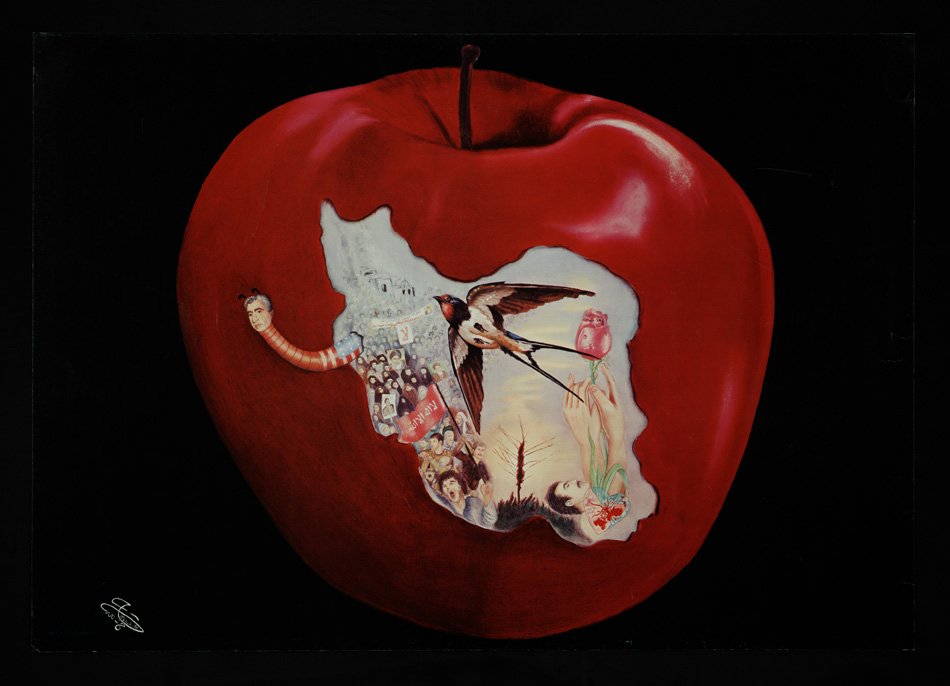

1979

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 4, Poster 177

This poster presents Iran as an apple with the shape of the country stretched across the fruit’s red skin. Within the nation’s outline, a large protest march represents the Revolution. A swallow, flying as dawn breaks across the sky, symbolizes a new day for Iran. A tulip encircled with two hands in prostration sprouts from the stylized heart of a man killed during the overthrow of the Pahlavi regime, a remembrance of those who died for Iran’s freedom. The Shah, depicted as a worm wearing the U.S. Flag, slithers out of Iran. This poster’s style is noticeably surrealistic, and thus not as influenced by Shi’i religious iconography as subsequent Iranian political art.

1979

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 1, Poster 12

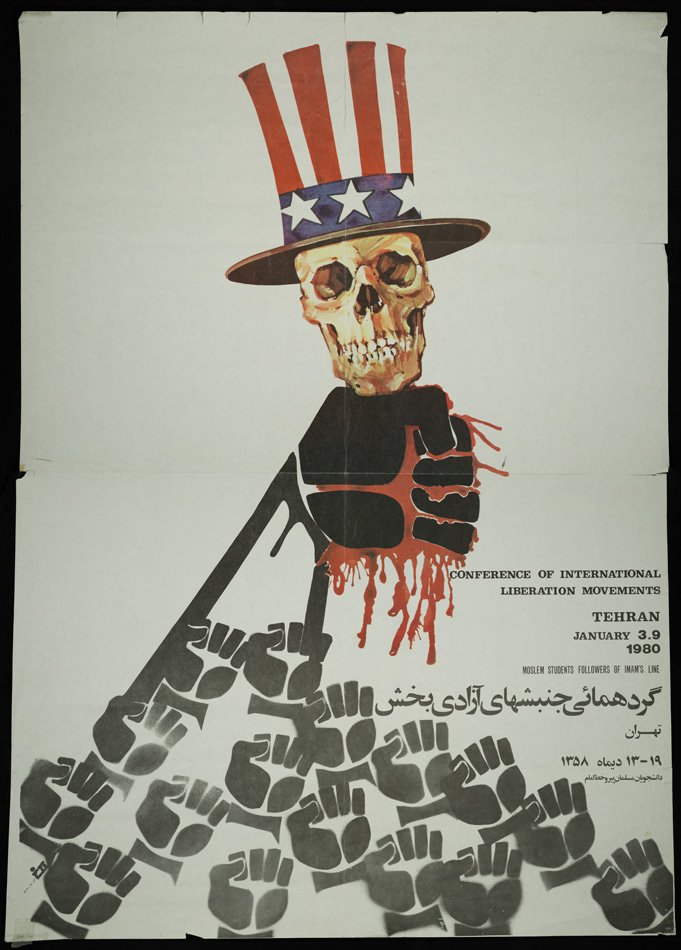

During the Revolution, American icons were often used to demonize and symbolically threaten the United States. Khomeini and many other Iranians considered the US an enemy of the opposition movement as evidenced by the CIA-sponsored coup of 1953, which resulted in the return of the Pahlavi monarchy that many Iranians viewed as a puppet government propped up by the United States and Great Britain. The recognizable top hat of Uncle Sam is drawn atop a human skull that is being crushed by a large fist. The fist, a common symbol of revolution and revolt, shows the influence of Russian and Latin American revolutionary graphics on Iranian revolutionary imagery. Commissioned for the Conference of International Liberation Movements in Tehran, this poster seems to argue for the power of collective action to defeat American hegemony. Such symbolic depictions of the United States were used to galvanize Iranians against the so-called “Great Satan.”

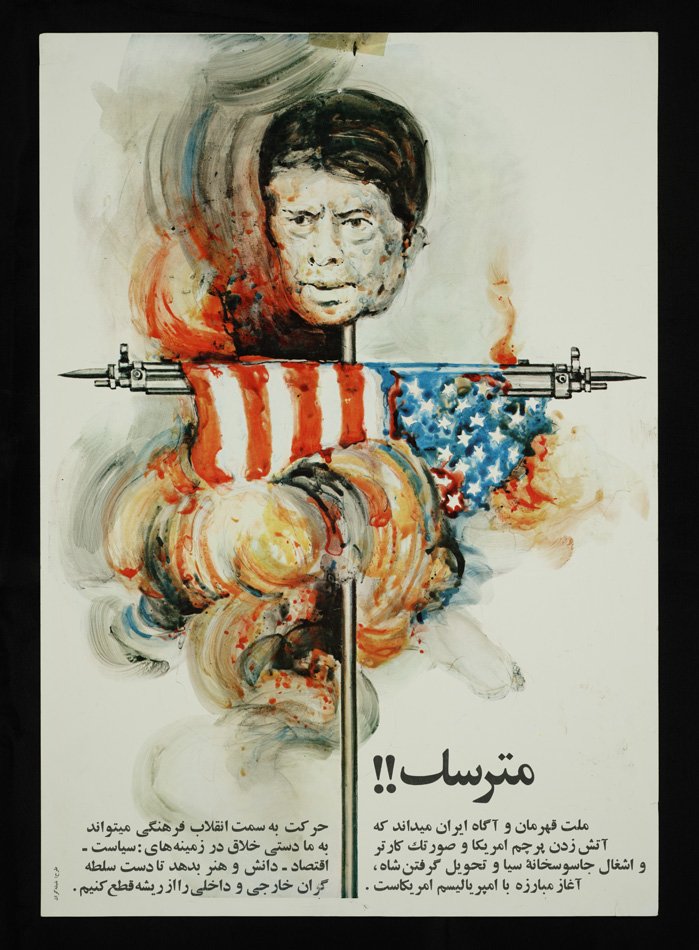

ca. 1980

Kourosh Shishegaran, Iranian, b. 1945

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 3, Poster 145

An effigy of President Jimmy Carter is being burned as part of the anti-U.S. protests that took place outside of the U.S. Embassy during the Iranian hostage crisis. During the siege of the “Den of Spies,” as Iranians called the Embassy, crowds burned straw effigies of President Carter in the same manner as the ritual burning of effigies of ‘Umar during ‘Ashura processions. Shi’is believe that ‘Umar, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad, usurped the right to rule from Imam ‘Ali during the succession crisis after the Prophet’s death. By casting President Carter in the role of traitorous ‘Umar, this poster symbolically blends Shi’i religious rituals with political demonstrations, a religio-political fusion that marked the Iranian Revolution.

1979

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 3, Poster 94

With his face grotesquely exaggerated, President Jimmy Carter is represented in this small caricature as a vulgar, pig-nosed businessman. His large ears are locked shut and his eyes are blind, while a one hundred dollar bill sticks out from his head, and a rolled-up Playboy magazine is stuffed into his business suit pocket. By portraying Carter as deaf and blind to everything except the lure of money and sex, the caricature emphasizes the moral corruption of the enemy and, by contrast, the righteousness of the Iranian Revolution.

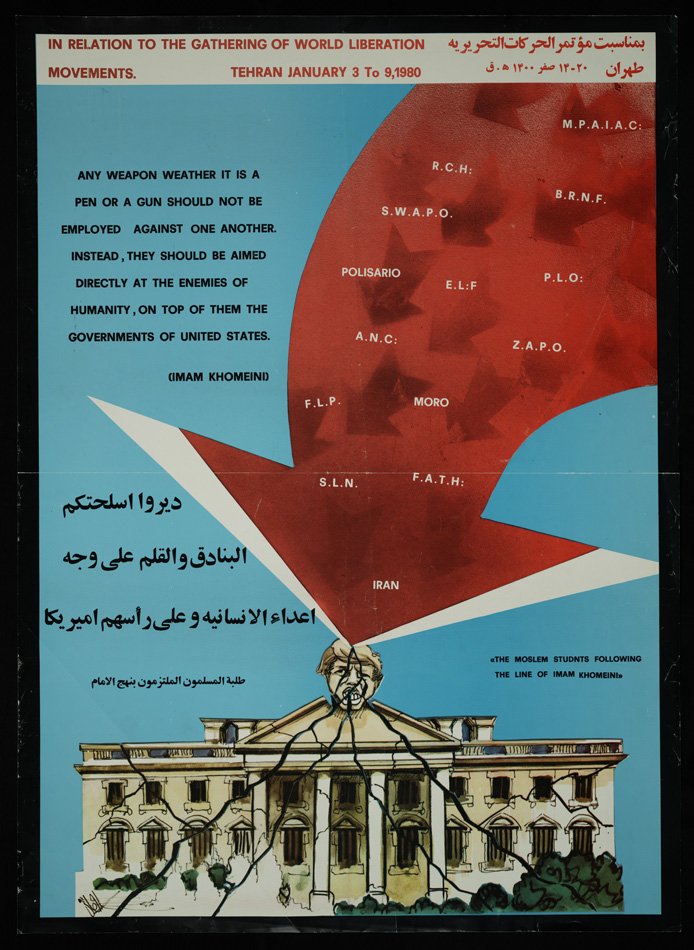

January, 1980

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 4, Poster 212

In an advertisement for the gathering of world liberation movements, a large red arrow with acronyms of various parties and liberation movements led by Iran descends upon President Carter and the White House. Much like a collective fist, the arrow touches and immediately breaks a bust of Carter, simultaneously cracking the building to its very foundations. Khomeini hoped that the Iranian Revolution would spread across the Islamic world, emboldening other Muslims (in Saudi Arabia and Iraq most especially) to overthrow their U.S.-backed and European-supported governments.

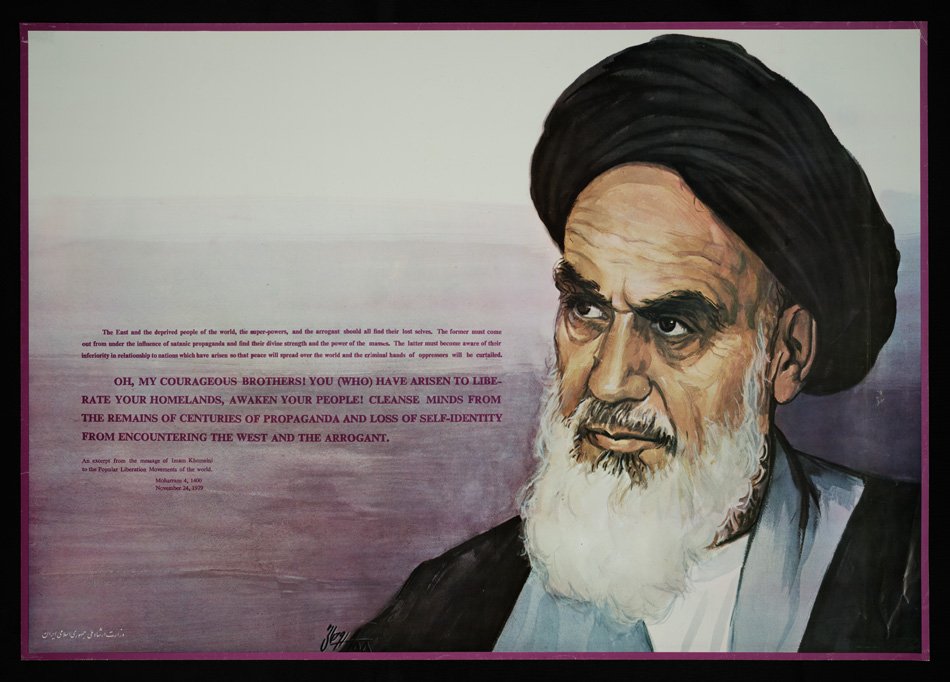

1979

Middle Eastern Posters Collection

Box 2, Poster 57

A portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini is paired with an excerpt from a speech he delivered in November 1979, translated into English. Speaking to the popular liberation movements of the world, Khomeini criticized the history of foreign colonialism and interference in the Islamic world. Because the Pahlavi regime controlled all printing presses before the revolution, posters of Khomeini were used as vehicles of dissent that also served to disseminate the religious leader’s revolutionary message during his exile.