Exhibition Catalog: Essay and Didactics

Introduction

For over one hundred years, posters have acted as effective tools to disseminate various ideological messages during periods of revolution and war. Designed for mass distribution and aimed towards a large public audience, they embed social, political, and religious concerns that frequently are articulated through both text and image. Perhaps more so than at any other moment in recent history, posters served as powerful modalities for mobilization and communication during the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88).

Visualizing a Revolution

The 1979 Iranian Revolution was in many respects the culmination of repeated attempts throughout the twentieth century to install a democratic government in Iran. However, the definitive overthrow of the monarchy began in earnest in October 1977 with the death of Ayatollah Khomeini’s son, Mostafa, rumored to have been assassinated by security services. The first round of anti-government protests began in the religious city of Qom and slowly spread throughout Iran. From the uprising’s earliest days, Iran’s Pahlavi monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah, attempted to stifle public dissent, which resulted in several civilian deaths.

Following the Shi’ite custom of commemorating the deceased forty days after their death, activists organized mourning ceremonies across the country in honor of the slain protesters. These public ceremonies became the loci from which further protests developed. Growing exponentially, the cycle of violence and lamentation threw Iran deeper into chaos, which, eventually, turned into a nationwide civilian uprising. Public sentiment continued to grow against the Pahlavi regime in August of 1978, when a fire was set that burned down the Cinema Rex in Tehran, killing over four hundred people trapped inside.

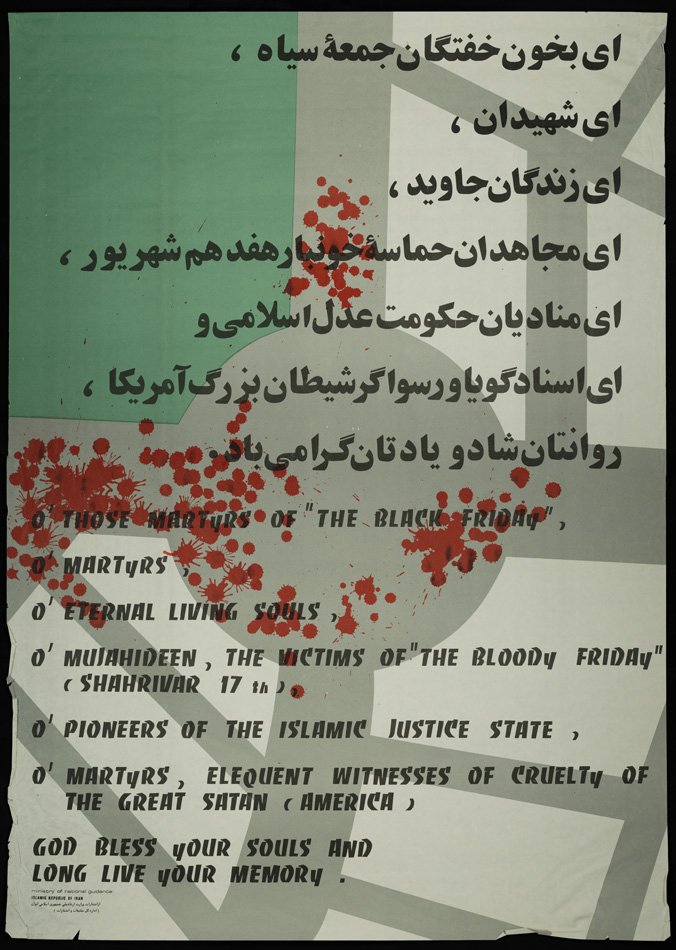

Only a few weeks after this catastrophic event, the tide turned definitively against the government when, on September 8, 1978, government tanks and helicopters opened fire against thousands of protesters in Tehran, killing dozens. Known as Black Friday, the event was consecrated in revolutionary posters that depicted the bloody aftermath in the streets of Tehran while claiming the deceased as victims, martyrs, and pioneers of a just Islamic state (fig. 1). Black Friday was the pivotal event during the revolution and marked the beginning of the end of the Shah’s rule.

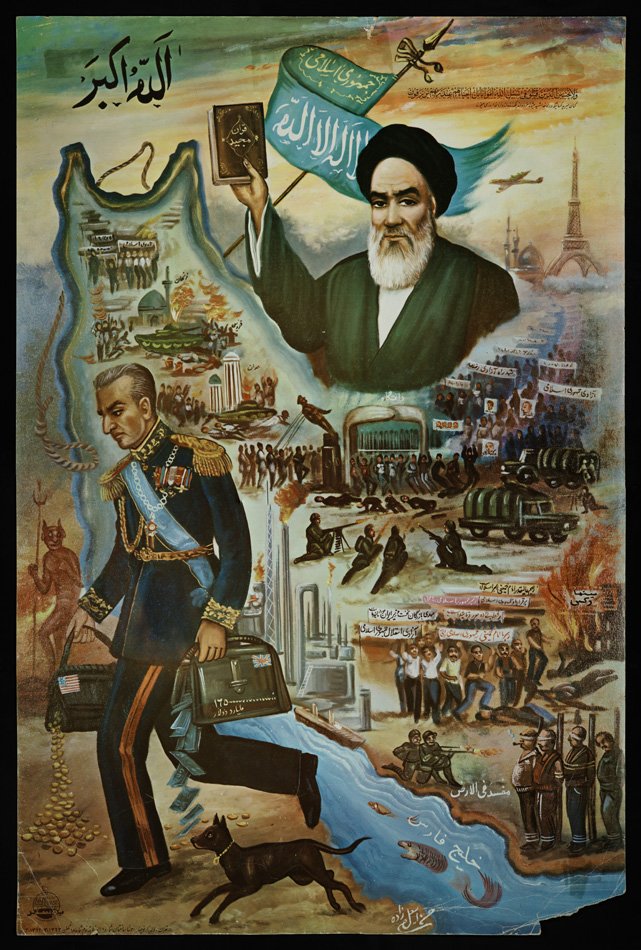

On January 16, 1979, Mohammad Reza Shah fled Iran, and on February 1, Khomeini returned from his exile in Iraq and Paris to be greeted by millions of cheering Iranians. Emerging as the clear leader within a power vacuum, Khomeini and his supporters worked quickly to consolidate power. Results from a referendum the next month declared the formal dissolution of the monarchy and the formation of the Islamic Republic of Iran. These swift changes were immediately celebrated in posters and other graphic media, as Iran’s printing presses were no longer controlled by the Pahlavi regime (fig. 2).

During the climactic period of civil unrest lasting from October 1977 to January 1979, protesters produced posters and pasted them on graffiti-scribbled walls. The resultant display of public dissent echoed the violence in the streets of revolutionary Iran. Several artists chose to recreate the chaotic urban landscape in their posters, which thus record the anti-imperial slogans and chants that were scribbled on walls, while also praising the chief ideologues of the revolution, including Ayatollah Khomeini and Ali Shariati (fig. 3).

Posters produced by the Islamic regime after 1979 reimagined the revolution as an ideologically Islamic one, even though it was a pluralistic uprising composed of both secular and religious groups.1 Shi‘ite Muslim rituals and symbolism, however, were key in sustaining revolutionary fervor. As a result, the artistic program of the newly formed Islamic Republic emphasized the Shi’ite aspects of the protests above all others in order to legitimize the newly formed government’s claims to spiritual authority and supremacy.

Demonizing the Enemy

Another driving force during the revolutionary period was the demonization of both real and perceived enemies. The Pahlavi monarch was the main target of antagonistic protest chants, graffiti slogans, and leaflets distributed during the revolution. After the U.S. Embassy was stormed by a group of young Islamist radicals on November 4, 1979, however, attention also turned towards the United States (nicknamed “the Great Satan” in Iran). Together with the United Kingdom, the U.S. was seen as the real power behind the Pahlavi monarchy and was still resented by Iranians for the 1953 CIA-led coup d’état that overthrew the democratically elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq.

The U.S. was characterized in Khomeini’s speeches and the Islamic Republic’s propaganda as a decadent and corrupt imperialist nation. By depicting the U.S. as the moral antithesis of the Islamic Republic, Khomeini and his supporters aimed to capitalize on the Iranians’ approval of the U.S. hostage crisis, while simultaneously galvanizing the populace to identify with the Islamic Republic and its mission.

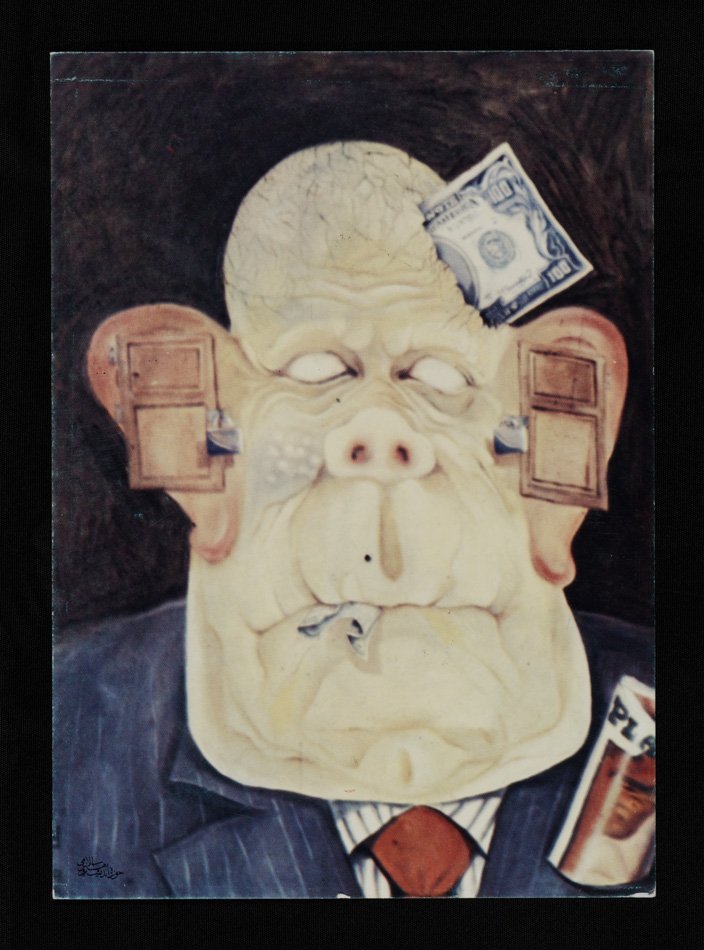

Images produced at the height of anti-U.S. sentiment include, for example, postcards of a corrupt and grotesque President Carter, with ears locked shut and money shoved into his head and mouth. Such images served to vilify the American government and to underscore the moral decadence of capitalism (fig. 4).

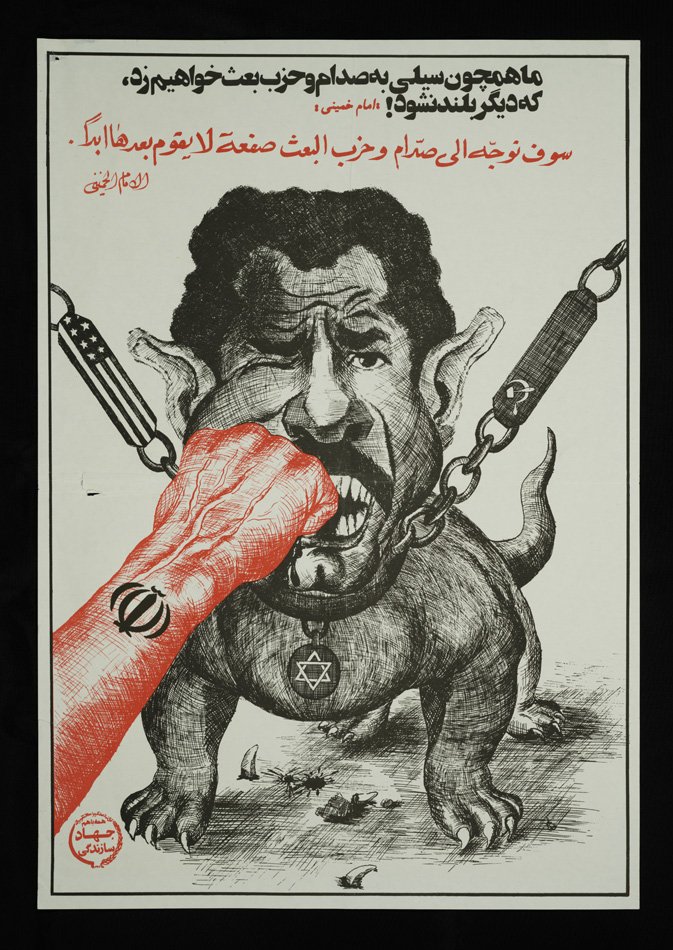

The other recipient of post-revolutionary animosity was Saddam Hussein. Khomeini hoped to inspire other Islamic revolutions across the Middle East, including in Iraq, where Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime ruled over the largely Shi’a population of Iraq with an iron fist. One poster of Saddam Hussein produced in Iran around 1980 shows him as a growling bulldog leashed in by the Soviet Union, the U.S., and Israel, to be defeated by the collective punch of the Iranian people’s striking fist (fig. 5). By depicting Saddam as merely an attack dog of foreign world powers, the poster insults him and diminishes the danger posed by the Iraqi leadership, while predicting its eventual destruction by the Islamic Republic.

In September 1980, Saddam Hussein, feeling threatened by the Islamic Republic’s attempts to incite the Iraqi Shi‘a majority to overthrow his leadership and seeking to take advantage of the revolutionary chaos in Iran, ordered the invasion of Iran. Thus began the eight-year Iran-Iraq War.

A New Battle of Karbala

Marked by chemical weapons and human-wave assaults, the Iran-Iraq War was one of the deadliest wars of the twentieth century. Facing the existential threat of the Iraqi invasion, the struggling and militarily weak Islamic Republic deployed an immense propaganda campaign in order to convince Iranians to fight on the war front. Young men enlisted in the army and paramilitary forces, resulting in an estimated million casualties on the Iranian side alone. The war was devastating, and hence it needed to be given greater symbolic meaning.

At this time, fighting for the Islamic Republic was conceived as a righteous reenactment of the Battle of Karbala. In 680 CE the Battle of Karbala resulted in the definitive sectarian split between Sunni and Shi’a Islam. In the wake of the succession crisis following the death of the Prophet Muhammad, the Umayyad ruler Yazid I sought to assassinate Husayn, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. Accompanied by his family and followers, Husayn fought Yazid on the plain of Karbala, where he was brutally murdered. For the Shi’ite community, Husayn’s death stands as the seminal act of martyrdom and the promise of salvation. As a prototype for self-sacrifice, Imam Husayn was the model to which Iranians aspired in their own modern-day Battle of Karbala.

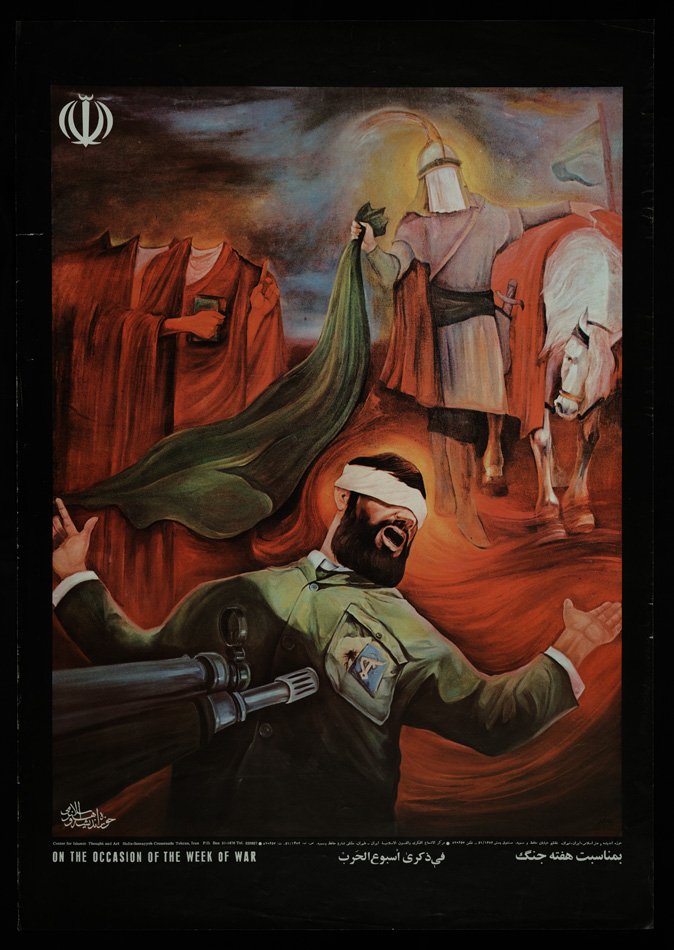

Posters and other graphic media conflated the historical past with the present, as soldiers were repeatedly depicted as martyrs on the battlefield of Karbala. For instance, one poster entitled The Martyr depicts a blindfolded Iranian soldier being executed and thrust from this world into the next, where Imam Husayn and decapitated martyrs await him (fig. 6). The Islamic Republic thus successfully tapped into a larger Shi’a framework of salvation by verbally and visually presenting the Iran-Iraq War as a consecrated extension of the Battle of Karbala.2

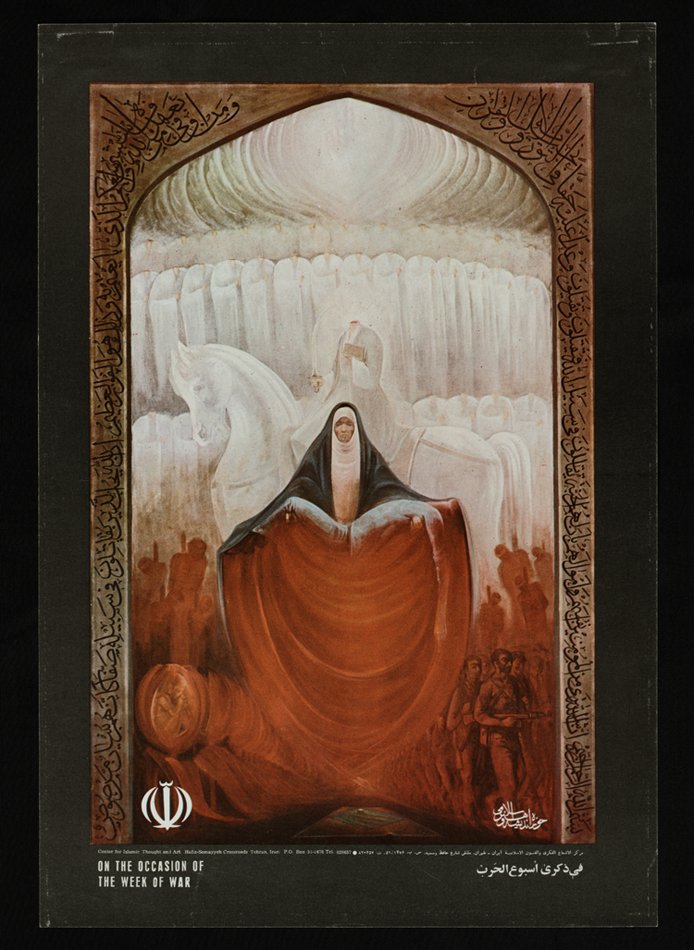

Belief in the salvific reward of a martyrial death is deeply entrenched in Shi’ite culture, and Khomeini employed this religious worldview as a means of urging all Iranian men to fight—and die—for both their religion and their nation. The pictorial arts visualized and consecrated official rhetoric by providing images of the heavenly consummation of martyrs as they are venerated for their sacrifice on earth. The poster Certitude of Belief metaphorically depicts the threshold between a soldier’s death on the battlefield and a redemptive Shi‘a paradise (fig. 7). By encouraging Iranian citizens to die for their country, and by promising individuals spiritual salvation through martyrdom, the Islamic Republic successfully secured its own survival during the war years.

Women and Children

As the fighting raged on, all of Iranian society was urged to take part in the war effort. Posters played a vital role in mobilizing and consoling the Iranian people, including women and children. Iranian boys as young as twelve were recruited to join the Basij, volunteer paramilitary forces that fought alongside the national army. The Basij are most remembered for their human-wave assaults, in which young boys walked across the mine-ridden battlefields to clear them for military maneuvering. Within this deadly act of independence, defiance, and salvific frenzy was the very real desire of young Iranians to protect their homeland and families by any means necessary— including the sacrifice of both limbs and lives.

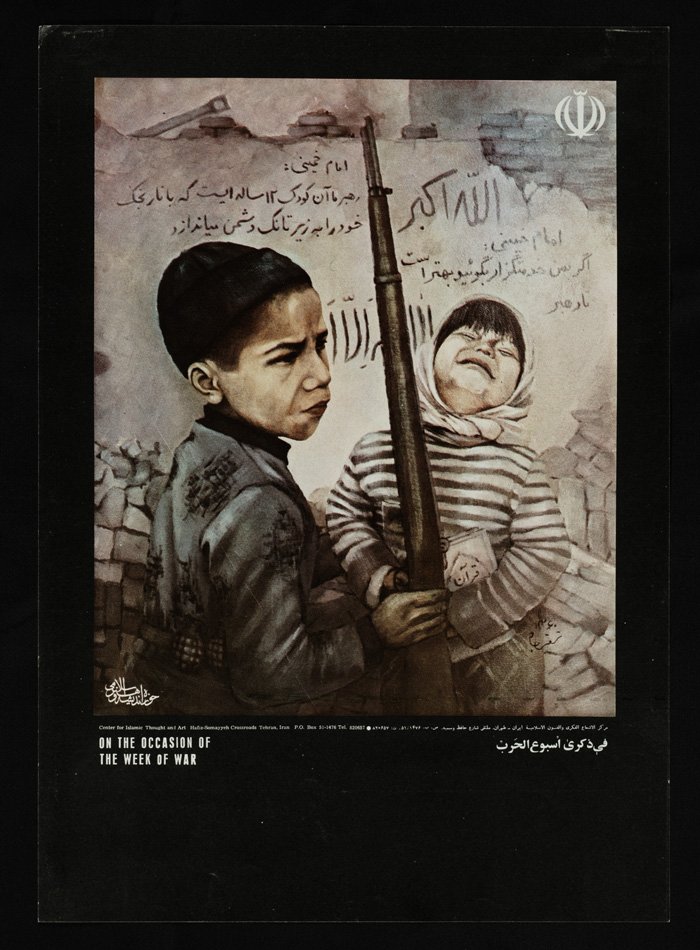

Artists commemorated the bravery of children in the war while also lamenting their tragic and untimely deaths. For instance, one poster, These Are Our Heroes, depicts a young boy preparing to join the battle; the grenades attached to his waist signal his eventual self- destruction in a human-wave assault, as his crying sister clutches the Qur’an (fig. 8). Graffiti writing on the wall behind the two figures exalts other boys as “leaders” who have already sacrificed themselves for the cause. The poster symbolizes a loss of innocence for the young generation, as well as for the nascent Islamic Republic itself.

Women also were targets of wartime propaganda. The Islamic Republic encouraged women to follow Islamic models of femininity and humility. One archetype of Shi‘a female virtue is Fatimah, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad. Venerated as a symbol of righteousness, patience, piety, and as the mother of the foremost Shi‘a martyr, Imam Husayn, Fatimah is exalted as a mother to all martyrs. For these reasons, cemeteries created for Iranian soldiers killed during the Iran-Iraq War are named in her honor.

Another woman exalted by the Islamic Republic is Zaynab, the granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammad and sister of Imam Husayn. She is remembered as courageous and resilient due to her legendary defiance of Yazid I after the massacre of her family at the Battle of Karbala. As an active and even combative female, her example inspired Iranian women during the Revolution. During the war, too, the Islamic Republic’s artistic programs broadcast the image of Zaynab as a woman in support of Shi’a male soldiers.

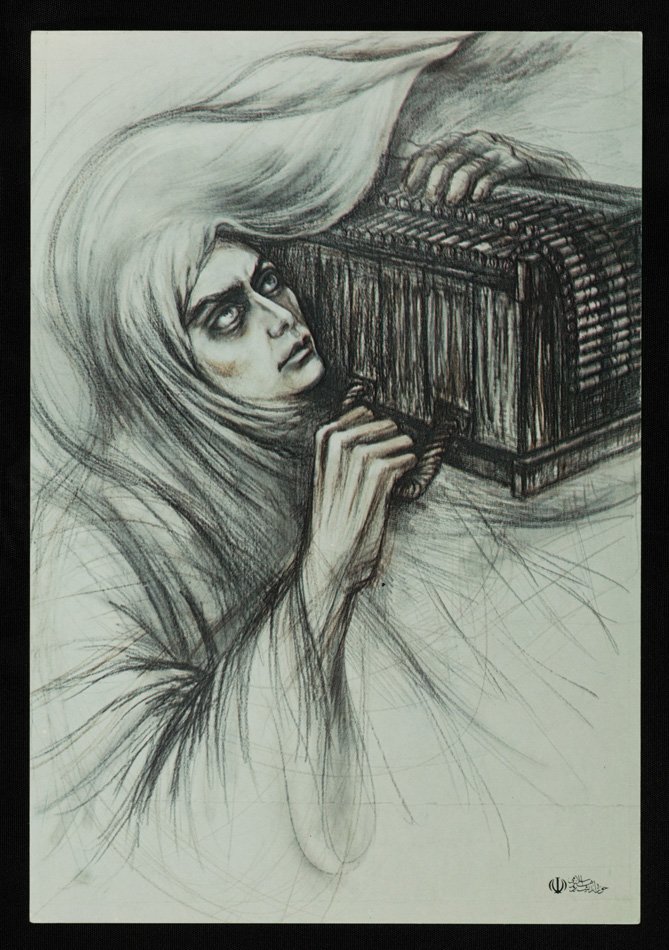

Warfront artist Nasser Palangi produced sketches of Iranian women during the early Iraqi invasion of the Iranian city of Khorramshahr. Titling one of his drawings The Heirs of Zaynab, Palangi makes clear the connection between the seventh-century heroine and the women of Khorramshahr, who fought in defense of the Iranian city (fig. 9). The Battle of Karbala was once again turned into a living paradigm through which female combatants likewise could emulate the heroes of Shi’ite sacred history.

A Graphic Reminder

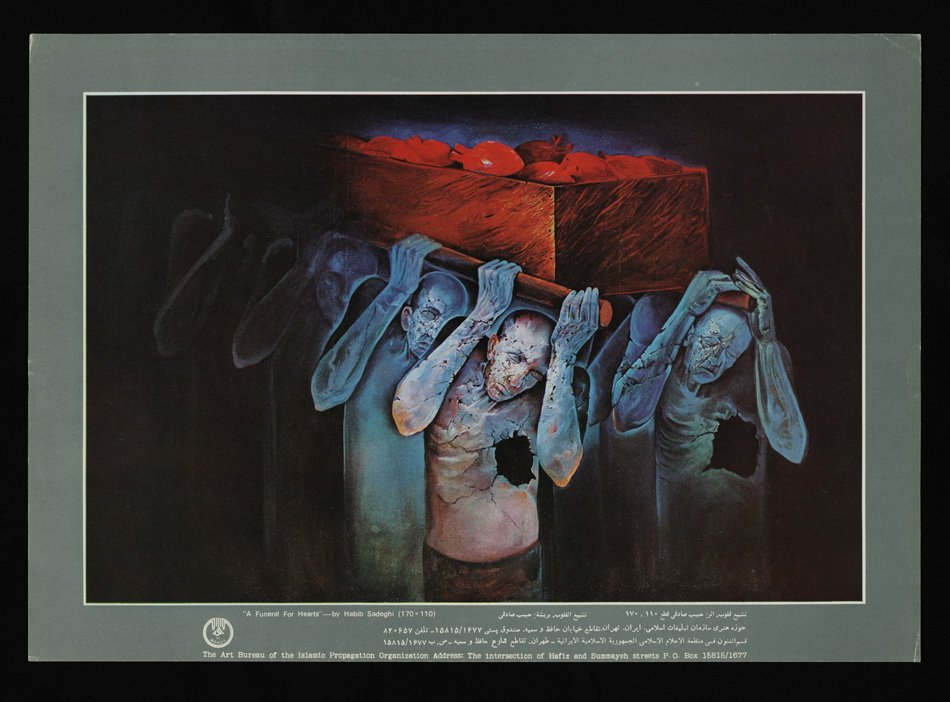

The 1979 Iranian Revolution and the ensuing Iran- Iraq War produced an enormous amount of visual material, much of which still remains unexamined. Works produced during this period—which forever altered the balance of power, both regionally and globally—provide a glimpse into these indelible events and their impact on Iranians and recent history. Visual materials were an important tool of dissemination for a largely illiterate audience, and today they stand as a collective graphic memory of those traumatic years. One such graphic caveat, the highly evocative A Funeral for Hearts, survives as a visual reminder of the physical and emotional pain Iranians endured for over a decade, as a group of dying men carry their own hearts to the grave (fig. 10).

Visualizing these experiences of human trauma and suffering allows individuals to collectively remember, mourn, and safeguard their experiences within a shared historical memory. Iranian posters thus historicized events as they unfolded by commemorating the recent past, preserving the ever-changing present, and charting the unknown future.

Elizabeth Rauh

Ph.D. student

History of Art

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

erauh@umich.edu

NOTES

- For these reasons, Hamid Dabashi and Peter Chelkowski refer to it as an “Islamized,” rather than an “Islamic,” revolution in their Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 22–28.

- On this theme, see Christiane Gruber, “Media/ting Conflict: Iranian Posters from the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88),” in Crossing Cultures: Conflict, Migration, Con-vergence, Proceedings of the 32nd Congress of the International Committee of the History of Art, ed. Jaynie Anderson (Melbourne: Melbourne University, 2009), 685.