Translating Homer

Vernacular translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey began to appear across Europe during the sixteenth century (Modern Greek, French, German, Spanish, Dutch, and Italian from the 1520s to the 1570s; English, 1581), often accompanied by vigorous debates about the theory and practice of translation. Knowledge of Greek and the intended audience shape a translator's approach, and each translation is the product of a distinctive historical, philological, or literary perspective on what it means to translate a work from ancient times that was composed for oral performance.

Translators into English verse have an additional challenge: the archaic Greek meter (dactylic hexameter, or lines of six feet, each foot is made up of three syllables, usually one long and two short), requires paraphrasing or inventing words, or filling out lines, to make the meter conform. English translators have used every possible poetic form, including blank verse, rhyming heroic couplets, Spenserian stanzas, iambic pentameter, and ballad meter. George Chapman, who produced the first translations of Homer into English verse and was determined to present him as a poet, used "rhyming fourteeners" that required substantial paraphrase. Prose translations avoid this problem but give the reader no sense of oral poetry. Madame Anne Dacier turned to prose for her translations from Greek into French because she felt fidelity was impossible to achieve in French verse. John Ozell translated Dacier into English blank verse, the meter of "our English Homer, Milton," which he maintained was best suited to Homeric translation. Johann Heinrich Voss's dactylic hexameter translation was considered the ideal rendition of Homer's language and meaning into modern German.

English translations of Homer have been produced by a wide-ranging group that includes philosophers, prime ministers, clergymen, and a host of schoolteachers, in addition to poets and scholars, some of whose translations have become enduring literary works in their own right. Alexander Pope chose rhyming heroic couplets for his translation, celebrated by his contemporary Samuel Johnson and many others. Classical scholar Richard Bentley, however, remarked, "It is a pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer."

Perhaps the best advice on translation was offered by classicist Donald Carne-Ross to Christopher Logue. Logue recalled in his memoir that Carne-Ross proposed he translate a sequence from the Iliad, but Logue did not read Greek. Carne-Ross advised him to "Read translations by those who did. Follow the story. A translator must know one language well. Preferably his own."

The first lines from English translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey are reproduced in this and other cases so that viewers can experience their vast range and variety.

and William Oldisworth (1680–1734)

The Iliad of Homer. . .

London: Printed by G. James, for Bernard Lintott, 1712.

Sing, Goddess, the Resentment of Achilles, the Son

of Peleus ; that accurs'd Resentment, which caus'd so

many Mischiefs to the Greeks

Ozell admired the scholarship and fidelity of Mme. Dacier's Iliadand translated it into blank verse, dismissing rhyming verse as "too Effeminate" for Homer. Pope mocked Ozell's skills as a translator; in retaliation Ozell took out an advertisement calling Pope an "envious wretch." Most likely to save space and therefore paper, Ozell's printer adopted a prose format.

BHL B8

L'Illiade d'Homere. . . .

Paris: Chez Rigaud, 1711.

Translator and classicist Anne Le Fèvre Dacier spent fifteen years translating the Iliad and the Odyssey into French prose, following the original Greek text, the commentary of Eustathius, and René le Bossu's rules of epic translation. She strove to present Greekless readers with a French version of Homer "much less altered than in previous translations, where he was so strangely disfigured as to be no longer recognizable." Her admiration for Homer and her dedication to fidelity were characteristic of those who sided with the Ancients in the Battle of the Ancients and the Moderns, who believed that modern society had surpassed classical models. Her translation of the Iliad revived the quarrel in France and England.

BHL C5

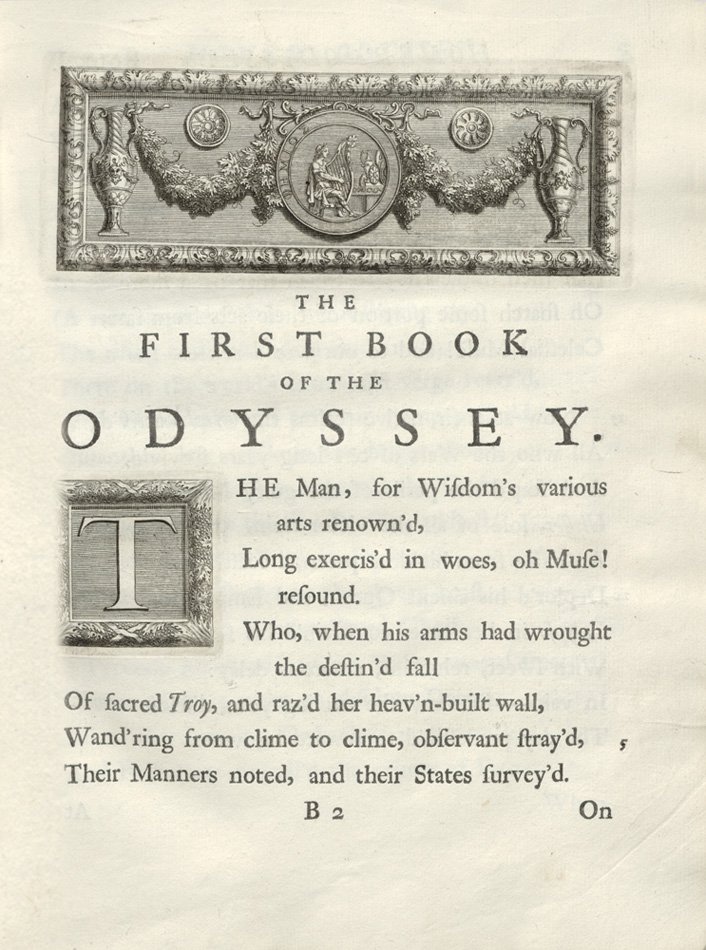

The Odyssey of Homer

London: Printed for Bernard Lintot, 1725-26

THE Man, for Wisdom's various

arts renown'd,

Long exercis'd in woes, oh Muse!

resound.

This is a presentation copy, with Donum Clarissimi Interpretis (Gift of the Most Illustrious Translator) inscribed on the front flyleaf of the first volume. Pope published his translation of theOdyssey by subscription, collecting funds from subscribers in advance of publication as he had done so successfully with hisIliad. He warned readers, however, that "Whoever expects here the same pomp of verse, and the same ornaments of diction, as in the Iliad; he will, and ought to be disappointed." Pope was assisted in this translation by poets Elijah Fenton and William Broomer.

BHL B49

Seaven Bookes of the Iliades of Homere, Prince of Poets. . . .

London: Printed by Iohn Windet, 1598.

Achilles banefull wrath, resound great Goddesse of my verse

That through th'afflicted host of Greece did worlds of woes disperse

This translation of the Iliad books 1-2 and 7-11 in rhyming fourteeners represents not only George Chapman's first attempt at a Homeric rendition, but also the first English translation of a Homeric text. In his preface Chapman explained that he aimed "to give you this Emperor of all wisedome...in your own language." Shakespeare almost certainly relied on Chapman'sIliad for his Troilus and Cressida. This copy has a contemporary parchment manuscript wrapper as a homemade binding. The title page and preface are in facsimile.

BHL B6

The Whole Works of Homer. . .

London: Printed for Nathaniell Butter, [1616].

Achilles banefull wrath resound, O Goddesse, that imposd,

Infinite sorrowes on the Greekes

Playwright, poet, and translator George Chapman published translations of books of the Iliad in several installments before bringing out this first complete translation of Homer's works. Chapman, who relied heavily on Latin translations despite his rejection of their accuracy, declared English the language best suited for Homeric translation. He defended his work against charges of poetic license by describing his work as a "Poeme of the mysteries / Reveal'd in Homer." The unsigned, engraved separate title page for the Odyssey, usually lacking, is present in this copy.

BHL B1

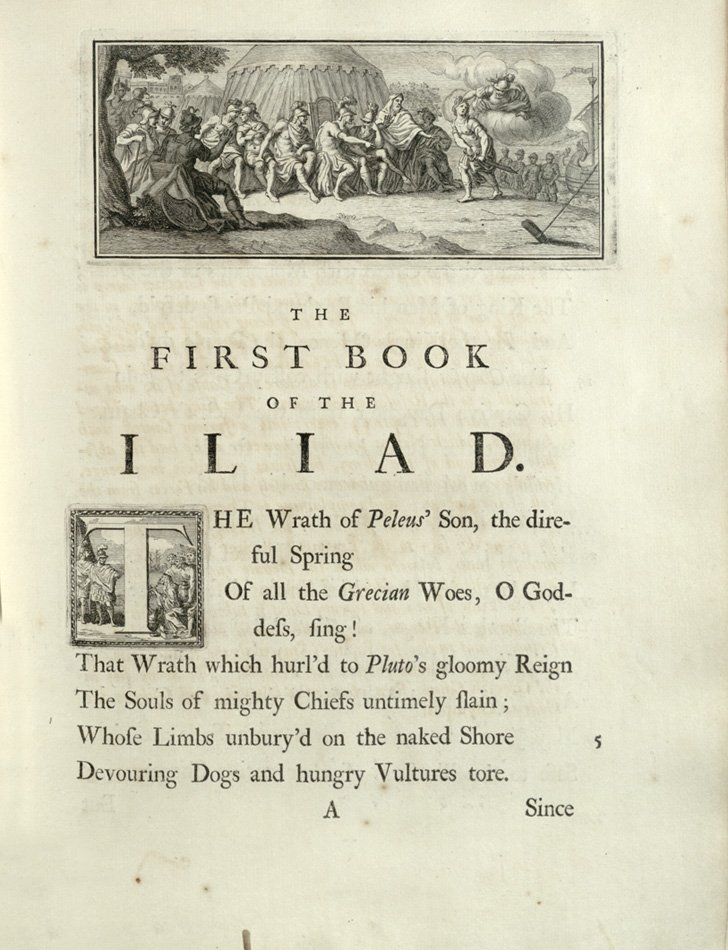

The Iliad of Homer. . . .

London: Printed by W. Bowyer, for Bernard Lintott, 1715–20.

THE Wrath of Peleus' Son, the direful Spring

Of all the Grecian Woes, O Goddess, sing!

This edition of celebrated poet Alexander Pope's translation of theIliad in rhyming heroic couplets was printed exclusively for subscribers. According to Samuel Johnson, only 660 sets were produced, and each volume was sold at a cost of one guinea (a gold coin worth twenty-one shillings or a little more than a pound). Pope received £1200 for the copyright (£200 from the publisher for each of the six volumes) plus all the proceeds from the sale of the subscriber's edition. Pope's total earnings were approximately £5000, a tremendous sum for an author at the time. The quarto format and use of engraved frontispieces as illustrations (rather than merely as formal decorations) were novel and influential. Pope's elevated and elaborate version received immediate and enduring praise: In his introduction to Robert Fagles's 1990 translation, Bernard Knox called Pope's "the finest ever made."

BHL B9

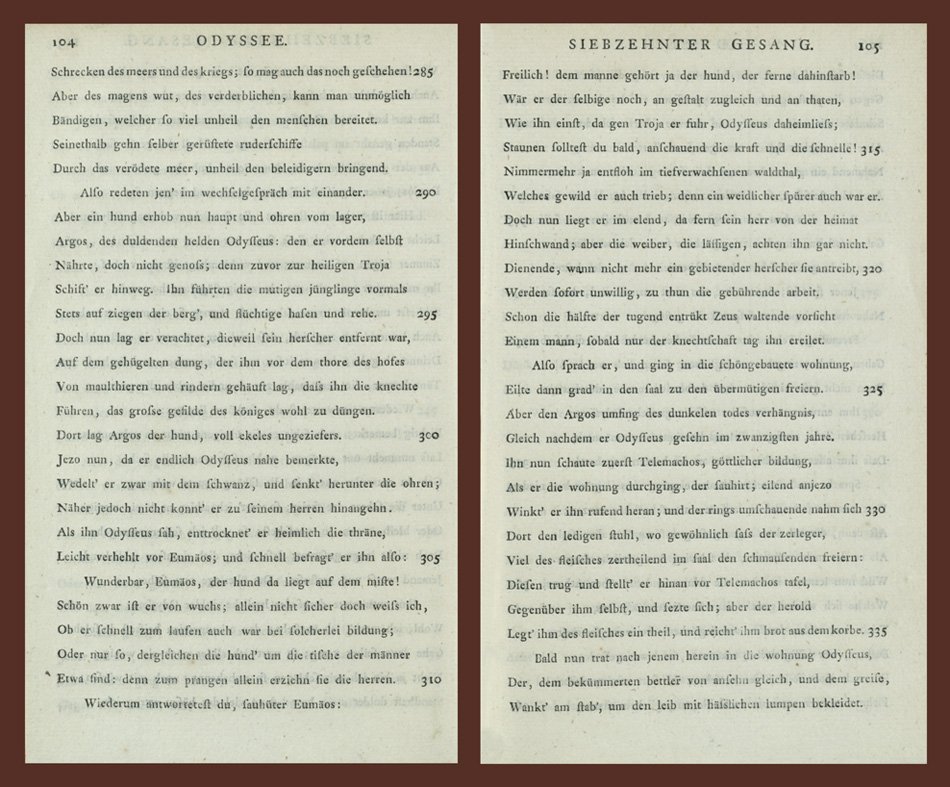

Homers Iliad / Odyssee

Altona: J. F . Hammerich, 1793.

For German readers, Voss's translation made Homer not only a Greek poet, but a German one. This was due partly to his intense study of the poem and of ancient and modern scholarship on it, and even more to his poetic language, elevated but not pompous, direct and only rarely padded. His use of German dactylic hexameters provided the translator flexibility and the long spacious lines gave ample room for polysyllabic epithets in imitation of Homer's.

BHL C13