Early Books on Judaism

Most early books about Judaism were written by Jews who had converted to Christianity and sought both to persuade other Jews to convert and reveal the secrets of Judaism to the Christian world. The illustrations in Johannes Pfefferkorn's Büchlein der Jude Peicht (1508) were revised and reused by Antonius Margartha in his similarly critical Der gantze jüdische Glaube (1530). Although officially discredited and even exiled for his controversial work, Margartha influenced many later writers and shaped Martin Luther's views of Judaism.

During the Renaissance and Reformation, a number of scholars learned Hebrew as part of their biblical studies. For these Christian Hebraists, Jewish beliefs and customs became a matter of scholarly interest. Philologus Hebraeus Mixtus by Johannes Leusden exemplifies the tradition of seventeenth-century Hebraists with its text in Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. First published in 1663, the 1682 edition also shown here includes engravings of Jewish customs by anonymous artists.

Most converts and Hebraists, including Johann Bodenschatz, organized their works around the Jewish calendar or by life-cycle rituals. These works provide insight into the (often hostile) representations of Jews and Judaism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; but they also, through careful reading, yield valuable information about Jewish rituals, clothing, and everyday life in this period.

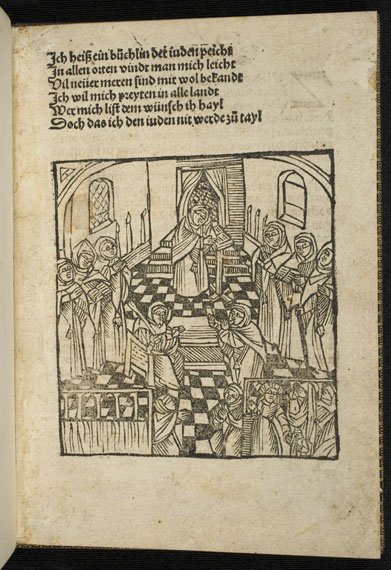

Johannes Pfefferkorn (1469-1522 or 23)

Augsburg: Hannsen Forschauer, 1508

The woodcut illustrations in Pfefferkorn's work are the earliest prints depicting Jewish customs and ceremonies. This scene shows tashlikh, the ceremonial casting away of sins by throwing a piece of bread into a moving body of water, which is traditionally performed on the afternoon of Rosh Hashanah. Additional representations of this ceremony appear in the High Holidays section.

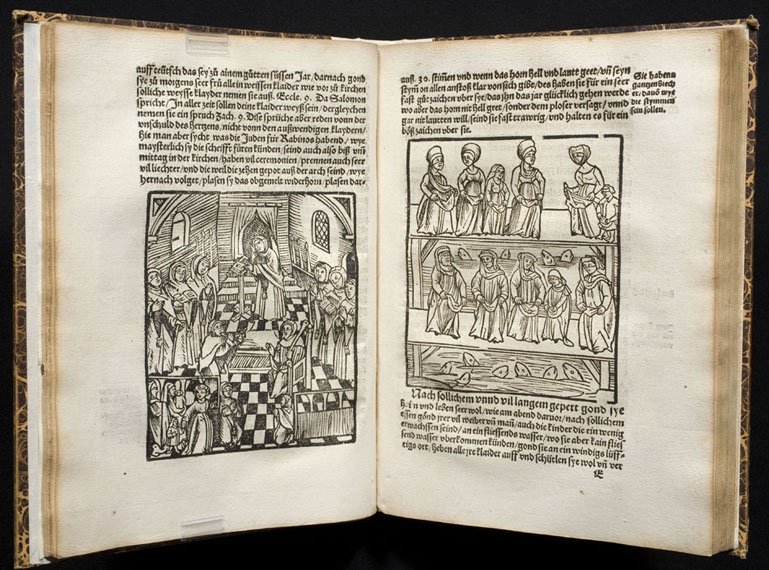

Antonius Margartha

[Augsburg: Heinrich Steyner], 1530

The scene of tashlikh from Pfefferkorn's work above was copied in Margartha's book shown here. Men and women stand on two separate bridges as they cast their bread into the river. The division of the sexes appears in the scene of the synagogue interior on the left-hand page as well. The women and children can be seen in the lower corner, separated from the men by a screen.