Albert A. Michelson (1852-1931): Physics

The founder of the Department of Physics at the University of Chicago, Michelson supervised every detail of laboratory construction, faculty appointments, and equipment specifications. As the years passed, his patience with graduate students wore thin. In 1908, he asked Robert Millikan to supervise thesis preparation, explaining that students were either unable to handle problems as he wanted or "they get good results and at once begin to think the problem is theirs instead of mine."

A master at the art of measurement, Michelson devised experiments noted for their simplicity. Thus measurements of the velocity of light used a rapidly rotating, multifaceted mirror to reflect a beam of light. When the speed was correctly adjusted, light reflected from the rotating mirror struck a mirror held in a fixed position and returned to strike the next face on the spinning mirror. The time needed for the next face to rotate into position to precisely reflect the light was the time required for the light to travel the known distance to the stationary mirror and back. His earliest attempts, made with materials costing barely ten dollars, measured the speed of light at 186,508 miles per second, or within two hundred miles of the actual value.

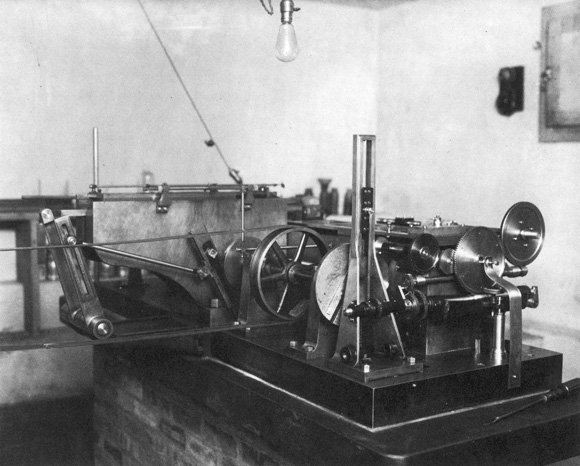

Michelson's ability as a theoretician was matched by his skill as a technician. Michelson was a working scientist, at home with the machinists, the lens polishers, and the "mechanician" who built the machines and instruments he designed. In an age when theory was tested by physical observation of phenomena, he had a dual ability to understand complex problems and then devise and conduct the necessary experiments.

Trained long before Newtonian physics were undermined by Einstein's theory of relativity, Michelson believed that one component of light was the "ether" through which it traveled. His failed attempts to find evidence of its existence had the effect of helping substantiate Einstein's theories. Other advances in physics have long since made Michelson's techniques obsolete, but his serene dedication to pursuing scientific truth and his unwillingness to settle for anything less than precision remain his most telling legacy.

The world of science in which Michelson lived and worked centered on observation, physical measurement, and precision.

Michelson labored for thirty years to perfect his temperamental ruling machine, which he said required "humoring, coaxing, cajoling - and even some threatening!" The machine cut thousands of parallel grooves on small plates of metal. These diffraction gratings were crucial for analyzing light.