Charles O. Whitman (1842-1910): Zoology

Charles O. Whitman maintained a single-minded commitment to original, specialized research. He disdained those who, he said, "flit from point to point, snatching a little here and a little there, learning a little of everything and not much of anything, aiming to amaze the vulgar with glib talk and profuse writing." Whitman's exacting standards and careful attention to detail brought him professional prominence, but they were also a stumbling block. Much of his work remained unpublished. After spending months investigating the eye of an eel, Whitman wrote: "The main feature of this eye has been known to me for two years, but it did not seem best to hasten the communication of the facts before giving the whole subject careful study."

Whitman also believed in open collaboration among scientists regardless of institutional affiliation. He found this goal best served in the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, which he directed for twenty years beginning in 1880. Scientists from various institutions worked side by side, offering one another advice and sharing data and theories. Despite being plagued by inadequate funding, the directors, often at Whitman's urging, rejected financial offers from larger institutions for fear that control of the research program would be lost in the process.

The Marine Biological Laboratory served as a model for Whitman's work in Chicago as head professor of the Department of Zoology. Whitman's students at Chicago and Woods Hole were normally given immediate responsibility for research projects, regardless of their background or understanding. Whitman believed the best students would survive a "sink or swim" test. This approach also had the virtue of relieving him of tedious instructional and supervisory tasks.

Although Whitman disliked departmental administrative details, he seldom delegated authority. His impatience with undergraduates showed most clearly in his formal teaching, for he lectured only one hour per week and kept few, if any, office hours. Even graduate students found him elusive, for he did not always meet scheduled appointments. However, students who sought him out at his home often found him willing and happy to discuss their problems.

Whitman's contribution to the study of biology and zoology came from both his own research and from the influence achieved as the chief organizer of afield of study. Drawing upon his University of Leipzig training, Whitman used German approaches to research and teaching as a standard for his Chicago department. Supporting scientific research was expensive, and Whitman's demands on the University for funds, buildings, and staff were heavy. His arguments were made all the more compelling by reason of his eloquence and high level of commitment; biological research always remained his highest value.

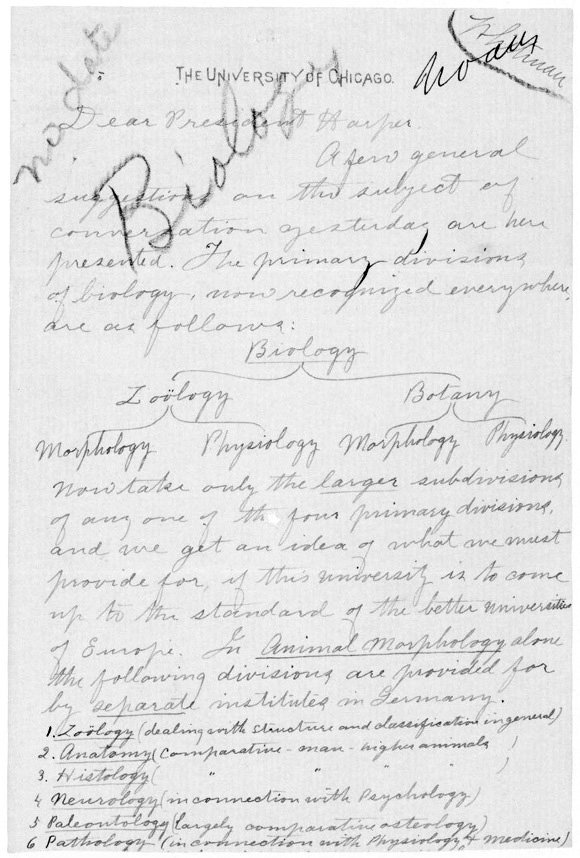

Charles O. Whitman to William R. Harper, undated. Although the University opened with a single, provisional Department of Biology, Whitman intended from the beginning to divide it as soon as possible into a group of departments reflecting the structure of biological research on the German model.

Charles O. Whitman to William R. Harper, manuscript letter, undated

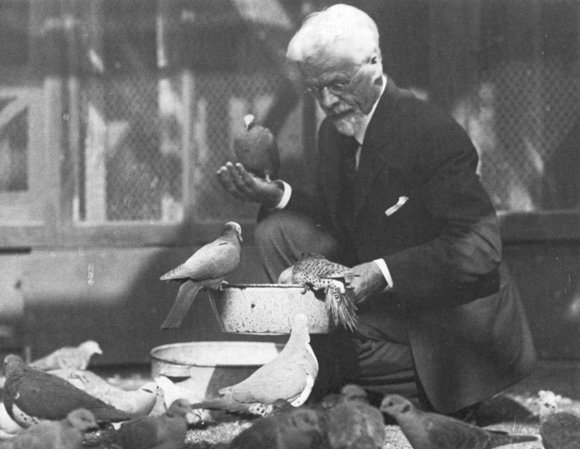

At the end of his career in Zoology, Whitman withdrew from administrative and teaching responsibilities at the University and at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole. Until his death in 1910, he was absorbed in studying evolution and observing the behavior of pigeons he raised near his campus laboratory.