Robert E. Park (1864-1944): Sociology

As an undergraduate at Michigan, Park studied under John Dewey, who introduced him to Franklin Ford. Park and Ford planned a newspaper, The Thought News, as an effort to record public opinion much like a business paper recorded fluctuations in the stock market. The idea never came to fruition, but it clearly anticipated later events. After his sojourn into reporting, Park studied in Heidelberg with Georg Simmel, earning his PhD in 1904.

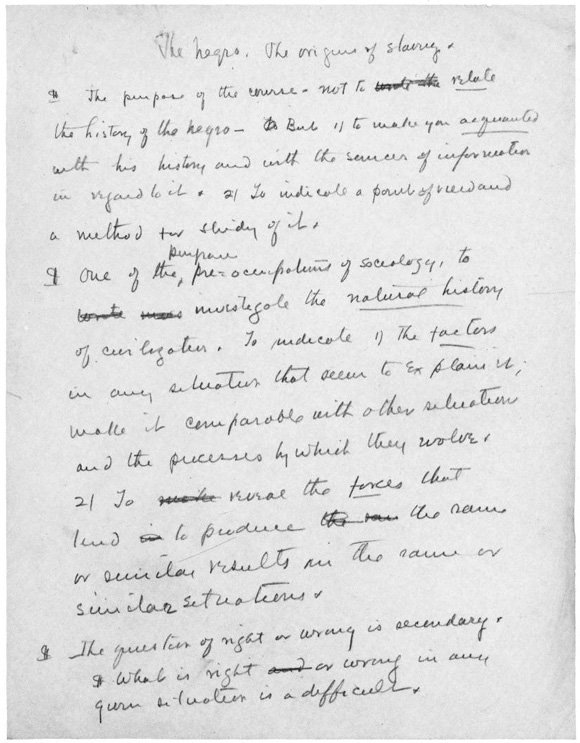

Park's work among Africans and African-Americans, first as a muckraking journalist who exposed King Leopold's exploitation of the people of the Belgian Congo and later as an aide to Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute, remained an important part of his life as a teacher and researcher at Chicago. Park felt he was observing "the historical process by which civilization, not merely here but elsewhere, has evolved, drawing into the circle of its influence an ever widening circle of races and peoples."

Coming to Chicago in 1914 in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Park acquired an ideal laboratory to study the phenomenon of collective behavior and interaction. Chicago, like any great city, was civilization compressed into a small geographical area but with its diversity left intact. Park wrote:

The city is a state of mind, a body of customs and traditions, and of organized attitudes and sentiments that inhere in this tradition. The city is not, in other words, merely a physical mechanism and an artificial construction. It is involved in the vital processes of the people who compose it, it is a product of nature and particularly of human nature.

To Park, individual selfconcepts, goals, and status all contributed to the various forms of society, forms Park believed could be understood in social scientific terms. He was instrumental in drawing sociology away from a normative and often overtly prescriptive analysis of society toward a more objective methodology. This did not, however, lead Park to advocate abandoning earlier efforts to actively intervene and reform society, and he himself participated in such efforts. To avoid the proscriptive approach he criticized in others, he emphasized "the conception of the relativity of the moral order" that was implicit in the work of John Dewey and George Herbert Mead.

The Chicago School of Sociology grew to prominence under Park. Along with Ernest Burgess and Louis Wirth, Park created a theoretical basis for a systematic study of society. His effectiveness as a teacher was demonstrated by the list of notable scholars who studied under him, including E. Franklin Frazier, Charles S. Johnson, Edgar T. Thompson, W. O. Brown, Louis Wirth, Everett C. Hughes, and Helen MacGill Hughes.

Human ecology was a phrase Park coined, borrowing concepts of symbiosis, invasion, succession, dominance, gradients of growth, superordination, and subordination from the science of natural ecology. Such concepts of interaction and dynamic mobility in society were useful in redirecting sociology from reform to scientific analysis without denying the social importance of knowledge.