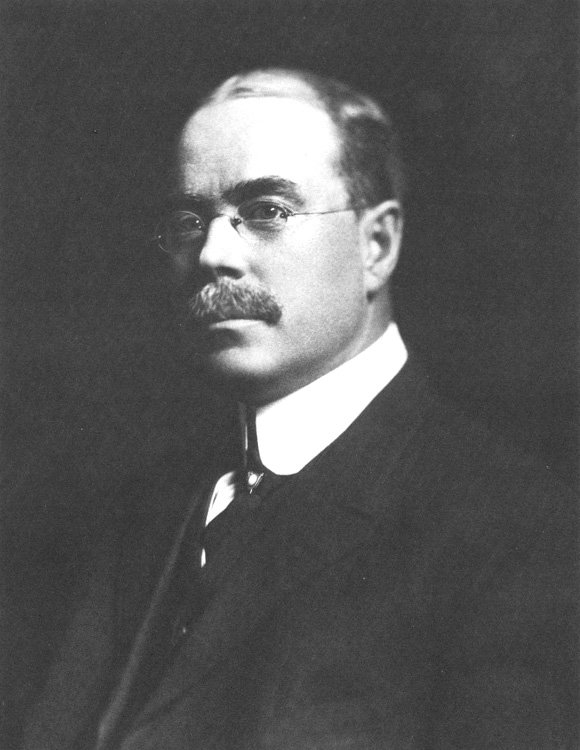

Shailer Mathews (1863-1941): Theology

Not only were Mathews and William Rainey Harper close friends, they shared similar visions of religion and beliefs in the progressive nature of human affairs. Harper brought Mathews to Chicago from Colby College as part of his plan to place religious studies on equal footing with other academic inquiries. Even though the University, in its early years, maintained loose ties to Baptist institutions, the Divinity School operated without denominational constraints.

Theologically, Mathews stood to the left of most orthodox Protestant theologians. When asked if God was a person, he replied, "Conceptually, he is a person; metaphysically we must be agnostic on this." While he was open-minded and tolerant of other views, Mathews drew the line at the ideas of the new fundamentalists. His modernism came under increasing attack during the early twentieth century, not only from fundamentalists but from a resurgence of neoorthodoxy.

Mathews openly embraced the role of scientific inquiry and argued that religion had nothing to fear from advances in science. "We hope to make the technique of religion as intelligible as arithmetic," he once wrote, "to learn what God means to man, man to God. We take nothing for granted." Because he saw religion and science addressing distinctly different questions, he avoided the perplexity afflicting so many when scientific findings contradicted Biblical history. As indicated by the title of one of his books, The Contributions of Science to Religion, he easily incorporated evolutionary theory into his religious views, arguing that the Bible did not exclude evolutionary possibilities.

His belief in higher criticism and the contextual analysis of biblical texts was attacked by literalists who claimed that Mathews had rejected the very essence of the Christian faith. Unintimidated by such controversy, Mathews engaged all comers in a lively and pointed debate over issues of interpretation, doctrine, and implementation of the Gospel. His ultimate concern lay with the present and not the hereafter. In what may have been Bond Chapel's shortest sermon, Mathews said of the afterlife: "What worries me is not if I shall have immortality, but if I have it, what I'll do with it. Shall we pray?"

Mathews believed that social problems could be ameliorated through the application of scientific principles. When fused with Christian ethical standards, the Social Gospel would be a powerful weapon against the ills of modern times.

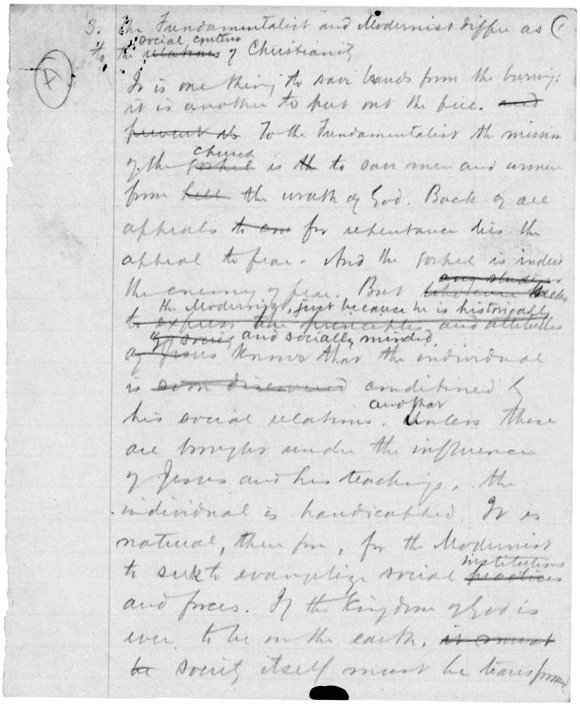

Mathews met the rising tide of fundamentalism head-on. While he clearly understood many of the reasons for its popularity, he was not prepared to yield any of his liberal convictions. "If the Kingdom of God is ever to be on the earth," he wrote in these notes, "society itself must be transformed."