Harold H. Swift and the Swift Family

Few early donors to the University of Chicago gave so consistently and yet so quietly as Harold Swift. An alumnus (Ph.B., 1907) and longtime member and President and Chairman of the Board of Trustees (the latter role from 1922 to 1949), Swift was deeply devoted to "his school," a commitment he demonstrated time and again and often by means of anonymous contributions. His donation of the Swift Prize in Civil Government in 1909 launched what was to become a distinguished career of philanthropy at the University Chicago. Harold Swift was also a family gadfly, mobilizing members of his family on behalf of the University. Swift money, channeled through Harold, subsidized the Library as well as numerous departments, research projects, student prize funds, lectureships, and endowed professorships.

A life-long bachelor, Harold Swift (1885-1962) seemed so consumed by his work that he failed to develop deep social relationships beyond his family. Rather, he dedicated his life to the University, manifesting, according to historian Dorothy V. Jones, a powerful sense of proprietorship toward the institution. A businessman willingly swallowed up within a community of articulate and opinionated scholars, he occasionally seemed like a fish out of water. But Swift valiantly defended "his" community against its enemies, seen and unseen. When various forces in the 1930s sought to characterize the University of Chicago as a hotbed of radicalism, he responded briskly with countervailing evidence. As Chairman of the Board, he had the responsibility, he believed, to "understand and interpret the institution to the public."

A large share of Swift's personal donations (along with thousands of his books) went to strengthen the Library, though he occasionally directed funds elsewhere. The "best expenditure of funds" for educational purposes, he declared, "is to make the best places better." Thus, he established the William Vaughn Moody Lectures in 1917 with a pledge of $1,500 a year for five years to bring eminent scholars to campus. He also provided part of the funds needed to acquire the Morton Collection of Drama in 1928, a comprehensive collection of published and unpublished play scripts.

One of Swift's most effective contributions was the $5,000 he gave to help poet and editor Harriet Monroe continue the publication of Poetry magazine. In return, Monroe agreed to bequeath her personal papers and editorial files to the University (along with the residue of the $5,000 gift). Monroe's Poetry manuscript files, received by the Library in 1936, and the funds to continue acquiring contemporary poetry, became the core of the University's impressive holdings in modern poetry and literature. Swift also supported the work of the Department of Music and the University Opera Association, and he gave a large donation in 1920s to an alumni committee organized to buy manuscripts for the Library. He even gave animals raised on his Michigan summer estate property to the Department of Medicine for scientific research.

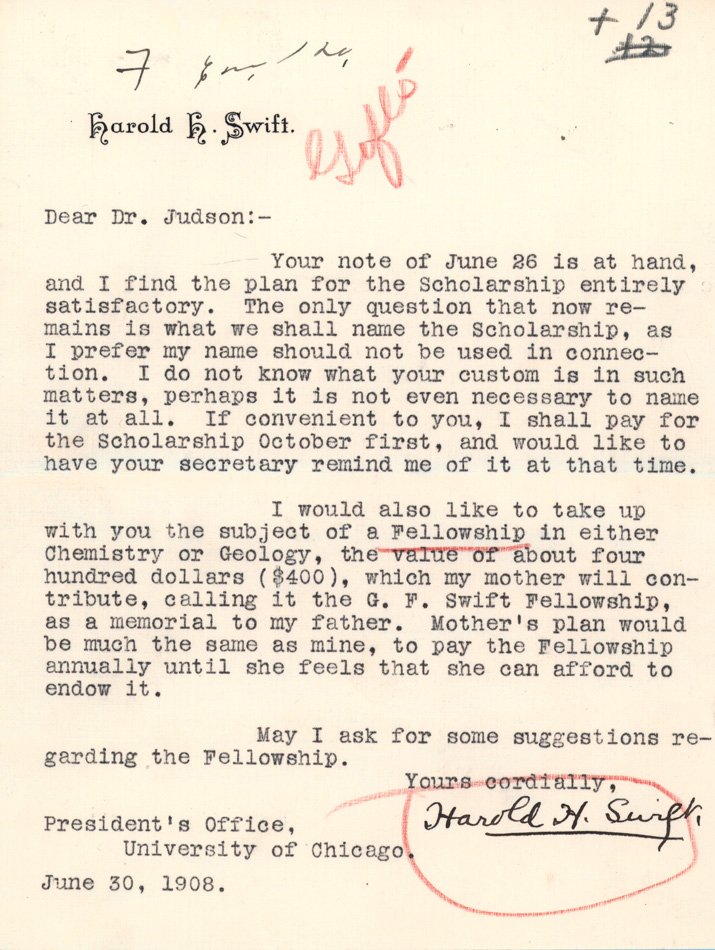

Nor was Swift's generosity limited to his own gifts. He also encouraged the members of his family to support the University. The Swifts dominated giving in the 1920s, favoring especially the kinds of programmatic donations that the development campaign of 1924-26 encouraged. Harold's older brother Charles, along with his mother Ann, contributed heavily to building and research funds. After establishing the Gustavus F. Swift Fellowship in Chemistry in 1908, Ann Swift quickly eclipsed this initial donation with an array of contributions to medical research (a total of $100,000 to match the $200,000 Harold and Charles gave jointly), other research endowments, and the construction of Swift Hall as the new home for the Divinity School (completed in 1926). Charles continued his mother's example by establishing one of President Burton's new endowed professorships, the Charles H. Swift Distinguished Service Professorship, in 1926. He also donated to a variety of other campus causes, including faculty travel grants and departmental research funds. In1929, with an initial transfer of Swift and Company stock worth $50,500, Charles created the nucleus of a special fund to which he added regular increments of $15,000 or more amounting to a total of $130,000 within the following two years. Dedicated initially to endowing the Distinguished Professorship named in his honor, the Charles H. Swift fund continued to grow with additional gifts in the years that followed and still serves as a major support for undergraduate education.

Harold also encouraged sisters Ruth Swift Maguire and Helen Swift-Neilson to donate to the University. Ruth's discretionary fund bought the University's first cyclotron, funded Arther Compton's cosmic ray research, established the school's Institute of Statistics, and funded publication of the second volume of the Dictionary of American English. She also gave toward the purchase of John M. Manly's personal library and helped the University acquire the Grant Collection of English Bibles in the 1940's.

The gifts of Helen Swift Neilson and Charles Swift transformed the Library's American literature holdings into notionally renowned collections, especially in the filed of drama. In 1917, Percy Boynton set out to establish a program of courses and encourage graduate students to pursue research in this field. To accomplish his goal library resources were needed, and these — readily available at Eastern institutions — were sorely lacking at Chicago. With the support of John Manly and President Judson, Boynton explained the situation to Harold Swift and his sister, Helen Swift-Neilson (then Mrs. Edward Morris). Beginning with an initial gift and continuing by creating an endowed fund, Mrs. Neilson established what was later designated the William Vaughn Moody collection after the prominent author and University faculty member. By the early 1940s the collection numbered approximately 15,000 volumes and included works by famous and obscure authors, many in first and early editions.

In 1925 Charles Swift supported the acquisition of a literature collection formed by F. W. Atkinson of Brooklyn. The collection included several thousand early American plays and was considered stronger in this area than Harvard's, then the most comprehensive. A group of 73 early American novels was purchased from Atkinson with support from Mrs. Neilson in 1931; and during the 1930s, Charles Swift supported the purchase of additional theatrical resources and a large collection of motion picture "stills."

By the time of Harold's death in 1965 he could look back with great pride on his family's extraordinary philanthropy in support of Chicago. Harold Swift was a worthy successor to those heroic early donors, like Rockefeller, Ryerson, and Hutchinson, who had the determination and courage to launch the new University.

In response to information on this page, Jonathan Wegner, UChicago PhD candidate, presented a talk entitled "Life of the Mind Talk: Swift 101", available here in UChicago's Knowledge Repository.

Abstract: This talk discusses the unsavory aspects of the legacy of Harold H. Swift which have been officially ignored by the University of Chicago and beyond. I show that he was a key figure responsible for the making of Swift Hall where the Divinity School is housed, and, to a lesser extent, other unique dimensions of the University of Chicago. During his lengthy tenure as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the University of Chicago (1922-1949), he remained a powerful donor who supplied the essential funds responsible for Swift Hall's material construction and exercised rare administrative oversight over the process. Under his consequential chairmanship in the 30s and 40s, the University of Chicago saw its nadir in local race relations. Swift successfully instructed the administration of the University to legally support, fund, and help organize powerful efforts to bar and evict local non-whites, especially African Americans, from living near campus.

The author provided this biographical/background statement: "Hello, readers! My name is Jonathan Darnell Wegner, my family and I are from the West Side of Chicago, East Garfield Park above all. I am a member of the Faith Community of St. Sabina in Auburn Gresham, and a doctoral candidate at the Divinity School at the University of Chicago. I am currently completing my dissertation detailing the cultural linkage between the ancient Egyptian apocalypse Poimandres (Ποιμάνδρης) and the Gospel according to John (Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην). I gave the talk on Harold H. Swift in 2021 as an act of civic discipleship on campus for the sake of humanistic uplift, which for me existentially stems from having to endure the daily maintenance of imperial narratives determined to erase the memory, experience, and voice of my community and adjacent peoples. A special shout-out to the brave, righteous sister Miriam Attia, especially for her role in providing space for the talk. And special thanks to Doctor and Bibliographer Anne Knafl, who also contributed to the preparation of my lecture. May it overturn powerful and entrenched agendas aimed at controlling the meaning and possibilities of history, and thereby awaken those present to new life!"