Helen Culver

The turn of the twentieth century was a time of significant expansion and change in scientific research. Great strides were being made in the campaign to discover the causes of disease. Beginning in 1901, a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded annually to honor the world's leading scientists for biological research, including studies of widespread diseases such as diphtheria, malaria, lupus, and tuberculosis. Many scientific researchers were pursuing valuable work at the nation's institutions of higher learning, including the University of Chicago. But the new University's ambition was constrained by its lack of research facilities. By the mid-1890s the University had a number of distinguished scientists of its faculty, but it lacked the facilities to provide them with supportive laboratory environments. To secure its place at the forefront of scientific research in the United States, Chicago desperately needed the resources provided by donors like Helen Culver.

While she was still rather young, Helen Culver (1832-1925) moved from her home in upstate New York to the Illinois prairie in the hopes of establishing herself as a teacher, but quickly gave up a career in education to respond to a plea for help from her cousin Charles J. Hull. Hull's wife had died in 1860, leaving him with two young children in need of a surrogate mother. Constrained by domestic expectations and feelings of familial duty, Helen took on the responsibility of raising the youngsters until their premature deaths in 1866 and 1874. Several years later, Charles Hull also died—leaving his fortune to Helen.

Over the years Helen Culver became a business associate of Hull and was partially responsible for the growth of his real estate empire. She opted not to spend her fortune on herself but rather to give it away to worthy local institutions. She was particularly interested in Jane Addams' social reform work on the city's West Side. Learning that Addams and her colleagues needed a base of operations, she generously gave them the title to the Hull family home on Halsted Street. The reformers gratefully named their institution Hull House and made Culver one of the settlement's trustees. An advocate of efficient government and education, the reform-minded philanthropist also financed an inquiry into municipal revenues and funded University of Chicago professor W. I. Thomas's research with Florian Znaniecki on the life of Polish peasants in Europe and their immigration to America.

Perhaps the greatest example of Culver's philanthropy were her donations totaling $1.1 million to the University of Chicago. Beginning in 1895, she contributed steadily to a fund dedicated to the construction of four scientific research laboratories for zoological, botanical, anatomical, and physiological investigation. Known as the Hull Biological Laboratories, the buildings were finished in 1897 and were a symbol of Culver's personal interest in advancing research and teaching in the natural sciences. In comments at the buildings' dedicatory ceremonies, she expressed her desire to support "those forms of inquiry which explore the Creator's will as expressed in the laws of life" and to be the "means of making lives more sound and wholesome."

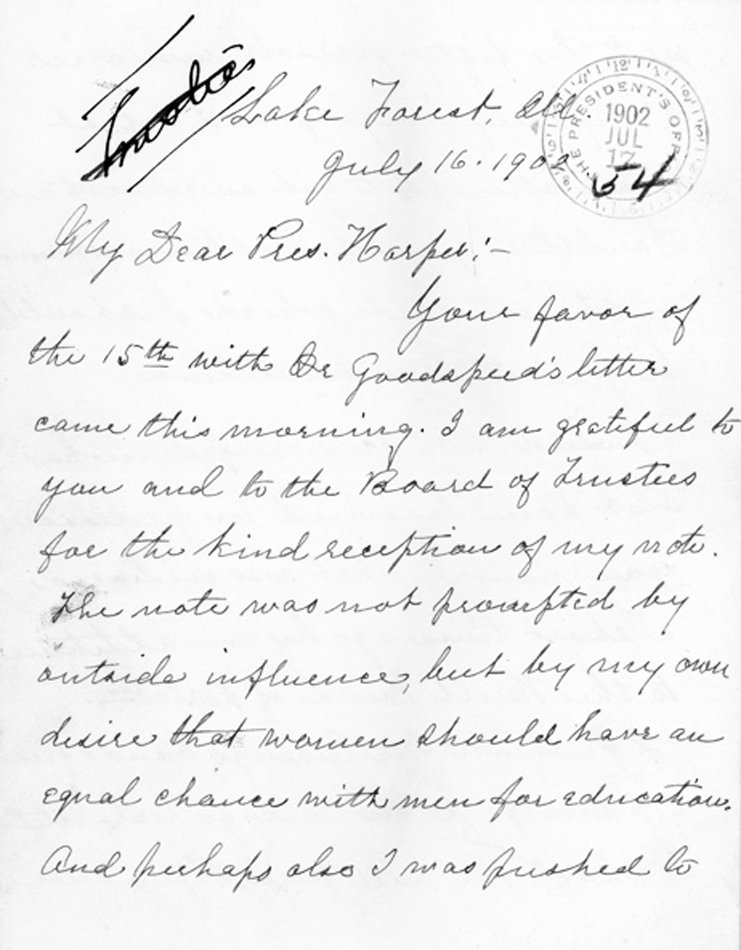

The Hull Court buildings did not end Culver's relationship with the University of Chicago. When reports began to circulate that the University administration was considering plans to segregate male and female students, she wrote a strongly worded letter to President William Rainey Harper in July 1902. She was prompted, she said, not "by outside influence, but by my own desire that women should have an equal chance with men for education." Gender segregation of any kind at the University of Chicago, Helen Culver believed, was absolutely unwarranted. While the University began to implement segregation for the first two years of undergraduate education, faculty and alumnae opposition to the plan was immediate and overwhelming, and the experiment was soon abandoned. Culver's generosity found final expression in a provision of her will bequeathing $600,000 from her estate to the University of Chicago.