Magic in Humanist Florence

John-Paul Heil

Magic was as prevalent a subject of study in the Renaissance as science is today. In Florence, humanist scholars discussed the relationship between magic and classical theology, philosophy, and the natural sciences, and their treatises often served as practical guides to performing magic. The most prominent Italian scholar of magic was Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), best known for completing the first complete translation of Plato into Latin as well as his Platonic Theology, which wove together Christianity, Platonism, Neoplatonism and Arabic philosophy into a coherent system which aimed to remedy much of the same institutional corruption, hypocrisy and doctrinal inconsistency which Martin Luther would take on a few decades later. Ficino, who called himself a “doctor of the soul,” also outlined cohesive hybrid system of magic, which would inspire a decades-long intellectual obsession with magic throughout Europe. Ficino and other Florentine scholars of magic, despite their high status in a city entranced by humanism and the ancient world, often came under public and official suspicion as practitioners of potentially dangerous arts. Magic itself was not forbidden—many kinds of magic were acceptable parts of daily life—but instead authorities sought to ensure that magic was not being used or taught in ways which might be dangerous, heretical, or impious, especially since Renaissance magic so often intersected with theology. Magic also intersected with natural philosophy, especially with cosmology and medicine, and innovations in theories of magic were often the arena in which the greatest scientific discoveries were made and disseminated in the centuries before the Baconian revolution.

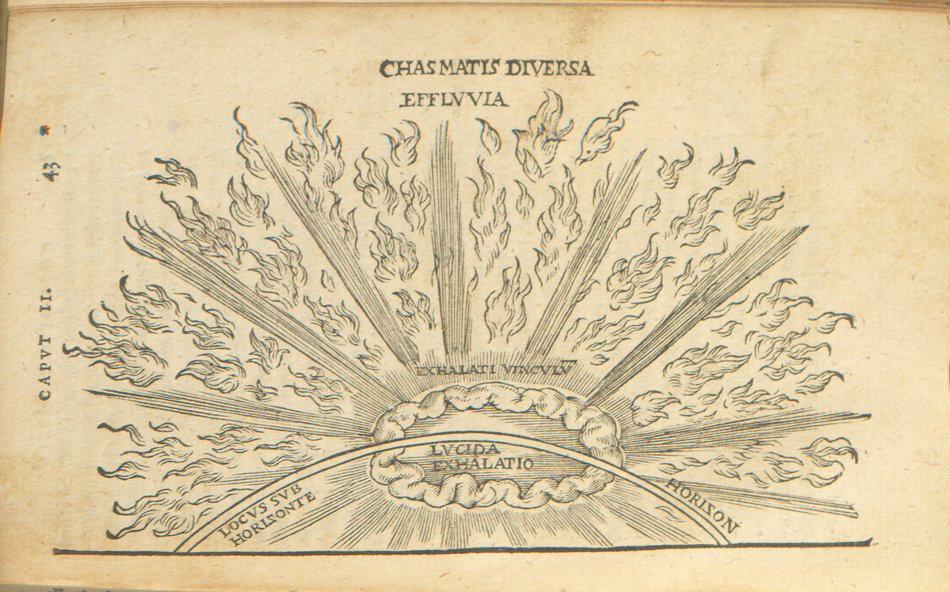

Cornelius Gemma (1535-1579)

Antverpiae: Ex officina Christophori Plantini, 1575

Rare Books Collection

Europe’s fascination with magic and astrology led to increasingly empirical ways of cataloging astronomical phenomena. In his De naturae divinis characterismis, Dutch intellectual Cornelius Gemma became the first to illustrate an aurora while discussing a supernova observed in 1572. The book, which focused on natural sciences, also attempted to incorporate astrology into the field of medicine, demonstrating magic’s status as a serious academic “science” even in the years leading up to the Enlightenment.

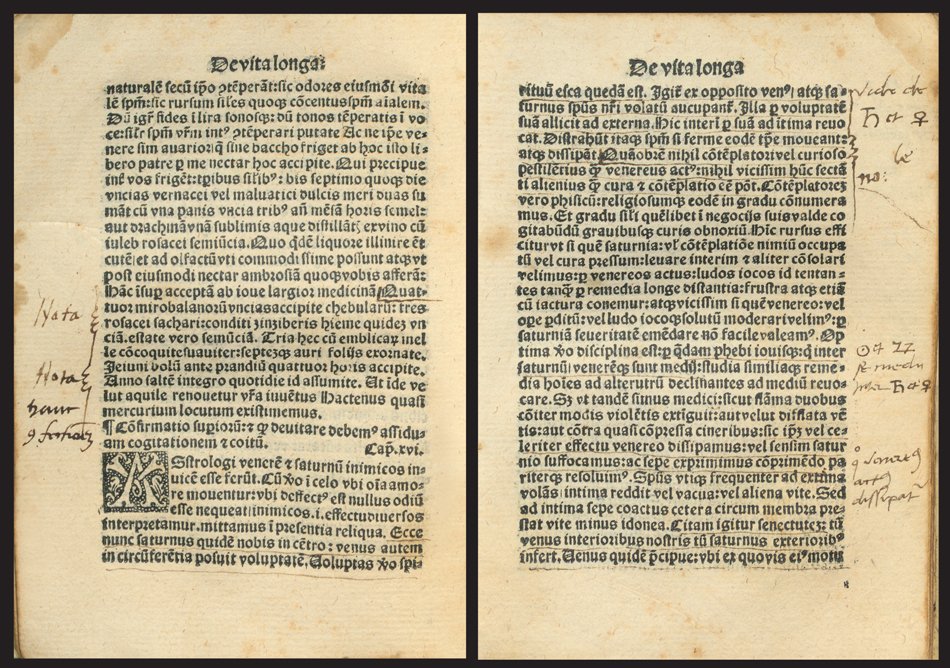

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499)

Parrhysijs: Ab Joanne Paruo, [1515]

John Crerar Collection of Rare Books in the History of Science and Medicine

In the third book of De Triplici Vita, Marsilio Ficino explored the role of magic in philosophy and nature, examining things like the mechanics of the body’s connection with the soul and how to capture the powers of stars in gold or silver rings. Although Ficino himself was fascinated with Neoplatonism, later readers, like the writer of this sixteenth-century marginalia, were more interested in the text’s applicability as a manual for performing magic and conducting astrology.

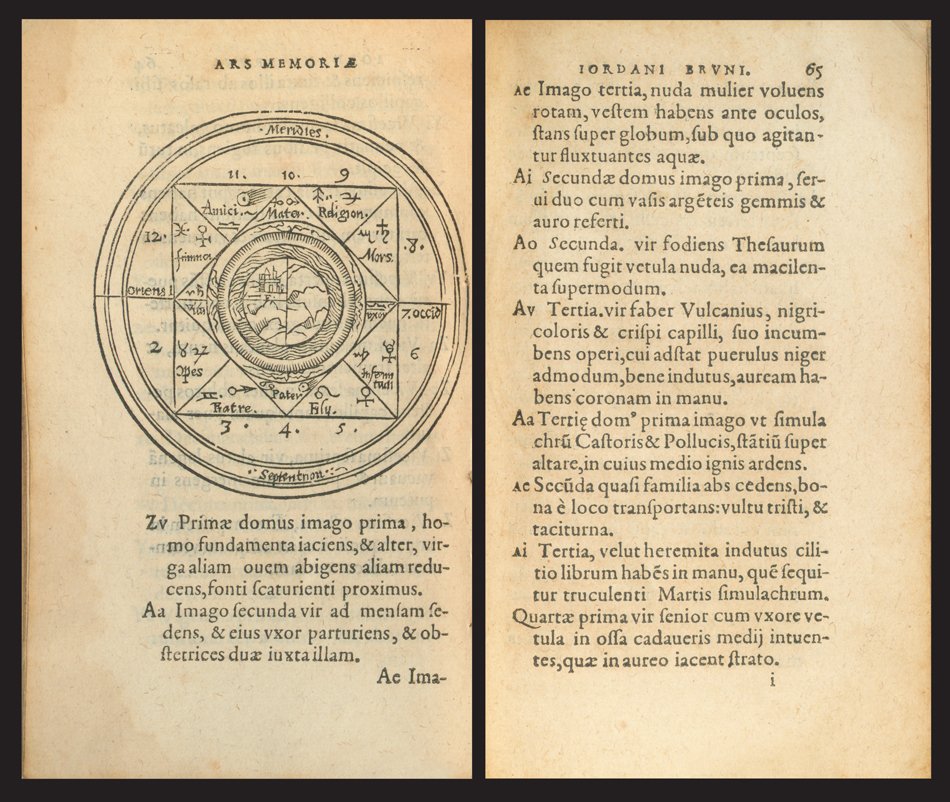

Giordano Bruno (1548-1600)

Parisiis: Apud Ægidium Gorbinum, 1582

Helen and Ruth Regenstein Collection of Rare Books

Former Dominican Giordano Bruno took pride in making contentious theological claims about magic. Bruno’s first publication De Umbris Idearum recounted memorization techniques apparently so effective they bordered on the supernatural. Here, Bruno divided the horoscope into twelve “houses,” an image of power invented to aid memorization. Bruno’s magical skills and penchant for insulting his patrons led to his condemnation by the Inquisition.

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499)

Venetijs: Ioannis Baptiste de Pederzanis, 1524

Rare Books Collection, Gift of Julius Rosenwald

Although well-loved by many, Marsilio Ficino feared his treatises could land him in trouble with the Church. In Platonica Theologia (written 1474, published 1482), Ficino emphasized that theologically touchy concepts were affirmed “insofar as they are approved by Christian theologians” and discussed as fun exercises, since “it is delightful to play…with the ancients” (XVIII.V.1), using these asides to discuss dubious subjects without fear of pushback.

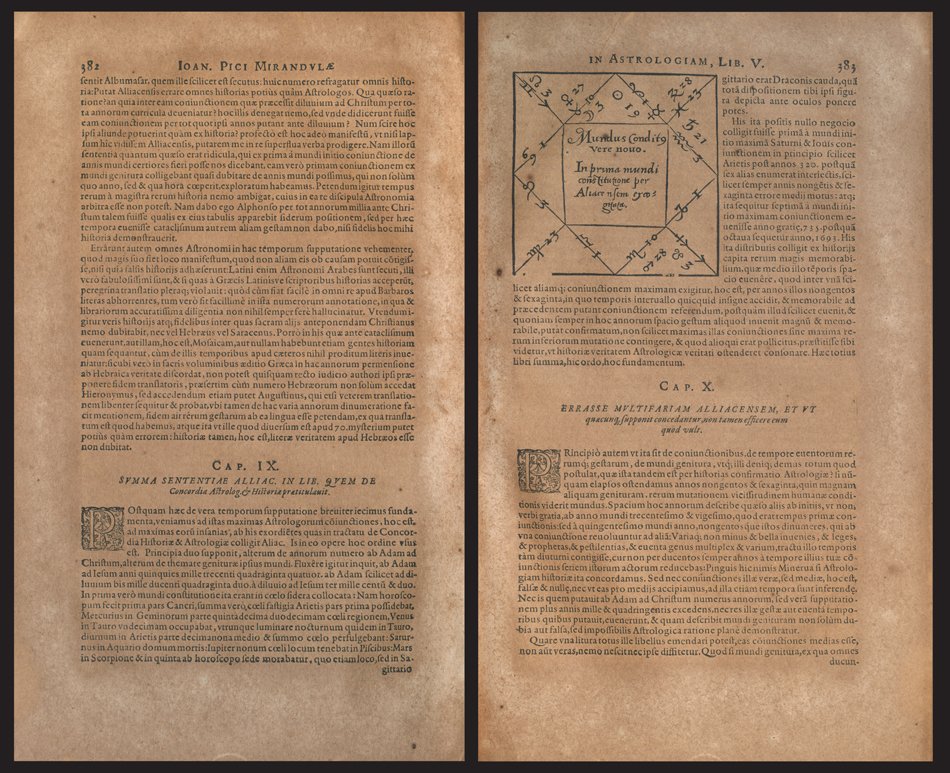

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494)

Venetiis: Apud Franciscum, 1569

Rare Books Collection, From the Library of Richard McKeon

Despite magic’s association with astrology, many Renaissance magicians did not wish to call themselves astrologers. Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola composed the Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatricem (1494), which criticized astrology fiercely for denying human free will by divining the future. The Disputationes may have been a critique of his teacher Ficino’s astrology and were certainly distancing divination from the proper practice of magic.