International Communism

Introduction

While the 1917 Revolution was confined to the Russian Empire, leaders such as V.I. Lenin anticipated that socialism would ultimately spread to the rest of the world. The Soviet Union was to set an example of a successful Communist state and to raise defenders for international worker’s rights. Many Soviet children’s books of the 1920s and 1930s reflect this concern, while others seek simply to educate children about cultures around the world.

Describing Nationalities

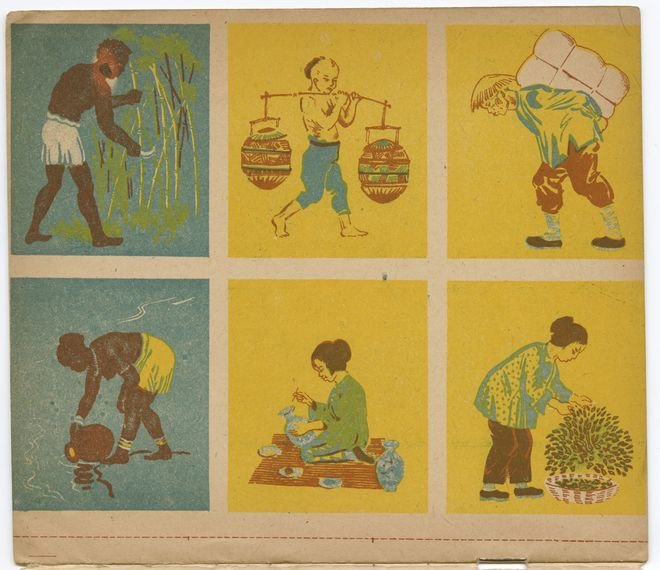

The motto “national in form, socialist in content” applied to people groups both within the USSR and around the world. Many children’s books purport to celebrate and describe the cultures of the various people groups. For example, N. P. Pospelova’s Deti narodnostei (Children of Nationalities) is a children’s matching game in book form. Each page consists of four pictures of boys and girls of various “nationalities.” The children are portrayed using stereotypical shorthand to make their national origin clear. The author instructs teachers to answer all their students’ questions about “where the nationalities live, what the adults of that nationality do, and how their children help them.” While the goal of this game is ostensibly descriptive, the attention to modes of production points to an overarching concern for the international working class.

Workers’ Children Around the World

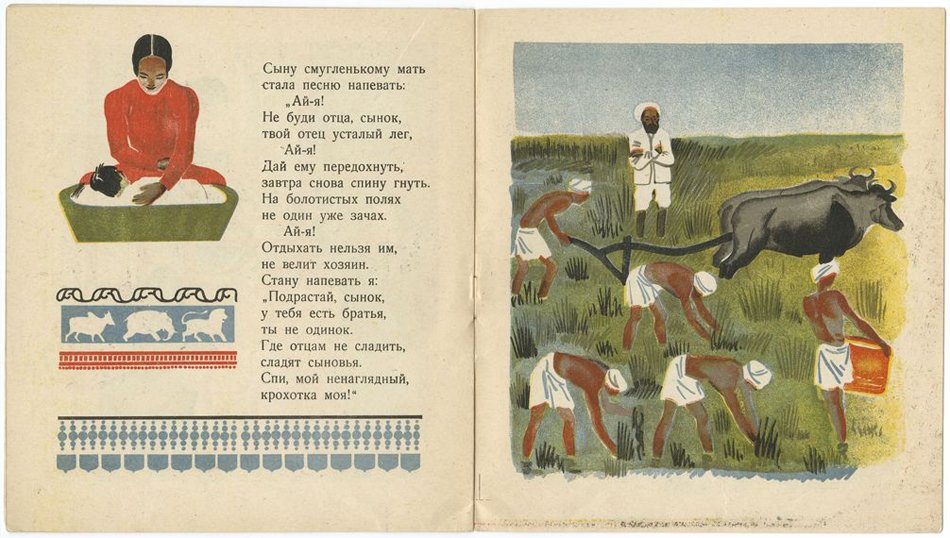

Many books present the concern for the international working class more explicitly. Bratishki (Little Brothers), by Agniia Barto, describes children from Russia, Africa, East Asia, and South Asia in terms of skin color, eye shape, caricatures of language, and the family’s work. The Indian child’s father works in the fields under the watchful eye of a harsh overseer; the East Asian boy’s mother works long hours in a textile factory. Only the Russian boy’s father works “for himself.” The book concludes with the Russian mother’s lullaby:

Don’t forget your brothers, away in a far-off land

Maybe, someday,

In fire and in smoke

You will be victorious with them!

Lullaby, lullaby.

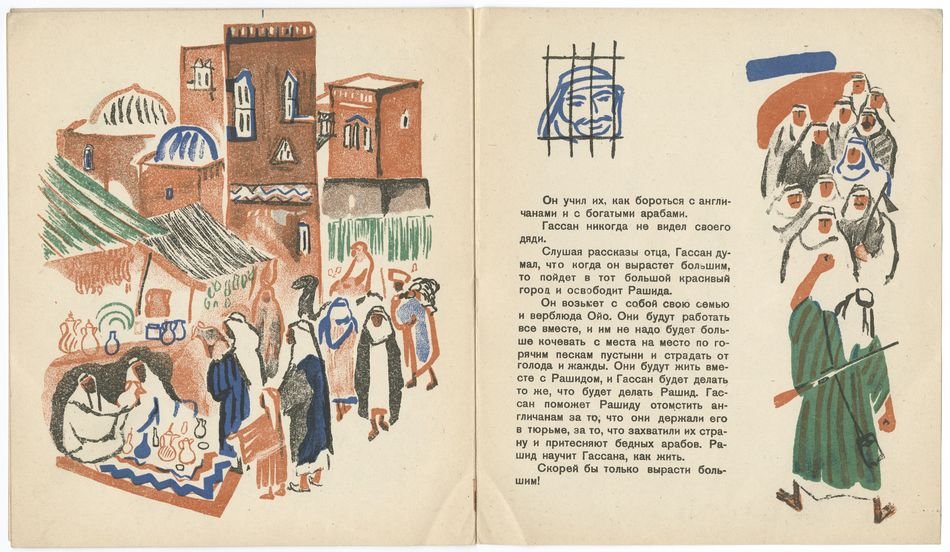

A. Gelina’s Gassan, arabskii mal’chik (Hassan, an Arab Boy) portrays the difficult life of a nomadic boy in British colonial Arabia. Rich merchants and well-fed English colonists live in the city, but their wealth is forbidden to Hassan’s poor family, which traverses the desert with camels in search of food and water. Hassan’s uncle Rashid has been imprisoned for leading an uprising against the English. Young Hassan dreams of someday liberating his uncle and his people from the oppression of the merchants and the colonials.

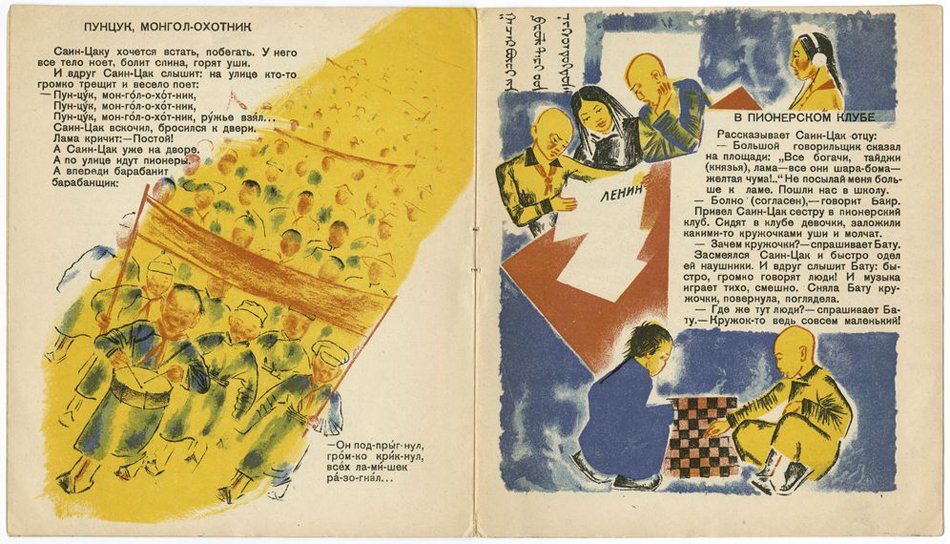

Mongolia (Mongolia) by Fedor Konstantinovich Fedotov tells the story of a little boy named Sain-Tsak and his sister Batu. Sain-Tsak suffers under the tutelage of a monk (lama) until he witnesses a parade of young communists, or Young Pioneers, in the city streets. Batu and Sain-Tsak begin going to school and attending the Young Pioneers club, where Sain-Tsak and Batu learn about Lenin. The narrator says that Sain-Tsak and his sister will help to found a new Mongolia, building “not yurts, but apartment buildings [doma], factories, and railroads.”

International Workers’ Movements

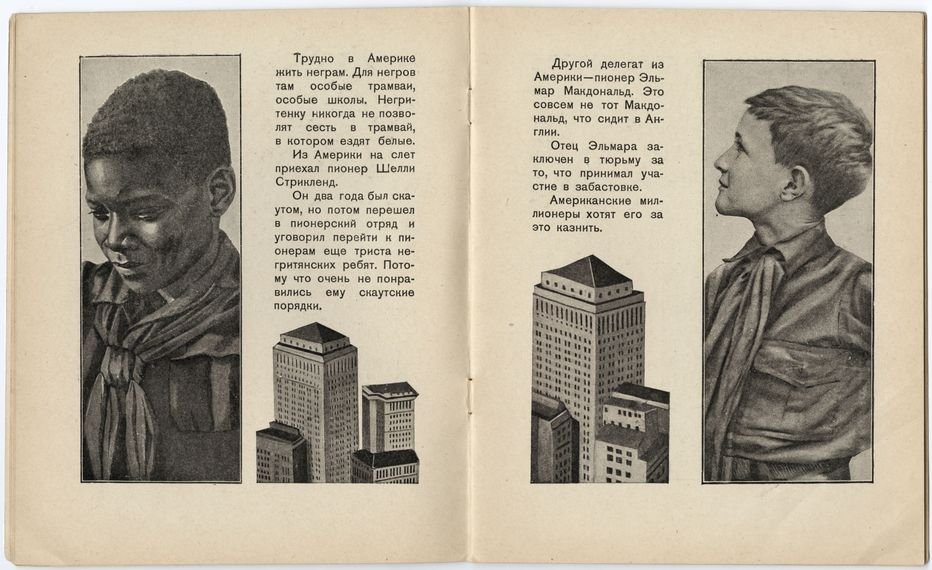

Oleg Shvartz’s Slet (The Convention) is a photo-essay about an international Young Pioneers conference held in Moscow. Children from places as far-flung as China, England, Switzerland, and the United States battle many obstacles to attend the conference. The Chinese children, for example, have to come secretly. Of the two children who come from the United States, one is Elmar MacDonald, the young son of an imprisoned Irish strike leader; the other is an African-American boy named Shelly Strickland who suffers under segregation, and who left the Boy Scouts to join the American branch of the Young Pioneers.

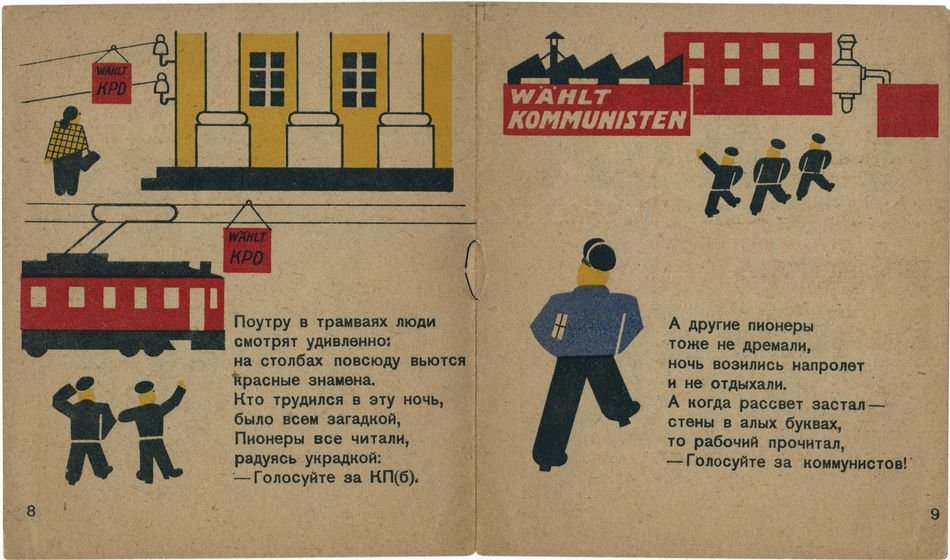

Some children’s books describe heroes of workers’ movements: Andre Marty (by N. Kupreianov, not pictured), for instance, tells the story of a leader of a mutiny on French battleships who later became a leader of the French Communist Party. A. D. Kuznetsova's Karl Liebknecht (not pictured) narrates the biography of one of the founders of the German Communist Party. Pioner i Politsiia (The Pioneer and the Police), which was written by a “young German worker” named G. Al’ner, tells a story about the twentieth-century German Pioneers movement. A disclaimer on the back cover of the book says that the book was published despite its “schematic and stylized” illustrations, which did not correspond to Soviet demands.

by Claire Roosien